Laffer and the Loch Ness Monster

Comments on my post "Laffer and the Yeti" forced me to look again at the way in which the Laffer curve is used to argue both for and against raising taxes for the rich. It seems it is widely - and perhaps deliberately - misused.

The Laffer curve illustrates the relationship between elasticity of taxable income and tax revenues. The peak of the Laffer curve is the rate of tax at which tax revenue from all sectors is maximised, because the cost of avoiding tax outweighs the cost of paying it. But it is an AGGREGATE measure. It says absolutely nothing about the distribution of tax rates or tax income elasticities across the population. Yet it is widely used to talk about tax rates for the rich, as if the tax rate of the rich is the same as the tax rate for the entire population. It is not. The average tax rate is much lower. Therefore it is possible for the Laffer curve to be well below its peak even when there are high tax rates for the very rich.

Laffer curves can, of course, be created for individual sectors. So it is possible to create a Laffer curve specifically for those who fall into the top tax bracket (though this is of course a moving target), and then to solve for the revenue-maximising rate of tax for those people. But this tells us absolutely nothing about tax revenues in aggregate. In fact it is sensible to assume that tax revenues are well below the revenue-maximising peak for everyone EXCEPT those falling into the top tax bracket. In which case, we are looking at a marginal effect. What we don't know is how significant that marginal effect is.

In an economy where there are a relatively large number of wealthy people, we would expect that raising tax rates for the rich would have a significant effect on tax revenues. The Laffer curve shows that there is a point beyond which tax revenues start to fall as average tax rates rise. This is not unreasonable, but we don't know where that point is, and estimates vary wildly. But for a wealthy-dominated economy, tax rates on the wealthy that are far to the right of the Laffer curve peak for that sector could indeed have a bad effect on public finances. It's perhaps not surprising that economies dominated by the wealthy do tend to have low top tax rates.

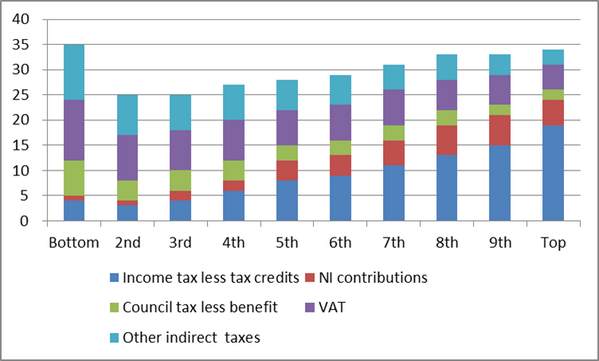

But most economies don't have a relatively large number of wealthy people. They have a relatively small number of wealthy people and a much larger number of people on low to middling incomes. Virtually all of these people pay tax to a greater or lesser extent: indeed in the UK, tax rates as a proportion of income are highest on the very poorest even after taking benefits (negative taxes) into account, because the burden of indirect taxes falls most heavily on them:*

(chart courtesy of Stuart Astill)

We would expect that tax rates for the very rich could be far above the Laffer peak for that sector without seriously adverse effects on the public finances. Yes, tax revenues from this group might diminish, but there could - as Simon says - be very good social reasons for allowing this to happen. We would create a slight inefficiency in tax collection, but then we have tax inefficiencies in all other sectors anyway for social reasons, so why not in this sector too? Why should revenue-maximising be the primary aim for the very rich but not for anyone else? Whatever happened to taxation as an influence on behaviour?

Indeed, high taxation of the rich has been proposed by several economists, not only to improve public finances but to reduce inequality - and to improve the behaviour of corporate executives. If they cannot keep excessive rewards, they are much less likely either to be offered them as wages (bonuses) or to extort them in the form of economic rents.

But this brings me to the second, and arguably more serious problem. It is often argued that high taxes for the rich cause GDP to fall, which hurts the poor - and conversely, that lowering taxes on the rich improves the incomes of the poor. This is "trickle-down economics", or what I dubbed the Loch Ness Monster argument.

