The Great Scandinavian Divergence

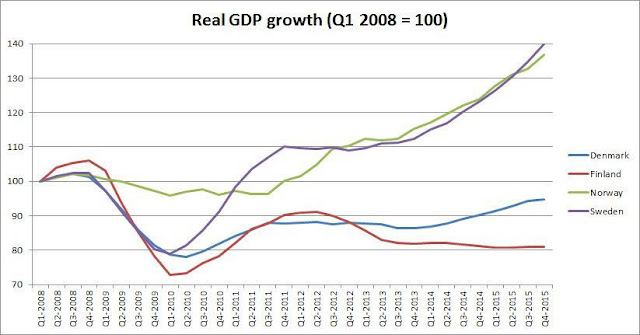

From @MineforNothing on Twitter comes this chart:

Now, we know Finland is in a bit of a mess. A series of nasty supply-side shocks has devastated the economy. When Nokia collapsed in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis, ripping a huge hole in the country's GDP, the government responded with substantial fiscal support. This wrecked its formerly virtuous fiscal position: it switched from a 6% budget surplus to a 4% deficit in one year, and although its deficit has improved slightly since, it is still outside Maastricht limits. Because of this, the current government - under pressure from the insane Eurocrats - is implementing fiscal austerity to bring the budget deficit back below 3% of GDP. For an economy which has suffered a serious reduction in its productive capacity, this is disastrous. The austerity measures will neither reduce the deficit nor restore the economy. On the contrary, they will cause the economy to shrink and consequently - through simple arithmetic - increase the deficit as a proportion of GDP. Finland has been in recession for just about all of the last four years: what it needs is expansionary fiscal policy, not bloodletting. Austerity is an utterly self-defeating policy for an economy which has a damaged supply side due to exogenous shocks.

The one thing that is keeping the Finnish economy from imploding is the ECB's expansionary monetary policy. Negative rates and QE may be a weak stimulus, but they are better than nothing. Finland has been masquerading as a prosperous core country, but the truth is that it is much more like the weak Southern European states:

(US GDP is included for comparison)

Without ECB support, Finland would be in deep trouble.

But what on earth has gone wrong with Denmark? Like Finland and Sweden - and interestingly, NOT like Norway (more on that shortly) - Denmark suffered a deep recession after the financial crisis, hitting bottom in the second quarter of 2010. But unlike Sweden, it did not recover. The pattern of its GDP growth is much more like Finland's. Yet it did not have the supply-side shocks that Finland suffered. Why has it stagnated for most of the last seven years?

Every man and his dog has a theory about this. Most of them focus on Denmark's generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. High taxation stifles enterprise, while the welfare state discourages productive work, apparently. So what Denmark should do is cut taxes and shrink its welfare state. That will make it much more prosperous - though probably no happier.

But hang on. Sweden also has a generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. So does Norway. Indeed, so does Finland. All the Nordic states do. And all of them have made serious attempts in recent years to improve the efficiency of their welfare systems and reduce their cost. Denmark, in fact, ranks higher up the OECD's list of countries by reform effort than any other Scandinavian country. Yet their economic performance differs enormously. Finland and Denmark are performing poorly. Norway and Sweden are performing well - and Norway did not suffer the deep recession of the post-crisis years, either. It is hard to see that Scandinavian welfare and taxation causes this. No, there is some exogenous reason.

The reason is not difficult to find. Finland, the worst-performing of these countries, is a member of the Euro. Not only does this prevent it from managing its own monetary policy, including devaluing to protect its economy from exogenous shocks, but it also chains its fiscal policy to the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact. Finland is in the Excessive Deficit Procedure, and as a Euro member, that means it must comply with the actions required under that procedure or face sanctions - even if those actions are directly harmful to its economy.

None of the others is a Euro member. But Denmark is a member of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) which is a precursor to Euro member. It is obliged to maintain the value of its currency within agreed bands around the Euro. Its monetary policy is therefore determined to a large extent not by local conditions, but by the decisions of the ECB - whether or not they are appropriate for the Danish economy. Denmark has also agreed to be bound by the stricter form of the Stability and Growth Pact known as the Fiscal Compact, which means it is subject to the same fiscal rules and penalties as if it were a member of the Eurozone.

