Debt hysteria

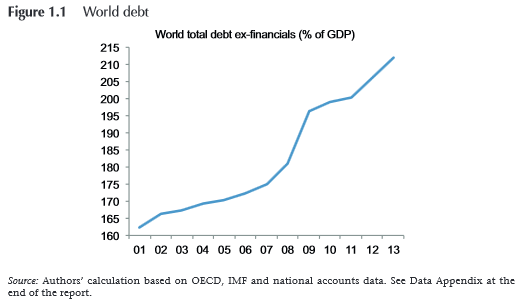

I have been reading the Geneva 16 report, which came out yesterday. It's scary stuff. If you thought the world was reducing its debt pile - forget it:

The debt is still growing, but the world's GDP growth is slowing. Indeed as aggregate debt figures are usually quoted versus GDP, the two are connected. The debt pile grows faster as growth slows, simply because the denominator is falling.

The report looks at total debt/GDP - not just sovereign debt. This is refreshing: unrelenting media focus on sovereign debt as the principal problem misses the fact that in many countries the bigger burden is PRIVATE debt. However, it makes the figures even worse. Global debt, it seems, is a terrible problem.

None of this will come as a surprise to anyone, except perhaps the news that the world as a whole is actually accumulating debt rather than deleveraging. The deleveraging efforts by developed countries are being more than offset by the increasing debt of emerging markets, particularly China.

But as I read the report, I found myself wondering why there was no discussion of the other side of all this. Who are the owners of all this debt?

There is a simple answer to this. Households and corporations own this debt. It is the savings of households and the uninvested profits of corporations. Since the financial crisis, developed-country governments also own some of this debt, via their central banks. And in emerging markets, where governments, corporations and households can be very closely related, exactly who owns the debt can be unclear.

The global debt glut described in this report, and the global saving glut described by Bernanke, are the same thing. The authors note that growth has been slowing in developed countries since 1980. Indeed it has - and during that time capital ownership and indebtedness have been increasing in tandem, as we might expect since they are opposite sides of the same coin. The report cites numerous analyses that show high debt levels - public AND private sector - tending to impede growth as resources that could have been turned to productive investment are spent on debt service. Secular stagnation is as much a consequence of over-indebtedness as it is of excess capital.

The owners of debt think they have saved prudently and accumulated safe financial assets to insure them against an uncertain future. They believe that their savings are PAST income, stored. Bonds and bank accounts are simply their own money in another form. How very dare anyone suggest that their hard-earned savings should be lost in order to relieve the debt burden on others? Let the profligate debtors sort out their own problems. Prudent savers must be protected from loss.

But debt assets are not stored past income. They are actually claims on the FUTURE income of other people. When you buy bonds, you are spending, not saving. Your money goes to someone else and you have no right to its return. In return, you receive a promise. In a simple vanilla bond, the promise has two parts:

The price of the bond is the value of that promise, and it depends on the trustworthiness of the borrower. If the borrower is regarded as trustworthy, the price is high. But if the borrower is regarded as untrustworthy - say they have recently failed to honour a payment promise - the price is low.

Similarly, bank accounts are not "your money, stored". They are a loan to the bank. You give the bank your money in return for a promise of future income (interest payments), and possibly other services such as safe storage and payments. You don't have any right to return of that money: what you have is a promise that if you ask for it back, the bank will honour your request if it can.

Risk of loss due to default is a intrinsic part of lending. When you lend money - whether by buying bonds, putting money in a bank account, or lending directly to someone - you accept the risk that the borrower will fail either to make the promised payments or return your money. Your judgement of someone's creditworthiness governs the amount you will charge them for this risk: the interest rate on an unsecured loan to someone with a good credit history is typically far lower than on a loan to someone with a recent history of payment default. A good credit history is a very valuable intangible asset for a borrower. Destruction of trustworthiness as a result of default amounts to a serious loss of net worth.

You may insure against risk of default by demanding that the borrower pledge some of their assets as surety: this of course what pawnbrokers do, but it is also the foundation of all property lending and most lending in financial markets. A mortgage is a loan on which the lender has the right to seize an associated asset (property) in the event of default. A repurchase agreement (repo) is a loan on which the lender has the right to seize a certain amount of securities in the event of default. Since the financial crisis, secured lending has become far more widespread due to loss of trust. The world runs on pawnbroking.

The problem with this, of course, is that the assets pledged as surety may fall in value, as we saw in the subprime crisis. When this happens, the risk of default may or may not rise, but the risk of losses in the event of default rises. Suddenly the loan or the bond is not worth as much. And insurance policies such as CDS aren't foolproof either: insurers can go bankrupt if there are too many claims, as AIG and the monoline insurers discovered. Nor is deposit insurance wholly trustworthy: Iceland legally defaulted on deposit insurance obligations to overseas customers of its banks. There is no such thing as a completely safe debt asset.