The Loch Ness Monster argument, in a slightly different form, states that income inequality is essential for growth, because only the rich generate enough savings for there to be productive investment. If the saving of the rich is impeded by high taxation, private sector investment is also impeded, which over the long-run will reduce GDP and therefore damage the poor as well as the rich. Raising taxes on the rich to restore public finances and improve the lives of the poor is therefore counterproductive over the long-run. Is this argument correct?

There are some pretty heroic assumptions here. The first is that the rich save more than the poor. Individually - and simplistically - they undoubtedly do: the poor are forced to spend most of their income on simply surviving, so save little, whereas the rich can meet all their needs from a relatively small proportion of their income, and (it can be argued) are forced to save the rest.

But what exactly do we mean by "rich" and "poor"? If we were in a Dickensian nightmare world where there were only the very rich (who save most of their income) and the very poor (who save nothing), it would be true. But we are not. "Poor" is relative. These days, most people save to some extent, even if they don't know they do - how many people realise their pension contributions, and their mortgage payments, are actually saving? The very poorest don't, of course, but they are a relatively small proportion of the population - indeed, vanishingly small in countries that have no state pension system. The rest are savers. A vast number of poor-ish saving a little can add up to as much or more than a small number of rich saving a lot. So IN AGGREGATE, in most countries, it is by no means certain that the rich save more than the poor. They could save much less. Indeed, this paper by Schmidt-Hebble and Servern found no relationship between income inequality and aggregate saving.

If this is the case, there would be at least as strong an argument for reducing taxation at low to middle incomes as there is for reducing taxes on the rich. If what we need is more aggregate saving, it doesn't matter who saves, does it? And we do know that those on low incomes are more likely to dis-save when times are hard. Reducing their tax burden should help them to maintain or increase their saving rate.

The second heroic assumption concerns the use that is made of savings. If the poor save primarily by stuffing mattresses or buying gold, then we would indeed rely mainly on the savings of the rich for investment. And in some countries (here's looking at you, India) this is indeed the case. But in developed countries where people place their savings with financial intermediaries, we assume that all savings are productively invested. In which case it doesn't matter whether the savings come from the poor or the rich, does it? Of course, if savings are NOT productively invested we have a bigger problem. And that brings me to the third heroic assumption.

There is an implicit assumption here that paying taxes is unproductive, and the money would have been better used for private sector investment. I won't get into philosophical and political debates about the role of the State, but it is fundamentally illogical to assume a) that all private sector investment is necessarily productive and b) that all public sector investment is necessarily unproductive. How is it more productive for someone to invest their money in government bonds than to pay taxes? It's the same money used for the same purpose! If money paid out in taxation is unproductive, then so is money lent to the government in the form of safe asset purchases. The private sector invests a considerable amount of its untaxed income in government bonds. If all government expenditure is unproductive, then this is unproductive investment.

The only "productive" form of private sector investment is investment in enterprise. It is fair to argue that as this form of investment involves taking risk, the rich are far more likely to invest directly than the poor. But most of the poor place their money with financial intermediaries, who are responsible for providing risk capital to enterprise. So it seems the risk aversion of the poor is another red herring. We are not reliant on the rich for risk capital. We are reliant on financial intermediaries who invest the savings of those on low to middle incomes.

Whether taxation (or investment in government bonds, which is the same thing really) is an unproductive use of funds depends on how the State uses the money. It is often stated that the State is unable to assess risk properly or make rational investment decisions, and that therefore any investments the State makes are likely to be inefficient relative to private sector investments. Frankly I think this is questionable: after all, the State uses the same management consultancies to advise it on investment projects as the private sector does, engages the same contractors as the private sector uses and recruits people from the private sector. Admittedly, bureaucracy can have a deadening effect, but the same is true of large organisations in the private sector. Bureaucratic inefficiency is certainly not a public sector specialism.