In contrast, Sweden is not a member of ERM II. It is supposed to join the Euro at some point, but - mysteriously - persistently fails to meet convergence criteria. The Swedish krona floats against world currencies including the Euro, giving Sweden much greater control of its monetary policy than Denmark or Finland. On the fiscal side, although Sweden ratified the Fiscal Compact, it refused to allow itself to be bound by its provisions while it remains outside the Euro. So although it is supposed to keep within Maastricht fiscal limits, it does not face penalties for failing to do so.

Norway, of course, is not a member of the EU. Since Norway is an oil exporter, the Norwegian krone is a petrocurrency. Norway has used its sovereign wealth fund effectively to mop up the income from oil production and prevent its currency appreciating excessively. Recent oil price falls nevertheless have hit it hard: January's GDP growth was negative, and it is currently drawing on its sovereign wealth fund to maintain fiscal programmes. It remains to be seen whether Norway's previous responsible management will be sufficient to prevent it slipping into outright recession. But Norway's current difficulties are principally due to global conditions, not because of ties to a depressed and austerity-obsessed Eurozone.

The ability to manage monetary and fiscal policy is precious. Eurozone central banks, locked into a one-size-fits-all monetary policy, have little ability to protect their economies from local shocks; with the centralisation of bank supervision, they have even largely lost control of macroprudential policy. Eurozone fiscal authorities, too, have little autonomy once the country is in the Excessive Deficit procedure; for those outside it, avoiding Brussels supervision can become an overriding concern. For Eurozone countries, the real monetary target is not inflation but deficit/GDP. The ECB is fighting a losing battle trying to raise inflation against the determination of the Brussels bureaucracy to force 19 fiscal authorities to depress demand in the name of balancing the books.

So Finland's economic disaster is at least partly a consequence of its Euro membership. And Denmark suffers from loss of monetary autonomy due to its membership of ERM II, and loss of fiscal autonomy because it chooses to be bound by the Fiscal Compact. Conversely, Sweden has control of both monetary and fiscal policy, while Norway not only has control of monetary and fiscal policy but is further buffered by its large sovereign wealth fund.

The final evidence is provided by this chart:

There seems little doubt. Welfare states, taxation and structural reforms, pfft. The Great Scandinavian Divergence is principally caused by the Euro.

Related reading:

A Finnish cautionary tale

An unjustified rating

Reforms, bloody reforms

Charts 2 and 3 from Arne Petimezas (@APetimezas on Twitter)

Now, we know Finland is in a bit of a mess. A series of nasty supply-side shocks has devastated the economy. When Nokia collapsed in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis, ripping a huge hole in the country's GDP, the government responded with substantial fiscal support. This wrecked its formerly virtuous fiscal position: it switched from a 6% budget surplus to a 4% deficit in one year, and although its deficit has improved slightly since, it is still outside Maastricht limits. Because of this, the current government - under pressure from the insane Eurocrats - is implementing fiscal austerity to bring the budget deficit back below 3% of GDP. For an economy which has suffered a serious reduction in its productive capacity, this is disastrous. The austerity measures will neither reduce the deficit nor restore the economy. On the contrary, they will cause the economy to shrink and consequently - through simple arithmetic - increase the deficit as a proportion of GDP. Finland has been in recession for just about all of the last four years: what it needs is expansionary fiscal policy, not bloodletting. Austerity is an utterly self-defeating policy for an economy which has a damaged supply side due to exogenous shocks.

The one thing that is keeping the Finnish economy from imploding is the ECB's expansionary monetary policy. Negative rates and QE may be a weak stimulus, but they are better than nothing. Finland has been masquerading as a prosperous core country, but the truth is that it is much more like the weak Southern European states:

(US GDP is included for comparison)

Without ECB support, Finland would be in deep trouble.

But what on earth has gone wrong with Denmark? Like Finland and Sweden - and interestingly, NOT like Norway (more on that shortly) - Denmark suffered a deep recession after the financial crisis, hitting bottom in the second quarter of 2010. But unlike Sweden, it did not recover. The pattern of its GDP growth is much more like Finland's. Yet it did not have the supply-side shocks that Finland suffered. Why has it stagnated for most of the last seven years?