Nevertheless, the world's savings are largely held in the form of the world's debt, and people like to believe that their savings are safe. Because too high a debt burden increases the likelihood of default, many people - including the authors of the Geneva 16 report - think that governments should reduce sovereign debt. There are four principal ways of doing this:

For a government to run a persistent budget surplus requires that it takes in tax more than it spends. In the absence of a trade surplus, this means extracting money from the domestic private sector, which understandably does not want to give it up.* Running a sustained budget surplus when there is a trade deficit amounts to financial repression. But even if there is a trade surplus, a government surplus means lower saving for the private sector than it might desire. The Geneva 16 report points to substantial debt overhangs in the private sector. When the private sector is highly indebted, saving can take the form of paying off debt. If the government runs a surplus, therefore, it impedes deleveraging in the private sector, and may even force some sectors (typically the poor) to increase debt. Reducing the sovereign debt not only reduces saving in the private sector, it comes at the price of continued and possibly rising indebtedness. The report rightly notes that transferring debt from the private to the public sector, as the US has done, isn't deleveraging. But transferring it back again isn't deleveraging either. And as transferring it back again is likely only to be possible with extensive sovereign guarantees (the UK's Help to Buy, for example), whose debt is it really, anyway?

Reports such as this, that look on debt as a problem and ignore the associated savings, fail to address the real issue. The fact is that households, corporations and governments like to have savings and are terrified of loss. Writing down the debt in which people invest their savings means that people must lose their savings. THIS is the real "shock, horror". This is what people fear when they worry about a catastrophic debt default. This is what the world went to great lengths to prevent in 2008. The problem is not the debt, it is the savings.

If we really wish to reduce the global debt pile, we must either accept that the households, corporations and governments that currently own that debt must take losses, or find alternative investment vehicles. The problem, of course, is that potential replacements are either illiquid (property), risky (equities) or volatile (commodities).

I don't think that trying to find substitutes among existing asset classes in any way solves the problem of "too much debt". Debt is dysfunctional. It places debtors in a one-down position in relation to creditors and creates moral hazard for both - creditors because they can claim their due even at the price of severe hardship for the other, and debtors because they believe creditors will balk at enforcing the terms of the contract. This dilemma is centuries old: in The Merchant of Venice, Shylock's "pound of flesh" was his rightful due when Antonio defaulted on his loan, but enforcing that right would have killed Antonio and made Shylock a murderer. Shakespeare rightly lampooned such a destructive relationship, but four hundred years later nothing has fundamentally changed: we might not murder defaulters, but we certainly make their lives extremely difficult. We need a fundamentally different way of viewing the investments that households, corporations and governments make.

I think the world is inching its way towards a model that replaces most debt with equity. We have already seen debt for equity swaps in distressed banks. Perhaps we need debt for equity swaps for sovereigns, too. Why not replace USTs with shares in USA Inc.? Let's stop calling it "sovereign debt". It's share capital. It's our collective investment in our own futures.**

Debt for equity swaps are also possible for households that have both assets and debt - an over-mortgaged homeowner, for example. Though I wouldn't want to take this too far. Someone whose net worth is less than their debts cannot offer a debt for equity swap. They are insolvent, and their debt needs to be written off, not restructured. We do not want to see a return of debt peonage. But there are other shared-equity models that could replace current debt-based ones: imagine, for example, well-off elderly sponsoring the tertiary education of young people and mentoring them during their studies and in the early part of their careers. Or, for that matter, young people investing in the care of the elderly in return for a share in their housing wealth.

Clearly there are limits to the equity-savings model: there would still be a role for some debt, and some losses will have to be accepted. But equity is (pardon the pun) a far more equitable investment than debt, since issuers and investors are equally responsible for the success of the investment. Yes, an equity investment is ostensibly higher risk than lending: but haven't we yet learned that the safety of debt is an illusion?

Indeed, is it not time we stopped trying to buy the illusion of safety to comfort ourselves at the expense of others? There is a world of opportunity out there. Let's stop cowering in the dark, get out into the sunshine and sow the seeds of the next Golden Age.

Related reading:

Deleveraging, what deleveraging? - Geneva 16 (CEPR)

The deadly quest for safety

Government debt isn't what you think it is

On risk and safety

The other side of debt

* To show this, here is the familiar sectoral balances equation:

(S-I) = (G-T) + (X-M)

where S = private sector saving, I = private sector investment, G = government spending, T = tax revenues, X = exports and M = imports. S-I is usually positive because not all saving is invested in the private sector: the residual is private sector holdings of government debt and money ("net financial assets"). At the present time, the excess of S over I is considerable.

Let's assume for the moment that trade is balanced, i.e. X-M = 0. It is easy to see that if the government runs a surplus, i.e. G-T < 0, S-I must decrease. In other words, the private sector's overall saving must reduce. If X-M > 0, then clearly S-I may not actually reduce. However, even with a positive trade balance, the government's surplus means lower saving for the private sector than would have been the case with a deficit. Therefore it is fair to say that the government's surplus is confiscation of the private sector's actual or intended savings - i.e. financial repression.

** I have to caveat this proposal. Issuing share capital to replace debt is not a solution to the Eurozone crisis. Since sovereign share capital is really only a version of currency, members of the Eurozone do not have the capacity or the authority to issue shares to replace debt. But there is no federal-level institution that could or would do this either. The denial of the right of sovereigns to issue their own share capital is one of the most poisonous aspects of the Euro project.

The debt is still growing, but the world's GDP growth is slowing. Indeed as aggregate debt figures are usually quoted versus GDP, the two are connected. The debt pile grows faster as growth slows, simply because the denominator is falling.

The report looks at total debt/GDP - not just sovereign debt. This is refreshing: unrelenting media focus on sovereign debt as the principal problem misses the fact that in many countries the bigger burden is PRIVATE debt. However, it makes the figures even worse. Global debt, it seems, is a terrible problem.