But even "normal" use of state funds is not necessarily unproductive. Industry wants educated workers, it wants a well-developed modern infrastructure, it wants workers mended when they fall ill.....there may well be more efficient ways of providing them than the current arrangements, but that does not mean that the State is necessarily a worse provider than the private sector would be. We have to be very careful not to argue from our priors!

The arguments supporting the idea that high taxes on the rich damage the poor are perhaps weaker than their proponents like to admit. However, we know that falling GDP does damage the poor. If higher taxes on the rich DO cause GDP to fall, then there really is a monster in Loch Ness, even if we don't know what it looks like.

Tax increases are undoubtedly contractionary. Romer & Romer show that higher taxation causes GDP to fall. But their paper considers an increase in AGGREGATE taxation from all sources, not a specific increase in taxes on one sector only. I suspect that the GDP fall they identify is caused by opportunity costs (high taxation prevents deployment of funds to more productive investments) and general disincentives to produce. But their work does not show that higher taxation of the rich causes GDP to fall. And Piketty and Saez's paper shows that there has been little if any upside benefit to GDP from cutting taxes for the rich. I suppose there could be some weird kind of asymmetry, whereby raising taxes on the rich damages the poor but cutting taxes for the rich doesn't benefit anyone except the rich, but really this is stretching credibility quite a bit.

If anyone has conclusive evidence that there is a definite causal link from raising taxes on the rich to falling GDP, I would be very pleased to see it. Until then, I remain of the opinion that the Loch Ness Monster is a myth, and so is "trickle-down economics".

Related reading:

The Peak of the Laffer Curve is Not the Place to Be - Bob Krumm

Shifting justifications for the 50p tax rate - Institute for Economic Affairs

Oh no, not again - Coppola Comment

Tax, inequality and the problem of the 50p rate - Pieria

* Indirect taxes in the UK include VAT, and "sin" taxes on tobacco and alcohol. The very poorest spend more of their income on general consumption than anyone else, so are most affected by VAT. And they also proportionately spend more on tobacco and alcohol.

The Laffer curve illustrates the relationship between elasticity of taxable income and tax revenues. The peak of the Laffer curve is the rate of tax at which tax revenue from all sectors is maximised, because the cost of avoiding tax outweighs the cost of paying it. But it is an AGGREGATE measure. It says absolutely nothing about the distribution of tax rates or tax income elasticities across the population. Yet it is widely used to talk about tax rates for the rich, as if the tax rate of the rich is the same as the tax rate for the entire population. It is not. The average tax rate is much lower. Therefore it is possible for the Laffer curve to be well below its peak even when there are high tax rates for the very rich.

Laffer curves can, of course, be created for individual sectors. So it is possible to create a Laffer curve specifically for those who fall into the top tax bracket (though this is of course a moving target), and then to solve for the revenue-maximising rate of tax for those people. But this tells us absolutely nothing about tax revenues in aggregate. In fact it is sensible to assume that tax revenues are well below the revenue-maximising peak for everyone EXCEPT those falling into the top tax bracket. In which case, we are looking at a marginal effect. What we don't know is how significant that marginal effect is.

In an economy where there are a relatively large number of wealthy people, we would expect that raising tax rates for the rich would have a significant effect on tax revenues. The Laffer curve shows that there is a point beyond which tax revenues start to fall as average tax rates rise. This is not unreasonable, but we don't know where that point is, and estimates vary wildly. But for a wealthy-dominated economy, tax rates on the wealthy that are far to the right of the Laffer curve peak for that sector could indeed have a bad effect on public finances. It's perhaps not surprising that economies dominated by the wealthy do tend to have low top tax rates.