Every man and his dog has a theory about this. Most of them focus on Denmark's generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. High taxation stifles enterprise, while the welfare state discourages productive work, apparently. So what Denmark should do is cut taxes and shrink its welfare state. That will make it much more prosperous - though probably no happier.

But hang on. Sweden also has a generous welfare state and relatively high taxation. So does Norway. Indeed, so does Finland. All the Nordic states do. And all of them have made serious attempts in recent years to improve the efficiency of their welfare systems and reduce their cost. Denmark, in fact, ranks higher up the OECD's list of countries by reform effort than any other Scandinavian country. Yet their economic performance differs enormously. Finland and Denmark are performing poorly. Norway and Sweden are performing well - and Norway did not suffer the deep recession of the post-crisis years, either. It is hard to see that Scandinavian welfare and taxation causes this. No, there is some exogenous reason.

The reason is not difficult to find. Finland, the worst-performing of these countries, is a member of the Euro. Not only does this prevent it from managing its own monetary policy, including devaluing to protect its economy from exogenous shocks, but it also chains its fiscal policy to the provisions of the Stability and Growth Pact. Finland is in the Excessive Deficit Procedure, and as a Euro member, that means it must comply with the actions required under that procedure or face sanctions - even if those actions are directly harmful to its economy.

None of the others is a Euro member. But Denmark is a member of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) which is a precursor to Euro member. It is obliged to maintain the value of its currency within agreed bands around the Euro. Its monetary policy is therefore determined to a large extent not by local conditions, but by the decisions of the ECB - whether or not they are appropriate for the Danish economy. Denmark has also agreed to be bound by the stricter form of the Stability and Growth Pact known as the Fiscal Compact, which means it is subject to the same fiscal rules and penalties as if it were a member of the Eurozone.

In contrast, Sweden is not a member of ERM II. It is supposed to join the Euro at some point, but - mysteriously - persistently fails to meet convergence criteria. The Swedish krona floats against world currencies including the Euro, giving Sweden much greater control of its monetary policy than Denmark or Finland. On the fiscal side, although Sweden ratified the Fiscal Compact, it refused to allow itself to be bound by its provisions while it remains outside the Euro. So although it is supposed to keep within Maastricht fiscal limits, it does not face penalties for failing to do so.

Norway, of course, is not a member of the EU. Since Norway is an oil exporter, the Norwegian krone is a petrocurrency. Norway has used its sovereign wealth fund effectively to mop up the income from oil production and prevent its currency appreciating excessively. Recent oil price falls nevertheless have hit it hard: January's GDP growth was negative, and it is currently drawing on its sovereign wealth fund to maintain fiscal programmes. It remains to be seen whether Norway's previous responsible management will be sufficient to prevent it slipping into outright recession. But Norway's current difficulties are principally due to global conditions, not because of ties to a depressed and austerity-obsessed Eurozone.

The ability to manage monetary and fiscal policy is precious. Eurozone central banks, locked into a one-size-fits-all monetary policy, have little ability to protect their economies from local shocks; with the centralisation of bank supervision, they have even largely lost control of macroprudential policy. Eurozone fiscal authorities, too, have little autonomy once the country is in the Excessive Deficit procedure; for those outside it, avoiding Brussels supervision can become an overriding concern. For Eurozone countries, the real monetary target is not inflation but deficit/GDP. The ECB is fighting a losing battle trying to raise inflation against the determination of the Brussels bureaucracy to force 19 fiscal authorities to depress demand in the name of balancing the books.

So Finland's economic disaster is at least partly a consequence of its Euro membership. And Denmark suffers from loss of monetary autonomy due to its membership of ERM II, and loss of fiscal autonomy because it chooses to be bound by the Fiscal Compact. Conversely, Sweden has control of both monetary and fiscal policy, while Norway not only has control of monetary and fiscal policy but is further buffered by its large sovereign wealth fund.

The final evidence is provided by this chart:

Related reading:

A Finnish cautionary tale

An unjustified rating

Reforms, bloody reforms

Like flies in treacle - eurozone countries cannot escape!

ReplyDeleteEuro- Hotel California

ReplyDeleteI've forwarded this to Juncker, Schauble and Draghi. Not holding breath :-)

ReplyDeleteExcellent post - thank you.