None of this will come as a surprise to anyone, except perhaps the news that the world as a whole is actually accumulating debt rather than deleveraging. The deleveraging efforts by developed countries are being more than offset by the increasing debt of emerging markets, particularly China.

But as I read the report, I found myself wondering why there was no discussion of the other side of all this. Who are the owners of all this debt?

There is a simple answer to this. Households and corporations own this debt. It is the savings of households and the uninvested profits of corporations. Since the financial crisis, developed-country governments also own some of this debt, via their central banks. And in emerging markets, where governments, corporations and households can be very closely related, exactly who owns the debt can be unclear.

The global debt glut described in this report, and the global saving glut described by Bernanke, are the same thing. The authors note that growth has been slowing in developed countries since 1980. Indeed it has - and during that time capital ownership and indebtedness have been increasing in tandem, as we might expect since they are opposite sides of the same coin. The report cites numerous analyses that show high debt levels - public AND private sector - tending to impede growth as resources that could have been turned to productive investment are spent on debt service. Secular stagnation is as much a consequence of over-indebtedness as it is of excess capital.

The owners of debt think they have saved prudently and accumulated safe financial assets to insure them against an uncertain future. They believe that their savings are PAST income, stored. Bonds and bank accounts are simply their own money in another form. How very dare anyone suggest that their hard-earned savings should be lost in order to relieve the debt burden on others? Let the profligate debtors sort out their own problems. Prudent savers must be protected from loss.

But debt assets are not stored past income. They are actually claims on the FUTURE income of other people. When you buy bonds, you are spending, not saving. Your money goes to someone else and you have no right to its return. In return, you receive a promise. In a simple vanilla bond, the promise has two parts:

- the promise that you will at some point in the future recover a nominal sum of money equal to the amount that you paid for the bond (note that this is not protected against inflation)

- the promise of a stream of coupon payments that may or may not include compensation for expected inflation

The price of the bond is the value of that promise, and it depends on the trustworthiness of the borrower. If the borrower is regarded as trustworthy, the price is high. But if the borrower is regarded as untrustworthy - say they have recently failed to honour a payment promise - the price is low.

Similarly, bank accounts are not "your money, stored". They are a loan to the bank. You give the bank your money in return for a promise of future income (interest payments), and possibly other services such as safe storage and payments. You don't have any right to return of that money: what you have is a promise that if you ask for it back, the bank will honour your request if it can.

Risk of loss due to default is a intrinsic part of lending. When you lend money - whether by buying bonds, putting money in a bank account, or lending directly to someone - you accept the risk that the borrower will fail either to make the promised payments or return your money. Your judgement of someone's creditworthiness governs the amount you will charge them for this risk: the interest rate on an unsecured loan to someone with a good credit history is typically far lower than on a loan to someone with a recent history of payment default. A good credit history is a very valuable intangible asset for a borrower. Destruction of trustworthiness as a result of default amounts to a serious loss of net worth.

You may insure against risk of default by demanding that the borrower pledge some of their assets as surety: this of course what pawnbrokers do, but it is also the foundation of all property lending and most lending in financial markets. A mortgage is a loan on which the lender has the right to seize an associated asset (property) in the event of default. A repurchase agreement (repo) is a loan on which the lender has the right to seize a certain amount of securities in the event of default. Since the financial crisis, secured lending has become far more widespread due to loss of trust. The world runs on pawnbroking.

The problem with this, of course, is that the assets pledged as surety may fall in value, as we saw in the subprime crisis. When this happens, the risk of default may or may not rise, but the risk of losses in the event of default rises. Suddenly the loan or the bond is not worth as much. And insurance policies such as CDS aren't foolproof either: insurers can go bankrupt if there are too many claims, as AIG and the monoline insurers discovered. Nor is deposit insurance wholly trustworthy: Iceland legally defaulted on deposit insurance obligations to overseas customers of its banks. There is no such thing as a completely safe debt asset.

Nevertheless, the world's savings are largely held in the form of the world's debt, and people like to believe that their savings are safe. Because too high a debt burden increases the likelihood of default, many people - including the authors of the Geneva 16 report - think that governments should reduce sovereign debt. There are four principal ways of doing this:

- by running persistent budget surpluses.

- by reducing the real value of the debt through inflation

- by reducing the debt/GDP ratio through higher growth.

- by outright confiscation of savings (financial repression)

For a government to run a persistent budget surplus requires that it takes in tax more than it spends. In the absence of a trade surplus, this means extracting money from the domestic private sector, which understandably does not want to give it up.* Running a sustained budget surplus when there is a trade deficit amounts to financial repression. But even if there is a trade surplus, a government surplus means lower saving for the private sector than it might desire. The Geneva 16 report points to substantial debt overhangs in the private sector. When the private sector is highly indebted, saving can take the form of paying off debt. If the government runs a surplus, therefore, it impedes deleveraging in the private sector, and may even force some sectors (typically the poor) to increase debt. Reducing the sovereign debt not only reduces saving in the private sector, it comes at the price of continued and possibly rising indebtedness. The report rightly notes that transferring debt from the private to the public sector, as the US has done, isn't deleveraging. But transferring it back again isn't deleveraging either. And as transferring it back again is likely only to be possible with extensive sovereign guarantees (the UK's Help to Buy, for example), whose debt is it really, anyway?