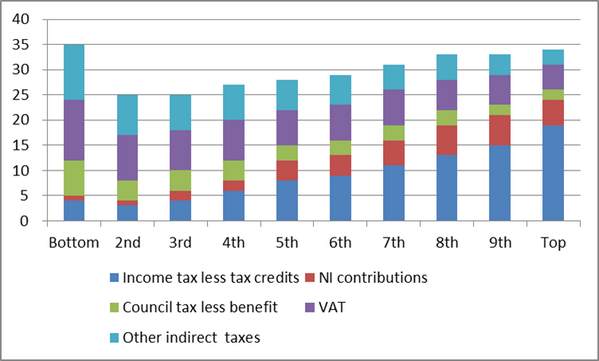

But most economies don't have a relatively large number of wealthy people. They have a relatively small number of wealthy people and a much larger number of people on low to middling incomes. Virtually all of these people pay tax to a greater or lesser extent: indeed in the UK, tax rates as a proportion of income are highest on the very poorest even after taking benefits (negative taxes) into account, because the burden of indirect taxes falls most heavily on them:*

(chart courtesy of Stuart Astill)

We would expect that tax rates for the very rich could be far above the Laffer peak for that sector without seriously adverse effects on the public finances. Yes, tax revenues from this group might diminish, but there could - as Simon says - be very good social reasons for allowing this to happen. We would create a slight inefficiency in tax collection, but then we have tax inefficiencies in all other sectors anyway for social reasons, so why not in this sector too? Why should revenue-maximising be the primary aim for the very rich but not for anyone else? Whatever happened to taxation as an influence on behaviour?

Indeed, high taxation of the rich has been proposed by several economists, not only to improve public finances but to reduce inequality - and to improve the behaviour of corporate executives. If they cannot keep excessive rewards, they are much less likely either to be offered them as wages (bonuses) or to extort them in the form of economic rents.

But this brings me to the second, and arguably more serious problem. It is often argued that high taxes for the rich cause GDP to fall, which hurts the poor - and conversely, that lowering taxes on the rich improves the incomes of the poor. This is "trickle-down economics", or what I dubbed the Loch Ness Monster argument.

The Loch Ness Monster argument, in a slightly different form, states that income inequality is essential for growth, because only the rich generate enough savings for there to be productive investment. If the saving of the rich is impeded by high taxation, private sector investment is also impeded, which over the long-run will reduce GDP and therefore damage the poor as well as the rich. Raising taxes on the rich to restore public finances and improve the lives of the poor is therefore counterproductive over the long-run. Is this argument correct?

There are some pretty heroic assumptions here. The first is that the rich save more than the poor. Individually - and simplistically - they undoubtedly do: the poor are forced to spend most of their income on simply surviving, so save little, whereas the rich can meet all their needs from a relatively small proportion of their income, and (it can be argued) are forced to save the rest.

But what exactly do we mean by "rich" and "poor"? If we were in a Dickensian nightmare world where there were only the very rich (who save most of their income) and the very poor (who save nothing), it would be true. But we are not. "Poor" is relative. These days, most people save to some extent, even if they don't know they do - how many people realise their pension contributions, and their mortgage payments, are actually saving? The very poorest don't, of course, but they are a relatively small proportion of the population - indeed, vanishingly small in countries that have no state pension system. The rest are savers. A vast number of poor-ish saving a little can add up to as much or more than a small number of rich saving a lot. So IN AGGREGATE, in most countries, it is by no means certain that the rich save more than the poor. They could save much less. Indeed, this paper by Schmidt-Hebble and Servern found no relationship between income inequality and aggregate saving.

If this is the case, there would be at least as strong an argument for reducing taxation at low to middle incomes as there is for reducing taxes on the rich. If what we need is more aggregate saving, it doesn't matter who saves, does it? And we do know that those on low incomes are more likely to dis-save when times are hard. Reducing their tax burden should help them to maintain or increase their saving rate.

The second heroic assumption concerns the use that is made of savings. If the poor save primarily by stuffing mattresses or buying gold, then we would indeed rely mainly on the savings of the rich for investment. And in some countries (here's looking at you, India) this is indeed the case. But in developed countries where people place their savings with financial intermediaries, we assume that all savings are productively invested. In which case it doesn't matter whether the savings come from the poor or the rich, does it? Of course, if savings are NOT productively invested we have a bigger problem. And that brings me to the third heroic assumption.