ReplyDeleteAt the moment the policies in Finland are targeted to help export industries by slashing costs. This really hurts domestic demand. Comparisons are being made to Sweden and Germany, but in fact Sweden has managed to grow fast without much improvement in its industrial production after 2008. In Finland too, it is domestic demand that has kept the boat afloat.

ReplyDeletehttps://data.oecd.org/chart/4tJP

Your argument that it is the euro(-peg) that is the main driver of Nordic growth divergence seems overblown and not very convincing. First, exchange rate policy has never been, nor is it ever likely to be, a main driver of growth (and thus growth divergence between countries) over the medium to long run. And looking at the current situation, yes, Finland would probably be slightly better off with looser fiscal policy, but nowhere close to Sweden or Norway anyway. For the latter country, more or less everything can be explained by swings in oil-related investment and the net transfers to or from the petroleum fund. And while I am happy that my native Sweden is doing well, there is no compelling case that monetary policy freedom has much to do with it (=hard to see financial conditions being a driver of divergence when everybody are crawling on the same floor). What could be at play, then? Start checking the markedly different demographic development in Sweden compared to Denmark and notably Finland - GDP/capita growth difference is much smaller. And then there is also the slightly disconcerting possibility that a non-trivial share of Swedish growth is linked to the wild rise in real estate prices, including an unsustainable rise in household indebtedness. Add lack of structural reform in Denmark (real laggard in retail service liberalization) and you get an even more nuanced picture. Do please continue writing about the Nordics and the flaws of the euro, but jumping to conclusions will not enhance the case you are trying to make.

ReplyDeleteI was careful not to suggest that the Euro (or more correctly, Brussels and Frankfurt policy actions aimed at preserving the Euro) was the sole cause of the divergence. I said in the post that Norway's performance was driven by the oil price. And I agree about the demographic differences. I do not, however, think that lack of monetary and fiscal autonomy is insignificant. On the contrary, I think it is the major issue. You clearly disagree. That's fine, but don't accuse me of jumping to conclusions. My position is every bit as carefully considered as yours.

DeleteIt may be too easy to side with the blog host here but I really think Frances hit the spot. A floating E/R provides the greatest policy space to achieve domestic objectives. In addition, the lack of monetary (and hence fiscal) policy autonomy means that each negative shock gets amplified through the economy by pro-cyclical impacts on the interest rates and the fiscal stance. This is why Finland has entered the same downward spiral as the rest of the EZ "periphery".

Deletehttps://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=hVn

DeleteThis FRED graph would get Frances point across better. The real exchange of Sweden and Finland vis-a-vis Germany.

So nothing to do with Finland not having anything else to sell than pulp and paper an phones? And Finns still thinking they can afford the wellbeing state without income? Looking at the euro is like saying the patient is sick because it has fever. Graphs are just second hand indicators of that something is wrong but they do not tell the WHY.

DeleteHeidi, my comments about the damaged supply side in Finland are ALL to do with the fact that it has relied far too heavily on Nokia and the wood pulp industry. Indeed I devoted an entire post to Finland's unusual and - as it proved - disastrous reliance on a single company. Finland needs structural reforms to revitalise its supply side. These are virtually impossible to do when the fiscal side is intent on squeezing money from the economy that should go into much-needed investment, and when there is virtually no monetary offset for the over-tight fiscal stance because the country is locked into an incomplete and unhealthy currency union.

DeleteWhen we compare the supply-side factors alluded to in comments with the evolution of the GDP in the graphs, we observe that the Finnish GDP peaked before the great crisis in 4Q2008, and that the post-slump recovery peaked in 2Q2012. However:

Deletea) The Finnish paper industry collapsed during 2008 and never recovered.

b) Nokia Mobile Phones started its rapid collapse to oblivion in 1Q2011.

c) The collapse of the oil price (Finland builds machinery and equipment for the hydrocarbon extraction sector) collapsed in 1Q2014.

d) The sanctions against Russia took effect in 2Q2014.

In other words, there is a disconnect. If paper and mobile phones were so decisive, they should have capped the temporary recovery earlier and stronger. The Russian factor itself came too late to explain the unstoppable slide from 2012 onwards.

Remain the major external factors suggested in the article: the series of fiscal, budgetary and monetary straight-jackets imposed by the EU.