Reports such as this, that look on debt as a problem and ignore the associated savings, fail to address the real issue. The fact is that households, corporations and governments like to have savings and are terrified of loss. Writing down the debt in which people invest their savings means that people must lose their savings. THIS is the real "shock, horror". This is what people fear when they worry about a catastrophic debt default. This is what the world went to great lengths to prevent in 2008. The problem is not the debt, it is the savings.

If we really wish to reduce the global debt pile, we must either accept that the households, corporations and governments that currently own that debt must take losses, or find alternative investment vehicles. The problem, of course, is that potential replacements are either illiquid (property), risky (equities) or volatile (commodities).

I don't think that trying to find substitutes among existing asset classes in any way solves the problem of "too much debt". Debt is dysfunctional. It places debtors in a one-down position in relation to creditors and creates moral hazard for both - creditors because they can claim their due even at the price of severe hardship for the other, and debtors because they believe creditors will balk at enforcing the terms of the contract. This dilemma is centuries old: in The Merchant of Venice, Shylock's "pound of flesh" was his rightful due when Antonio defaulted on his loan, but enforcing that right would have killed Antonio and made Shylock a murderer. Shakespeare rightly lampooned such a destructive relationship, but four hundred years later nothing has fundamentally changed: we might not murder defaulters, but we certainly make their lives extremely difficult. We need a fundamentally different way of viewing the investments that households, corporations and governments make.

I think the world is inching its way towards a model that replaces most debt with equity. We have already seen debt for equity swaps in distressed banks. Perhaps we need debt for equity swaps for sovereigns, too. Why not replace USTs with shares in USA Inc.? Let's stop calling it "sovereign debt". It's share capital. It's our collective investment in our own futures.**

Debt for equity swaps are also possible for households that have both assets and debt - an over-mortgaged homeowner, for example. Though I wouldn't want to take this too far. Someone whose net worth is less than their debts cannot offer a debt for equity swap. They are insolvent, and their debt needs to be written off, not restructured. We do not want to see a return of debt peonage. But there are other shared-equity models that could replace current debt-based ones: imagine, for example, well-off elderly sponsoring the tertiary education of young people and mentoring them during their studies and in the early part of their careers. Or, for that matter, young people investing in the care of the elderly in return for a share in their housing wealth.

Clearly there are limits to the equity-savings model: there would still be a role for some debt, and some losses will have to be accepted. But equity is (pardon the pun) a far more equitable investment than debt, since issuers and investors are equally responsible for the success of the investment. Yes, an equity investment is ostensibly higher risk than lending: but haven't we yet learned that the safety of debt is an illusion?

Indeed, is it not time we stopped trying to buy the illusion of safety to comfort ourselves at the expense of others? There is a world of opportunity out there. Let's stop cowering in the dark, get out into the sunshine and sow the seeds of the next Golden Age.

Related reading:

Deleveraging, what deleveraging? - Geneva 16 (CEPR)

The deadly quest for safety

Government debt isn't what you think it is

On risk and safety

The other side of debt

* To show this, here is the familiar sectoral balances equation:

(S-I) = (G-T) + (X-M)

where S = private sector saving, I = private sector investment, G = government spending, T = tax revenues, X = exports and M = imports. S-I is usually positive because not all saving is invested in the private sector: the residual is private sector holdings of government debt and money ("net financial assets"). At the present time, the excess of S over I is considerable.

Let's assume for the moment that trade is balanced, i.e. X-M = 0. It is easy to see that if the government runs a surplus, i.e. G-T < 0, S-I must decrease. In other words, the private sector's overall saving must reduce. If X-M > 0, then clearly S-I may not actually reduce. However, even with a positive trade balance, the government's surplus means lower saving for the private sector than would have been the case with a deficit. Therefore it is fair to say that the government's surplus is confiscation of the private sector's actual or intended savings - i.e. financial repression.

** I have to caveat this proposal. Issuing share capital to replace debt is not a solution to the Eurozone crisis. Since sovereign share capital is really only a version of currency, members of the Eurozone do not have the capacity or the authority to issue shares to replace debt. But there is no federal-level institution that could or would do this either. The denial of the right of sovereigns to issue their own share capital is one of the most poisonous aspects of the Euro project.

Excellent article Frances.

ReplyDeleteCan I suggest an extension to it? Which is to ask, what are savings for?

Not so long ago, most people had next to no savings. Yet now it seems to be a coming "right" that not only should you be able to amass savings, but they should be passed on to your children almost untaxed, and to that we can now add property in the form of the family home as well.

Savings were originally "for a rainy day" - as insurance. Yet you could imagine that, if we lived in a country with low rents, a satisfactory basic income and a free health service, such insurance would be unnecessary. We're not a massive distance away from that scenario. So what exactly are we (or should we be) saving to insure ourselves against ...?

I do agree. We have become obsessive about private savings. It's all part of the economic morality play I keep moaning about. Saving = good, spending = bad. Debtors = profligate, creditors = prudent. It's complete nonsense, but pervasive - and it is driving a lot of policy at the moment, particularly in the Eurozone but also in other places.

DeleteThe obsession with private savings is really quite toxic. Because of their distributional shortcomings, private savings cannot possibly replace a decent public sector safety net. But because those with savings are terrified of losing them, we are prepared to cut back the safety net for those too poor to save in order to calm the fears of those who have savings. It is fundamentally illogical and socially divisive.