There is an implicit assumption here that paying taxes is unproductive, and the money would have been better used for private sector investment. I won't get into philosophical and political debates about the role of the State, but it is fundamentally illogical to assume a) that all private sector investment is necessarily productive and b) that all public sector investment is necessarily unproductive. How is it more productive for someone to invest their money in government bonds than to pay taxes? It's the same money used for the same purpose! If money paid out in taxation is unproductive, then so is money lent to the government in the form of safe asset purchases. The private sector invests a considerable amount of its untaxed income in government bonds. If all government expenditure is unproductive, then this is unproductive investment.

The only "productive" form of private sector investment is investment in enterprise. It is fair to argue that as this form of investment involves taking risk, the rich are far more likely to invest directly than the poor. But most of the poor place their money with financial intermediaries, who are responsible for providing risk capital to enterprise. So it seems the risk aversion of the poor is another red herring. We are not reliant on the rich for risk capital. We are reliant on financial intermediaries who invest the savings of those on low to middle incomes.

Whether taxation (or investment in government bonds, which is the same thing really) is an unproductive use of funds depends on how the State uses the money. It is often stated that the State is unable to assess risk properly or make rational investment decisions, and that therefore any investments the State makes are likely to be inefficient relative to private sector investments. Frankly I think this is questionable: after all, the State uses the same management consultancies to advise it on investment projects as the private sector does, engages the same contractors as the private sector uses and recruits people from the private sector. Admittedly, bureaucracy can have a deadening effect, but the same is true of large organisations in the private sector. Bureaucratic inefficiency is certainly not a public sector specialism.

But even "normal" use of state funds is not necessarily unproductive. Industry wants educated workers, it wants a well-developed modern infrastructure, it wants workers mended when they fall ill.....there may well be more efficient ways of providing them than the current arrangements, but that does not mean that the State is necessarily a worse provider than the private sector would be. We have to be very careful not to argue from our priors!

The arguments supporting the idea that high taxes on the rich damage the poor are perhaps weaker than their proponents like to admit. However, we know that falling GDP does damage the poor. If higher taxes on the rich DO cause GDP to fall, then there really is a monster in Loch Ness, even if we don't know what it looks like.

Tax increases are undoubtedly contractionary. Romer & Romer show that higher taxation causes GDP to fall. But their paper considers an increase in AGGREGATE taxation from all sources, not a specific increase in taxes on one sector only. I suspect that the GDP fall they identify is caused by opportunity costs (high taxation prevents deployment of funds to more productive investments) and general disincentives to produce. But their work does not show that higher taxation of the rich causes GDP to fall. And Piketty and Saez's paper shows that there has been little if any upside benefit to GDP from cutting taxes for the rich. I suppose there could be some weird kind of asymmetry, whereby raising taxes on the rich damages the poor but cutting taxes for the rich doesn't benefit anyone except the rich, but really this is stretching credibility quite a bit.

If anyone has conclusive evidence that there is a definite causal link from raising taxes on the rich to falling GDP, I would be very pleased to see it. Until then, I remain of the opinion that the Loch Ness Monster is a myth, and so is "trickle-down economics".

Related reading:

The Peak of the Laffer Curve is Not the Place to Be - Bob Krumm

Shifting justifications for the 50p tax rate - Institute for Economic Affairs

Oh no, not again - Coppola Comment

Tax, inequality and the problem of the 50p rate - Pieria

* Indirect taxes in the UK include VAT, and "sin" taxes on tobacco and alcohol. The very poorest spend more of their income on general consumption than anyone else, so are most affected by VAT. And they also proportionately spend more on tobacco and alcohol.

Frances

ReplyDeleteSigh. Just reading this post is tiring.

I have some (better imo) questions.

What should be the purpose of tax collection? Should the goal be to maximize tax revenues? On what should taxes be spent? Define the moral justification for taxation as an influence on behavior?