Thus, Sweden, Denmark and Finland participate in the 2-pack, 6-pack and macroeconomic imbalance procedure; however, only Finland and Denmark are bound by the Euro-plus and European Fiscal compacts; and Norway is not following any of these regulations.

6-pack, MIB and Euro-plus took effect in December 2011; the Fiscal compact in January 2013; the 2-pack in June 2013. Precisely during the critical time-frame when the Finnish GDP plateaued and then slumped.

Hence, on the basis of historical data, the argument by Frances Coppola is solid and convincing.

There should be new elections as soon as possible. The old politics does not work anymore and there are politicians which does not have a glue what life in Finland really is like. So called professional politicians have destroyed the country and all the positivity is DEAD! Stubb, Katainen, Urpilainen and Sipila should be kicked out NOW! Maybe even VLADIMIR PUTIN would be better leader for Finland than the ones there is now.

ReplyDeletemartin, you really should not be jumping to conclusions, will not enhance the case you are trying to make.

ReplyDeletefirst, finlands trade with russia has collapsed more than with almost any of euro countries as you should know.

in even more detailed view you see that unemployment has not skyrocketed, still below 10pc, and the profits of finnish comapnies are setting new records for I believe 4th year in row.

That's a show of stunning structural strenght: record profits for businesses with almost bearable unemployment in this enviroment, low level of bankrupcies comparable to roaring naughties and so on.

about defecits, great part of it is caused beacuse of insane tax cuts for companies and share holders by two last cabinets.

man, it almost is like a sort of a tourette syndorme- there just is people who always pronounce "structural reformes" no matter what they intended to say as they open their mouth, and how unrelated it is to the issue.

Please take a look how the economies of Finland, Sweden and Russia have grown since the turn of the century. Finland lies rather neatly between its two neighbours. Therefore you shouldn't perhaps put all the blame on euro.

ReplyDeleteOne should also stress the chronic inability of recent Finnish governments to implement the intended reforms.

What about the Netherlands?

ReplyDeleteLast time I looked, the Netherlands weren't in Scandinavia.

DeleteNeither is Finland.

DeleteStrictly, true. But Denmark, Finland and Iceland are normally regarded as "Scandinavian" - or more correctly Nordic - countries. Netherlands is not.

DeleteThank you for this post! Excellent read.

ReplyDeletems coppola, please really take a closer look to business profits, ( record profits), bankrupcies, payment delay levels of businesses, or any reasonable given standard of business perfomance in Finland.

ReplyDeletethey all show that businesses are presenting stellar performance in given contracting GDP and macro enviroment, simultaneously to almost bearable unemployment and compeletely bearable pubic deficits.

that's one utter insanity to claim that this kind of combination of business profits, unemployment level, and public a-and private- deficits in given GDP developement shows nothing else but stellar structural strenght and adptability.

it's utter insanity to pronounce "structural reforms", regarding the facts.

with best regards,

the same anonymous.

This is a macroeconomic post. The fact is that Finland's macroeconomic performance is poor compared to other Northern European countries. I do not invent these figures. I do however try to explain them: it is a fact that Finland has suffered from the collapse of Nokia, the decline of the paper and wood pulp industries and latterly the effect of Russian sanctions (in both directions). The performance of the remaining businesses may indeed be stellar, but they cannot compensate for the effects of these shocks. When comparing countries, microeconomics doesn't cut it.

DeleteYes, I believe we have very much the same point of view here, that the case is of several simultaneous macro and demand shocks, of which some has been specialy severe for finlad for different reasons. Lack of independet currency and its devaluation then makes things much worse, and even the mentioned demgraphichs certainly has some effects, altough minor.

DeleteWhat I was trying to point out was that "need-for-structural-reformes" mentionend here is poor case, very poor, if you look at the actual numbers and statistics of the micro level.

in the conditions of contracting gdp there can not be serious structural prolems. if there were would be hearing of bankrupcies and businessess making losses, what they certainly are not doing and again, altough unemployment slowly rises it is still just 9.4% whic I consider very good, under circumstanses.

thank you again,

the same anonymous

at ths point could be good to held a brief news update from finland as the story really is unfolding.