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteAs the last part of this post argued that we need far more equity investment and far less debt, of course I agree that savings do not have to lead to debt. That is not what the statement you have quoted means. Government over-taxing in order to reduce its own debt reduces private sector saving, impedes private sector deleveraging and may force some sectors to releverage. If this happens (which is more likely if there is a trade deficit) then the TOTAL debt burden does not decrease - it simply transfers from the public sector to the private sector. I'd suggest you have a look at the sectoral balance analysis in the footnote as it explains this.

DeleteExcellent comment. Thank you.

DeleteIgnore the comment... but you cannot possibly conclude that savings is bad and go on to argue that we should be investing more in equity. How do you take up an equity position without savings?

ReplyDeleteWhere did I conclude that savings were bad? In this post I am simply dealing with the reality that the world's debt pile is entirely made up of people's savings. If they are not prepared to transfer to non-debt savings vehicles, reducing the debt pile will mean loss of savings.

DeleteThank you Frances. It has driven me crazy for some time that politicians and the media finger-wag at borrowers without recognizing that it is fueled by those with more money than they are willing to spend.

ReplyDeleteForest fires can be essential to keep the natural ecosystem in balance, and human intervention to prevent them can actually be harmful. I increasingly wonder if government intervention in the credit crisis was analogous to interfering with a natural forest fire. Has the rescue of wealth that "should have died" created "zombie money" that ballooned the savings glut? Does the explosion in wealth inequality since the crisis imply that losses - had they been allowed to happen - would have been borne overwhelmingly by those who could afford them? And if losses had been recognized in an orderly fashion rather than following a policy of "extend & pretend", would the world be in better shape today?

In addition to the nonsense involved in praising saving while criticising debt, another related nonsense is the fact that the people who criticise debt are often the same people who defend the existing or fractional reserve banking, which by its very nature has to be subsidised or backed by taxpayers: witness the several trillions of public money recently used to rescue it. I.e. criticising debt while advocating subsidising the debt creation process is a self-contradiction.

ReplyDelete"The problem is not the debt, it is the savings."

ReplyDeleteYou are right that debt and savings are just two sides of the same coin and you can't understand what's going on with one without looking at the other.

The reason people worry about debt more is simply because that's where the tensions are. In theory, for any given entity there are no caps on their potential wealth to income ratio. But there are limits on debt to income ratios (because of credit considerations) and it's when we get close to these that people start worrying about fragility.

The Geneva 16 report sensibly looks at debt service to income ratios - i.e. affordability. The size of the debt pile itself is not really the issue - it's the cost of servicing it that is the problem. This is why Geneva 16 say interest rates will stay very low for a very long time. When debt to income ratios are very large, debt service costs have to be low. Raising interest rates is just too dangerous. But I would argue that with near-zero interest rates for the foreseeable future, lenders have little to lose by converting debt to equity. They aren't making any money and the debt is never going to be paid back.

DeleteDo they look at debt service to GDP ratios, compare them over time and project them into the future? That would truly tell people something about "affordability". Comparing debt service to Income ratios is just a measuring of a government's tax policy, which could be unrelated to the underlying health of the economy.

DeleteSo debt service to income ratio still shadows the truth a bit.

(I've posted this same complaint before)

Reducing the debt pile does not require savers to loose out, debt can be repaid by the normal process of commerce.

ReplyDeleteDinero,

DeleteFirstly, if there is less debt then there will be less savings. What savings there are might be more valuable, however.

Secondly, I think it is by now crystal clear that the world's debt pile cannot be paid off through the normal process of commerce.

Oh, and before you say it - yes, savings could move to non-debt asset classes. But that would imply a massive expansion of those classes, which means that in effect debt would have been converted to something else - money, equity......Reducing debt means reducing savings IF EVERYTHING ELSE REMAINS UNCHANGED.

DeleteWhen you say everything else remains unchanged , do you mean the same number of transactions.

DeleteCommerce. Goods, services , taxes and rents. the normal route is that the person with the debt sells something to the person with the savings, and so the savings are exchanged for something else including consumption. If savers did spend more then the debtor has the income to repay the debt, the savings. If the savers do not spend then the debt and savings stay as an open set of accounts. Why do you say that cant happen, what are the figures. 215% of GDP another example is people with mortgages have 400% times their income, and the global debtors may keep changing. If there was no debt their would be no money and so what do you think the optimal level is bearing in mind as you point out the denominator effect.

Dinero,

DeleteAs I understand it most of the debt is owed to commercial banks, which means the money was created by the banks when the loans were issued and is destroyed on repayment of the loans.

If the money that's destroyed does not come from savings it must be removed from the flow that's used for commerce, which means less is available for buying and selling.

We can't simultaneously maintain savings, pay off debt, and have a thriving economy. Any two are possible; not all three together.

Increase wages. Debt service ratios reduce.

ReplyDeleteThere is a sophistry in this essay, that as a last resort, sovereign debt can be swapped for equity - as if a country were a corporation, which it is clearly not. The problem seems to arise from your premise that debt and savings are merely different sides of the same coin. Our fractional banking system that allows deposits to multiply and indeed the basic function of a central bank to expand the monetary base out of thin air ought to be a clue that this one to one relationship between savings and debt is a fantasy.

ReplyDeleteTo say that bank depositors are subject to vagaries of lending is baloney. Maybe that was true before 1933. Now, we know that nominal money is good, thanks to FDIC which exempts us form this concern, which by the way changes the basic contract between borrower and lender. We the people are guaranteeing our own deposits (up to $250K) period, clearly peeling one level of risk that you claim to exist, away.