"If this is the case, there would be at least as strong an argument for reducing taxation at low to middle incomes as there is for reducing taxes on the rich."

Fwiw, I do not make the argument that taxes should only be lowered for the rich.

"If the poor save primarily by stuffing mattresses or buying gold, then we would indeed rely mainly on the savings of the rich for investment."

Buying gold as a form of savings is not unhealthy for productive investment. If all capital is forced into production, then there is bound to be a lot of malinvestment. With another avenue of savings available, malinvestment ( unproductive investment) is curbed, as only productive investment will offer yields high enough to coax savings from gold (assuming reliable and non-manipulated market metrics).

"I won't get into philosophical and political debates about the role of the State, but it is fundamentally illogical to assume a) that all private sector investment is necessarily productive and b) that all public sector investment is necessarily unproductive."

This is correct. However. a) the current system forces unproductive investment to try and search for yield to compensate for inflation. b) Would you argue that all public sector investment is optimally productive?

I would say a small percentage of it may be, a larger percentage not too wasteful, and the rest very wasteful. I would say the arguments for why this is so have been made exhaustively, and that there is no reason to repeat this argument.

"The private sector invests a considerable amount of its untaxed income in government bonds. If all government expenditure is unproductive, then this is unproductive investment."

So shall we simply ignore the elephant in the room which is regulatory capture of private sector funds by law?

It is possible that the private sector may choose to invest some funds in government bonds, if they had free choice. However. I would say the volume of such would be much smaller if there were not regulatory force involved.

"Frankly I think this is questionable: after all, the State uses the same management consultancies to advise it on investment projects as the private sector does, engages the same contractors as the private sector uses and recruits people from the private sector."

Sure. But the goals of private and public investment are dissimilar. In simple terms private investment is about profit whereas public investment is about buying votes and creating popular public sentiment. And let's not even go to cronyism and government tender systems which are completely ruled by political connections, and not at all about efficient use of funds, but rather kickbacks and helping politicians friends and family get rich at taxpayer expense.

"Bureaucratic inefficiency is certainly not a public sector specialism."

Sure, but in a free market, private sector companies are punished for this, whereas public sector bureaucratic inefficiency is rewarded by more allocation of public funds.

"there may well be more efficient ways of providing them than the current arrangements, but that does not mean that the State is necessarily a worse provider than the private sector would be."

Now does it mean that the State is necessarily a better provider than the private sector would be. And given the comments above on incentives and inefficiencies of governments in general, it is certainly arguable that the private sector would ( and do) do a better job.

Motley Fool

"We are reliant on financial intermediaries who invest the savings of those on low to middle incomes." Invest the savings ? A loanable funds model ? Sounds a bit Austrian... ;)

ReplyDeleteI deliberately did not say "banks". Most of the savings of the less-well-off are actually in pension funds - which do operate a loanable funds model.

DeleteAre indirect taxes regressive? The TV licenses and certain sin taxes might be, but not overall based on household expenditure:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/household-income/how-indirect-taxes-can-be-regressive-and-progressive/2001-02---2008-09/art-regressive-and-progressive-taxes.pdf

They appear regressive based on household income because many households with low incomes spend more than they earn by using savings or by borrowing e.g. the 1.6 million early retirees in the UK, students, the temporarily out of work. Many of the lowest income households have had or will have higher incomes at different stages of their lives.

I am not disagreeing in general with anything you have said but just pointing out this quirk.

It is probably also worth mentioning that the published statistics on household incomes and indirect taxes count employer NIC as an indirect tax on consumers rather than a direct tax on employment.

Another heroic assumption in the Loch Ness Monster argument, Frances, is that corporate UK _wants_ external funds (ie from household saving) in order to finance investment at all.

ReplyDeleteThe evidence from national accounts is that aggregate corporate fixed capital formation is internally funded. Corporate UK has been a structural net lender to the rest of the economy since 2001 or so. So whether it's rich or poor households that are the greater savers, or how saving would be impacted by a change in taxation, is in fact irrelevant.