Deletejust yesterday cabinet unconditionally whitdrew its proposed laws for cutting wages and holidays, law given in the purpose of "internal devaluation" and meant to threaten employees unions to agree on wage cuts in the traditional local bargaining system, or that law were to be applied.

that's like the most spectacular and still smoking train wreck in the political history of the nation we just have here as I write, and I must confess I found proceedings really amusing.

main problem was that the proposed laws were found whether unconstituional if effective or ineffective if executed constitutionally, that's some technicalities here.

So it looks like the cabinet is incapable to proceed with legal means in "internal devaluation" and the establishded local bargaining system between employers and employees unions is left to its traditional own devices in wage bargaining.

so no one is like holding his breath right now to see employees unions to agree on wage cuts, so utterly has the present cabinet succeeded to piss of employees side, if you pardon me my french.

this is rather long story, and really should need more detailed view of the local bargaining system, which is rather complicated ad perhaps not perfectly in right place over here.

but the train wreck we just saw, it was huge and sweet indeed.

I really see it as a very good result as now employees unions most likely will keep domestic demand afloat, which is of course their purpose always and also crucial to GDP development right now.

the same anonymous,

..and all of that, ie imminent failure to execute "internal devaluation", is of course one case more for independent floating currency and against euro,

Deletethe same anonymos

TBH this happened mostly because of deep level of incompetence the current hard line austerity represents. It's really astonishing how they succeeded not to, it really should have been a breeze to agree in local bargaining system, but no. The cabinet were so full that neoliberal BS that they first must pss off emploees unions compeletely with that silly dogmatic suplly side rhetoric.

employees unions were fully prepared to agree wage cuts, but they are no more.

this has been really on astonishing display of stupidity on behalf of cabinets, based to political obsessions. You see, someone like Olli Rehn currently holding a seat in the cabinet represent somewhat moderate views with regards to irrational austerity obsessions.

oh boy.

Deletethe trainwreck formerly known as cabinet of finland, it is still moving.

it is currently generating pile that high that it might be just possible that trainwreck formely known as full frontal asuterity cabinet of finland might actually start thinking that quitting euro could be less painfull experience than continuing negotiations with employees unions.

we are living priceless moments here just now.

In Finland businesses have received tax cuts and benefits several times earlier and none of those times have resulted in increase in living wage jobs.

ReplyDeleteIn fact, the result is current situation, where businesses are demanding more and more while cutting salaries and increasing work times.

Finland happens to be the least densely populated country in the eurozone, with a cold climate with high need for energy. It's basically an island.

ReplyDeleteIt's also the furthest away from the center of europe with a language that only five million people talk.

Finland also industrialized later and industrilization relied heavily on state enterprises.

How would it be possible for Finland to do well with same currency and similar policies than countries in the center of Europe? Convergence of politics and economy leads to divergence in areal prosperity?

Maybe Finland (and other periphery countries) is from now on a bit like southern Italy or eastern Germany but without the monetary transfers from prosperous areas.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteSweden along with Denmark is following the current fad for negative interest rates although your article highlights the divergence between the two countries. Any thoughts on why this is the case ? Following your earlier articles is this a devaluation ploy possibly?

ReplyDeleteDifferent reasons, but neither is really a devaluation ploy. The devaluers are the SNB (defensively), the ECB and the BoJ.

DeleteDenmark's negative rate on central bank deposits is intended to defend its currency. Expansionary monetary policy by the ECB puts upwards pressure on the krone due to capital flight, so Denmark has to push down on interest rates in order to hold the ERM II peg. Maintaining depo rates below the ECB's should deter inflows of capital from investors looking for yield.

Sweden's reason is different. Sweden has had persistently low inflation since 2012. The Riksbank's negative rates (on both deposits and funding) are intended to raise inflation to target. Inflation has been slightly above zero since negative rates were introduced, but you wouldn't exactly call the effect scintillating - though January CPI growth did jump to 0.8%.

Excellent post.

ReplyDelete"The Great Scandinavian Divergence is principally caused by the Euro."

ReplyDeleteOf course it is. So let's break up the euro? Now I am a bad guy who wants to fall back to nationalism, who doesn't share the dream of Europe. :) So it is groupthink and denial, and even by those who understand that euro is flawed. And it is not a joke. Millions of people without jobs, youth without hope etc.

"Europe needs to be reformed" Every way you slice it, it cannot be reformed. People didn't sign up for fiscal transfer union and loss of sovereignity that It requires. Daniel Cohn-Bendit ja Guy Verhofstadt in their book http://www.amazon.com/For-Europe-Guy-Verhofstadt/dp/1479261882 postnational Revolution for Europe say it. It is either federal fiscal transfer union or it breaks up. But you see, we are not having this conversation. People in Europe don't know it. We have far right an d some left who want to breal It up, but most europhiles talk is towards reforms. Beats me what they have in mind.

Eurozone fiscal authorities, too, have little autonomy once the country is in the Excessive Deficit procedure; for those outside it, avoiding Brussels supervision can become an overriding concern. For Eurozone countries, the real monetary target is not inflation but deficit/GDP. The ECB is fighting a losing battle trying to raise inflation against the determination of the Brussels bureaucracy to force 19 fiscal authorities to depress demand in the name of balancing the books.

ReplyDeleteThis is classic neofunctionalist spillover theory; once they're committed to monetary policy integration, inevitably, they will miss a budget target, and then they come under EDP, which means effectively that fiscal policy is transferred to the European Commission. It's how the project is meant to work.

I hesitate to sound a critical note, since your excellent articles are generally so informative and well-presented. And I agree with the substance of this one. But it seems to me that the tone of the language you use about the EU reveals your mistaken view about where the responsibility lies for the austerity policy disaster. And if you’re wrong about the responsibility, then you’re likely to be wrong about how to go about sorting it.

ReplyDeleteOn the tone, I plead for you to rethink a bit and find something more balanced and useful to say than “insane eurocrats” (my heart went out to you for the mental abuse of this nature you yourself suffered online), or more pertinent than “the determination of the Brussels bureaucracy to force 19 fiscal authorities to depress demand in the name of balancing the books”.

Why ? Well, because you’re hitting the wrong target.

The eurocrats don’t make the rules. The rules of the Eurozone, starting with the fiscal compact and continuing more or less downhill ever since, are fixed by politicians at the head of national governments. And the fact is that most governments in the Eurozone believe in the doctrine of balanced budgets. And a policy of austerity to achieve it. Many finance ministers themselves think that the state needs to balance its budget in exactly the same way as they believe households do. And the fact is that most people who vote in elections also seem to believe this. Why that is so - in defiance of all reason and fact - is a subject in itself. But it’s true.

So the Eurozone austerity fever simply reflects the democracy which operates in each country.

It doesn’t make sense to blame eurocrats for this. Their job is to implement the rules. You could certainly criticise them for rigidity in doing that or even stupidity in presenting their reports. But saying that the Brussels bureaucracy is ‘forcing’ balanced budgets on the very fiscal authorities who desperately want austerity doesn’t make sense. Eurocrats were never in favour of expanding the eurozone to include economies like Greece’s in the first place.

If anything, the message from the eurocrats has tended to push Germany to increase spending. They’ve ignored it. But when members of the Commission - often former ministers and prime ministers - are nominated by governments of a dominant political ideology, what do you expect ?

It wouldn’t be reasonable to ask eurocrats to criticise the rules, since democracy demands public servants follow political decisions rather than undermine them. But you could ask them to propose changes, even if they would be rejected by Germany and several other countries. Lack of courage, perhaps, rather than insanity.

What about Greece or Portugal ? Well, they were certainly forced. Mainly, especially for Greece, by an unholy Franco-German alliance by ideological governments desperate to avoid facing their electorate with more bank bail-outs. They managed to drag in stories of lazy foreigners and all the rest, coopt the IMF and Commission as enforcers and impose balancing the books on people that were least able to bear the consequences.

But what does it matter if you blame Brussels and the eurocrats ? Who cares ? After all, it chimes with the current mood of Brussels-bashing. Well, that’s what’s wrong with it. Because the politicians who really should be bashed get let off the hook. It’s easier to blame eurocrats than the more difficult task of taking on the small groups of powerful and self-serving people who find themselves at the head of governments in many parts of Europe.

What is to be done ? Tackle the root of the problem - the ideology of balanced budgets that forces needless hardship on millions for the sake of the powerful few. The ideology that demonises foreigners and those different from ourselves.

You’ve written so well about those issues. Don’t let yourself be distracted !