And if bonds were indeed converted to equity, how then would you deal with the trillions of good faith promises of life insurance, pensions, and every other delayed benefit that depends on the interest of the assets in the plan to survive? An outraged public would rightly engage in a revolt against such a scheme.

And what of foreign lenders. Are they entitled to a piece of soverign equity on the same basis as domestic lenders. Just wait for the lawyers to feast on that dillema.

What you are advocating is sovereign default, dressed in sheep's clothing. It won’t work

"The report cites numerous analyses that show high debt levels - public AND private sector - tending to impede growth as resources that could have been turned to productive investment are spent on debt service. Secular stagnation is as much a consequence of over-indebtedness as it is of excess capital."

ReplyDeleteWhat do you say to the people who say debt does not matter because:

1) $ borrowed = $ lent

2) for every borrower there is a lender

3) debt is an asset to one entity and a liability to another

4) debt does not matter because "we" owe it to ourselves

All of those people are in effect saying that gross amounts are unimportant - all that matters is the net effect. As long as debt and savings roughly balance, there is no risk, however large the gross amounts become. But if there is one thing we should have learned from the financial crisis, it is that gross amounts DO matter.

DeleteAs debt levels rise, debt service crowds out other activity and eventually becomes unaffordable, forcing some form of default - this is actually far more likely with private debt than sovereign, since private sector actors lack the ability to fund themselves as sovereigns can. The financial crisis was a sudden widespread private debt default which was partially offset by sovereign monetization of private sector debt: the result, as the Geneva 16 report points out, is highly-indebted sovereigns throughout the developed world and at present no realistic plans for reducing their indebtedness.

But over-capitalisation is also a problem. As the level of capital rises, it is harder to find productive uses for it, which drives down the return on capital. This causes growth to slow and asset bubbles to emerge as investors chase both yield and safety. I haven't discussed this in this post, but debt and savings increase in tandem because both arise from the same cause - credit creation by financial institutions, both regulated and unregulated. There has been a huge rise in credit creation over the last thirty years, and it is still increasing, as the chart above shows. Consequently the world is flooded with capital that it doesn't know what to do with.

That doesn't mean there aren't productive investment opportunities (I think there are) but they are either regarded as too high risk or they don't give the returns investors have come to expect. Or - since investors are creatures of habit - they haven't thought of them. I think this last effect is very important and never discussed.

“All of those people are in effect saying that gross amounts are unimportant - all that matters is the net effect. As long as debt and savings roughly balance, there is no risk, however large the gross amounts become. But if there is one thing we should have learned from the financial crisis, it is that gross amounts DO matter.”

DeleteExactly. Here is how I think 1 and 2 should be replied to. $ borrowed does not have to equal $ saved. For every borrower, there may not be a saver. When a bank creates demand deposits “out of thin air”, is that considered savings? I’m assuming it is not. I’m also assuming the capital requirement is less than 100%.

“But over-capitalisation is also a problem. As the level of capital rises, it is harder to find productive uses for it, which drives down the return on capital.”

Is that because real AD is not unlimited, contrary to the most common definition of economics (unlimited wants/needs and limited resources)?

“This causes growth to slow and asset bubbles to emerge as investors chase both yield and safety. I haven't discussed this in this post, but debt and savings increase in tandem because both arise from the same cause - credit creation by financial institutions, both regulated and unregulated. There has been a huge rise in credit creation over the last thirty years, and it is still increasing, as the chart above shows.”

If done thru a bank or bank-like entity, has this been increasing the amount of MOA/MOE?

“That doesn't mean there aren't productive investment opportunities (I think there are) but they are either regarded as too high risk or they don't give the returns investors have come to expect. Or - since investors are creatures of habit - they haven't thought of them. I think this last effect is very important and never discussed.”

I’m not so sure about the productive investment opportunities. What if there are very, very few of them?

1) When banks create demand deposits out of thin air, those become part of overall savings in the economy. When the loan is spent, the savings simply move to a different person. Equity (shareholders' funds, retained earnings) is the bank's OWN savings -I included corporate savings, remember. So for every borrower there IS a saver. Amounts borrowed must be matched by amounts saved. However, not every saver has a borrower: it depends how they invest their funds. Stuffed mattresses, for example, have no associated debt, unless you count currency as debt (which is questionable in a fiat currency system). So debt=savings, but savings does not = debt.

Delete2) Limited supply and unlimited demand is far too simplistic a view of economics. Say's Law cannot be shown to hold in a world where there are nominal rigidities.

I'm not going to use terms like MOA/MOE. They are mostly used by people who want to pretend that what everyone uses to pay for their shopping isn't money. I'm not going to play that game. If it is used by ordinary people for everyday transactions, it is money - whoever creates it. A rise in bank lending is paralleled by an increase in the money supply and a rise in savings (note the plural - I am not saying that bank lending increases saving activity).

Why would you assume that there are very few productive investment opportunities? There are always things that need doing from a social point of view. The problem is the risk versus return profile of those opportunities.

“When banks create demand deposits out of thin air, those become part of overall savings in the economy. When the loan is spent, the savings simply move to a different person. Equity (shareholders' funds, retained earnings) is the bank's OWN savings”

DeleteI don’t get that one at all. Why would demand deposits created out of thin air be considered savings? I’m thinking savings (S) = income (Y) minus consumption (C). I believe equity is the bank’s own savings. I believe demand deposits are the bank’s liabilities, not equity. I’m thinking I’m asking are demand deposits created out of thin air considered income.

For example, I save $1,000 in currency to start a new bank. The reserve requirement is 10%, and the capital requirement is 10%. That scenario allows $10,000 in demand deposits and $10,000 in loans to be created. The $10,000 in demand deposits get spent. $1,000 in currency was saved, and $10,000 in demand deposits was dissaved.

Assets = $1,000 in currency and $10,000 in loans

Liabilities = $10,000 in demand deposits

Equity = $1,000

There is a $9,000 difference there.

“Limited supply and unlimited demand is far too simplistic a view of economics.”

DeleteEspecially if demand is not unlimited?

“I'm not going to use terms like MOA/MOE. They are mostly used by people who want to pretend that what everyone uses to pay for their shopping isn't money. I'm not going to play that game. If it is used by ordinary people for everyday transactions, it is money - whoever creates it.”

I’d say money is MOA. When the MOA has a fixed rate to something else, there is a dual MOA. That makes currency plus demand deposits the MOA, not monetary base. It also happens to be MOE so they have velocity.

“Why would you assume that there are very few productive investment opportunities? There are always things that need doing from a social point of view. The problem is the risk versus return profile of those opportunities.”

What if there is a social return but not a “money” return?

You are confusing stocks and flows. In the identity S=Y-C (I use Y for income), S is saving (flow), not savingS (stock).

DeleteDemand deposits are the savings of bank customers. When a loan is created, the bank creates a new demand deposit for the amount of the loan, increasing the stock of savings of that customer (while simultaneously also increasing their debt, of course - as I said, gross amounts DO matter). When the customer draws the loan, the deposit transfers to the demand deposit of the recipient, increasing their stock of savings. The borrower is left with the debt but not the savings, while the bank is left with a liability hole that it must fill - this is where bank funding becomes important. This is how fractional reserve lending works. The money supply and the stock of savings increase in tandem with the stock of debt, but there is no new saving (flow). Note also that reserve requirements are irrelevant. Many countries (including mine) don't have them.

I really don't care whether you call money MOA, MOE or SOV. Actually it is all three.

If the return to the private investor is insufficient to attract them but the investment is socially desirable, then the appropriate investor is government. But that is a very different matter from my point, which is that the excess of capital over productive uses for it drives down return on capital to zero.

Is the $9,000 part correct?

DeleteAssume the $10,000 is spent for consumption. I consumed $1,000 less, and the borrowers consumed $10,000 more?

Now move the capital requirement to 100%. I consumed $1,000 less, and the borrowers consumed $1,000 more?

Now put a 100% capital requirement on the central bank itself.

Money doesn't disappear when you spend it on consumption. It simply moves somewhere else. The money you spend becomes someone else's savings (I am assuming that "savings" are all idle money balances, i.e. money that has not been spent "yet"). However you look at it, in your model both debt and savings have increased by $9,000.

DeleteSince deposits (which are bank debt) are created when banks lend, a strictly enforced 100% capital requirement would prevent the bank from lending at all. It could still act as a pure intermediary, only lending out cash it has already saved itself (your $1,000), but that isn't banking. Neither the money supply nor the stock of savings increase when pure intermediaries lend, and in this post I did not suggest that they did.

In a fiat money system central banks effectively have 100% capital requirements. Currency and bank reserves are equity, not debt.

“However you look at it, in your model both debt and savings have increased by $9,000.”

DeleteBut not saving (flow), right? For example, if the capital requirement went to 100%, then saving (flow) would need to increase by $9,000?

What is your definition of monetary policy?

Would raising the capital requirement to 20% so that only $5,000 in demand deposits and $5,000 in loans could be created be considered tightening monetary policy?

“In a fiat money system central banks effectively have 100% capital requirements.”

Don’t central banks have a lot more assets than capital? I’m thinking a 100% capital requirement means capital and assets have to be the same. That means saving (flow and see above) would need to increase?

“Currency and (central, my add) bank reserves are equity, not debt.”

Why aren’t central bank reserves considered the demand deposits of the central bank and therefore debt?

1) I think I've made it clear that in fractional reserve lending the stock of savings increases but the flow of saving does not necessarily change. If the lending was done by a pure intermediary, the same volume of lending would require an increase in saving (flow) of $9000 prior to lending.

DeleteChanging capital requirements is macroprudential regulation, not monetary policy. So no, raising capital requirements would not be considered tightening monetary policy. Nor would raising capital requirements necessarily reduce the volume of lending. Banks could raise more capital from the markets or from their shareholders.

2) The liability side of central banks' balance sheets is the monetary base, which is not "owed" to anybody - in a fiat money system it is only redeemable as more of itself. It is therefore more like equity than debt. Central banks therefore in effect have 100% capital.

"Why aren't central bank reserves considered the demand deposits of the central bank"....you can't possibly mean that. Reserves at the central bank are the demand deposits of commercial banks, but see my comment about the monetary base not being "owed" to anyone. Central banks are something of a special case and it really isn't helpful to start talking of them as having debt in any normal sense.

“Changing capital requirements is macroprudential regulation, not monetary policy. So no, raising capital requirements would not be considered tightening monetary policy. Nor would raising capital requirements necessarily reduce the volume of lending. Banks could raise more capital from the markets or from their shareholders.”

DeleteWon’t that lower returns? Won’t that dilute existing shares?

What if the banks refuse, and the fed needs more M (demand deposits) to keep either NGDP or price inflation “on target”?

“2) The liability side of central banks' balance sheets is the monetary base, which is not "owed" to anybody - in a fiat money system it is only redeemable as more of itself. It is therefore more like equity than debt. Central banks therefore in effect have 100% capital.”

I don’t believe redeemable and owed have to do with a 100% capital requirement. See our discussion above. It is about saving (the flow of saving) being greater than or equal to dissaving (I assume the flow of dissaving). It seems to me redeemable and owed have to do with liquidity/illiquidity and insolvency.

"Why aren't central bank reserves considered the demand deposits of the central bank"....you can't possibly mean that. Reserves at the central bank are the demand deposits of commercial banks, but see my comment about the monetary base not being "owed" to anyone. Central banks are something of a special case and it really isn't helpful to start talking of them as having debt in any normal sense.”

Why aren't central bank reserves considered the demand deposits of the central bank (as in liabilities of the central bank and assets to the commercial banks)? Does that sound better? I’m thinking the central bank has demand deposits that are its liability and the commercial banks have demand deposits that are their liabilities. They have different “rules” applied to them.

I’m trying to convince people that currency should actually be another entity’s liability. Let me try it this way. Before the fed was created, currency was a liability of what entity?

1). Read "The Bankers' New Clothes" by Admati & Hellwig for an extensive discussion of capital raising by banks. Reducing return on equity is not necessarily a bad thing.

DeleteThe central bank's monetary policy is not dependent on bank lending. There are ways of increasing M even if banks refuse to lend.

2) No, it is absolutely about redeemable and owed. Equity is not "owed" to anyone. Nor is the monetary base. It is therefore much more like equity than debt.

It is not remotely sensible to talk about "insolvency" of a currency-issuing central bank with a credible government behind it. Insolvency of a central bank implies insolvency of the government itself.

3) Currency is not a liability of the public sector. It is a share in the public sector. You seem unclear about the difference between liability and equity. And you also seem to want to talk about both the currency and the central bank as if they have no relationship with government. In a fiat currency system the central bank is simply an arm of government and the currency is an expression of the government's sovereignty. If the sovereignty fails (traumatic regime collapse, for example - e.g. after the fall of the Soviet Union) fiat currency is liable to be rejected (hyperinflation). As long as the government is credible, neither the currency nor the central bank which issues it can fail.

Let's work on the capital requirement.

DeleteI hope we agree that with a 100% capital requirement commercial banks can’t increase “money”.

If the capital requirement is 100% for the central bank, doesn’t the same idea apply?

Onto the next idea.

Assume the capital requirement is 10% for the commercial banks and no deposit insurance.

Assets = 100. Liabilities (demand deposits) = 90. Equity = 10.

Assets drop to 81. What most likely happens?

Assume the central bank does all of the loans and there is only currency. Its capital requirement is 10%.

Assets = 100. Liabilities (currency) = 90. Equity = 10.

Assets drop to 81. What most likely happens?

A point on trustworthiness, the term may be somewhat misused here: someone trustworthy can engage in a risky make-or-break project, e.g. single-issue scientific research. If they disclose the risks to their creditors appropriately, the project can fail (to pay off) without any breach of trust.

ReplyDelete(and +1 on @crf's point)

Not sure swapping debt for equity helps much, what use is owning half the housing in Madrid to a big German bank say. How is that different from owning mortgages when it comes to economic crash time.

ReplyDeleteThe essential problem remains - accumulation of debt. Taking on debt to build a car factory seems OK, in a few years the debt is paid off with interest and cars (aka monies) are produced. The (good) accumulation of debt implies an ever increasing number of new investments followed by a larger number of new revenue streams. This would imply an ever increasing GDP number which does not seem to be happening. So why the debt without the GDP? Perhaps the economic equations need an extra (but embarrassing) factor Z standing for destroyed value - waste and failed projects.. For the difficulty is that without some way of harmlessly reducing Z or writing it off (without moral hazard) then debt will increase evermore. Perhaps we need to resurrect Shylock's punishment and see Finance Ministers and bankers led away in chains whenever their Z numbers increase

But Z is hard to measure and harder to enforce, so I think we will carry on ignoring it - until we cannot do so any longer.

I don't think punishing people for failed projects is wise. Trial and error is an essential part of innovation: if people fear punishment for mistakes, they won't experiment. And I don't think lenders should be punished for providing capital to projects that fail, either: that is a sure-fire way of ensuring that they only ever invest in safe assets such as property, to the detriment of economic growth (there is significant evidence that property investment crowds out productive lending). If you want higher GDP, you have to encourage both the owners of capital and financial intermediaries to take risks with that money. And that means accepting losses. We have created a culture where the owners of capital expect their money to be safe - hence the preference for debt over equity, and the expectation of sovereign bailout. It's fundamentally dysfunctional.

DeleteGreat for job ,

ReplyDeletejobs

I don't understand why governments have to borrow from bond markets and banks their own currency and pay interest,when through legislation like the NEED Act they can just use their own currency, as long as they don't spend so much as to cause high inflation. I know this is different in the Eurozone, what would be the equivilent legislation there?

ReplyDelete