Anders, that's a very good point! Thanks.

Delete"A vast number of poor-ish saving a little can add up to as much or more than a small number of rich saving a lot. So IN AGGREGATE, in most countries, it is by no means certain that the rich save more than the poor. They could save much less. Indeed, this paper by Schmidt-Hebble and Servern found no relationship between income inequality and aggregate saving."

ReplyDeleteI love it when people question assumptions and consult the empirical evidence. Excellent post.

Actually I picked up that paper from a link you posted on WCI. Many thanks, and I apologise for not crediting you in the post.

DeleteBrick Says.

ReplyDeleteI tend to agree except for thinking that one particular point needs exploring further. Namely.

It is often stated that the State is unable to assess risk properly or make rational investment decisions, and that therefore any investments the State makes are likely to be inefficient relative to private sector investments.Frankly I think this is questionable: after all, the State uses the same management consultancies to advise it on investment projects as the private sector does, engages the same contractors as the private sector uses and recruits people from the private sector.

For me the question is not whether the government is better or worse at investment than the private sector, since both seem to make monumentally bad investments decisions on occasions, probably precisely because they do use management consultancies, but whether investment is long or short term (as far as the next election or CEO) and whether decisions have a political element. The money wasted on failed government IT and defense projects could have paid for a lot of free college education, or could have been used to reduce taxes on the poor.Longer term financing (bypassing bond and treasury markets if that is the fear and using banks) could be used for social housing especially considering the queues for housing and the guaranteed income streams, but it does not happen for political reasons. I am not arguing that government should cut spending, in fact just the opposite. I think there needs to be additional policies for the government to structurally change thinking on many things for the long term based on how we want society to work now, otherwise those changes may be more difficult to achieve in the future as society fragments and decays.

Fantastic column, goes through nearly every leftist idiocy possible. It's greatest failing is ignoring incentives. I only have time to rage over a few points, so...

ReplyDelete"Why should revenue-maximising be the primary aim for the very rich but not for anyone else?" Revenue maximizing should never be the aim. The tax system should raise what is needed.

"Whatever happened to taxation as an influence on behaviour?" Disgusting. Behavior is either criminal or legal and who the fuck are you to discourage legal behaviour? Prodnose.

"Indeed, high taxation of the rich has been proposed by several economists, not only to improve public finances but to reduce inequality". And there is still no real argument that inequality is bad. To paraphrase the immortal Thatcher you people would prefer the poor were poorer if it also made the rich less rich.

"...to improve the behaviour of corporate executives. If they cannot keep excessive rewards .." Who gave you the right to tell shareholders that what they propose to pay executives is excessive? First you make me pay excessive minimum wages to pig ignorant losers then you won't let me pay high wages to the best of the best.

" ... income inequality is essential for growth, because only the rich generate enough savings for there to be productive investment." That is not the argument at all. It is essential for growth because many people will only work very, very hard and take great risks if they have a chance to get rich. INCENTIVES MATTER.

I'm not at all sure that your obnoxious rant is really worth wasting time replying to. But I will none the less make a few points.

Delete1. As the whole point of the Laffer curve is finding the revenue-maximising tax rate, your comment that "revenue maximizing should never be the aim" is redundant.

2. You have never heard of Pigouvian taxation, then? And you have the nerve to talk to me about economics?

3. "And there is still no real argument that inequality is bad". So you want to see the rich remain rich and the poor remain poor, then? Everyone in their place? How positively charming. Personally I have no desire to see the poor remain poor, let alone become poorer, and I only wish to see the rich less rich if it means the poor can be less poor.

4. To add to your economic ignorance, you don't seem to know what a principal/agent problem is. What on earth makes you think that shareholders pay executives their real worth?

5. The standard argument in favour of inequality is that only the rich generate enough savings for productive investment. Do keep up.

7. Incentives matter. Yes, indeed they do. I never said they did not. But financial rewards are not the only incentive. Go and read some Maslow.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete