The dangers of historical taboos

The Group of 30 central bankers and economists has produced a new report, "Fundamentals of central banking: lessons from the crisis". It traces the history of central banking theory and practice, including the economic thought that underlies it. And it draws from it some important lessons about the causes of the 2008 crisis and the reasons for the very long, slow recovery. I've discussed the main themes of the report here (Forbes).

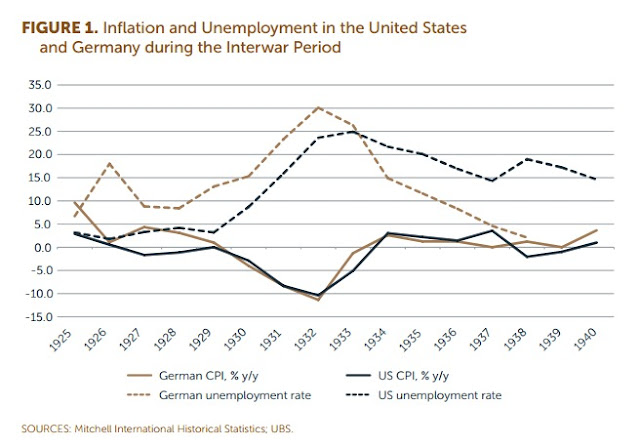

But in this post, I want to focus on a particular piece of economic history. This chart leapt out at me from the report:

Note that this chart starts only two years after the Weimar hyperinflation, hence Germany's elevated inflation rate at the start. This is important, as we shall see.

What struck me is how similar the profiles of the two countries are during the Depression. Both experienced Fisherian debt deflation - annualised CPI fall at peak was 10% for both countries. And both had very high levels of unemployment. German unemployment was actually higher than American, peaking at 30%.

But the recovery was very different. German unemployment fell rapidly during Hitler's tenure, while US unemployment remained elevated until after World War II. Looking at this chart, an alien from Mars who knew nothing of the history of the 20th century might think that the German government did a far better job of restoring its economy than the American government. After all, full employment is always a good thing, isn't it?

Hitler achieved that remarkable fall in unemployment through debt default, autarky and a massive programme of public works. Clearly, this works. So why do we avoid his approach like the plague?

The simple answer is that autarkic governments are usually brutal ones. They don't necessarily start that way, but that is what they become, as people fight against the closed economy and the ever-increasing levels of central control needed to keep it that way. Further, because autarky deprives countries of resources they can't produce themselves, autarkic governments often have expansionary ambitions; instead of trading for goods and services, they seize the means of producing them.

Hitler presided over one of the most murderous governments in history, directly responsible for the deaths of an estimated 13 million people. His attempt to create a European empire ended in defeat and destruction after the most expensive war in history. Looked at from this perspective, that remarkable fall in unemployment doesn't look so good, does it?

The US remains deeply scarred by the memory of unemployment. Google "Great Depression", and you are presented with pictures of soup kitchens, migrating farm workers and queues of out-of-work men, all of them from the United States: it is difficult to find pictures from other countries. We still read the novels of Steinbeck and the speeches of Franklin D. Roosevelt, both icons of this time. Many of the structures and policies put in place at that time to end unemployment remain today: for example, the Federal Reserve's mandate is as much to keep unemployment low as to maintain price stability, and both mainstream and heterodox economists wax lyrical about negative effects of tax and welfare changes on unemployment.

But even though the Great Depression in Germany was similar to that in the US, and German unemployment was actually higher, it does not seem to have left such lasting scars. It is the hyperinflation a decade earlier that is burned into German memory. Images of wheelbarrows full of cash, and walls papered with banknotes, are the iconic images of Germany's interwar disaster. And although this is often forgotten outside Germany, Germans still remember with horror the crippling public debt that blighted their economy and caused the Weimar and Danzig hyperinflations. The German obsession is thus with debt and inflation, rather than unemployment.

This might of course be due to the fact that German unemployment did not remain elevated for as long as unemployment in the US did. But I wonder if there is another reason.

Much of the "public works" was arms production, as Hitler prepared to take over the rest of Europe. You can end unemployment by starting wars. And we can't forget the work ethic of the concentration camps, either. "Arbeit Macht Frei", it says over the gate of Auschwitz - "Work Makes [You] Free". To start with, at least, people were sent to concentration camps to be worked to death, though later "work" was bypassed and the camps became merely killing grounds. You can end unemployment by making large numbers of people slaves, whom you can pretend are not "people" (this is of course also a very painful part of the US's history).

So I wonder if the means by which Hitler ended unemployment in the 1930s has actually left another scar, deeper and far more painful. Could it be that the reason why Germans remember hyperinflation and debt, rather than unemployment, is that the means by which the unemployment of the 1930s was brought to an end is too horrible to contemplate? Does this explain why successive German governments since World War II have resorted to mercantilism (export-led growth founded on repression of domestic demand), rather than public works, to keep unemployment low? And does this also explain the apparent callousness towards other EU countries that have both very high unemployment and very high debt?

I know that Germany wants to put the horror of its past behind it. But mercantilism and autarky are closely related, and the autarkic policies of previous German governments have twice resulted in world wars. Why is it taboo to suggest that mercantilist policies by the current German government might not end too well, and German hegemony in Europe might not turn out to be benign?

Nor do I wish to restrict my discussion of taboo subjects to Germany. We tamely accept and even encourage mercantilist policies in other countries. Yet history tells us that these lead to conflict at home and wars abroad. Why is it taboo to suggest that this time might not be different?

I am very uneasy about taboo subjects in historical analysis. If we are afraid to look at history, we cannot learn from it: and if we cannot learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.

Related reading:

A poignant reminder

Morality in the Greek crisis

Fear the fear

Currency wars and the fall of empires - Pieria

But in this post, I want to focus on a particular piece of economic history. This chart leapt out at me from the report:

Note that this chart starts only two years after the Weimar hyperinflation, hence Germany's elevated inflation rate at the start. This is important, as we shall see.

What struck me is how similar the profiles of the two countries are during the Depression. Both experienced Fisherian debt deflation - annualised CPI fall at peak was 10% for both countries. And both had very high levels of unemployment. German unemployment was actually higher than American, peaking at 30%.

But the recovery was very different. German unemployment fell rapidly during Hitler's tenure, while US unemployment remained elevated until after World War II. Looking at this chart, an alien from Mars who knew nothing of the history of the 20th century might think that the German government did a far better job of restoring its economy than the American government. After all, full employment is always a good thing, isn't it?

Hitler achieved that remarkable fall in unemployment through debt default, autarky and a massive programme of public works. Clearly, this works. So why do we avoid his approach like the plague?

The simple answer is that autarkic governments are usually brutal ones. They don't necessarily start that way, but that is what they become, as people fight against the closed economy and the ever-increasing levels of central control needed to keep it that way. Further, because autarky deprives countries of resources they can't produce themselves, autarkic governments often have expansionary ambitions; instead of trading for goods and services, they seize the means of producing them.

Hitler presided over one of the most murderous governments in history, directly responsible for the deaths of an estimated 13 million people. His attempt to create a European empire ended in defeat and destruction after the most expensive war in history. Looked at from this perspective, that remarkable fall in unemployment doesn't look so good, does it?

The US remains deeply scarred by the memory of unemployment. Google "Great Depression", and you are presented with pictures of soup kitchens, migrating farm workers and queues of out-of-work men, all of them from the United States: it is difficult to find pictures from other countries. We still read the novels of Steinbeck and the speeches of Franklin D. Roosevelt, both icons of this time. Many of the structures and policies put in place at that time to end unemployment remain today: for example, the Federal Reserve's mandate is as much to keep unemployment low as to maintain price stability, and both mainstream and heterodox economists wax lyrical about negative effects of tax and welfare changes on unemployment.

But even though the Great Depression in Germany was similar to that in the US, and German unemployment was actually higher, it does not seem to have left such lasting scars. It is the hyperinflation a decade earlier that is burned into German memory. Images of wheelbarrows full of cash, and walls papered with banknotes, are the iconic images of Germany's interwar disaster. And although this is often forgotten outside Germany, Germans still remember with horror the crippling public debt that blighted their economy and caused the Weimar and Danzig hyperinflations. The German obsession is thus with debt and inflation, rather than unemployment.

This might of course be due to the fact that German unemployment did not remain elevated for as long as unemployment in the US did. But I wonder if there is another reason.

Much of the "public works" was arms production, as Hitler prepared to take over the rest of Europe. You can end unemployment by starting wars. And we can't forget the work ethic of the concentration camps, either. "Arbeit Macht Frei", it says over the gate of Auschwitz - "Work Makes [You] Free". To start with, at least, people were sent to concentration camps to be worked to death, though later "work" was bypassed and the camps became merely killing grounds. You can end unemployment by making large numbers of people slaves, whom you can pretend are not "people" (this is of course also a very painful part of the US's history).

So I wonder if the means by which Hitler ended unemployment in the 1930s has actually left another scar, deeper and far more painful. Could it be that the reason why Germans remember hyperinflation and debt, rather than unemployment, is that the means by which the unemployment of the 1930s was brought to an end is too horrible to contemplate? Does this explain why successive German governments since World War II have resorted to mercantilism (export-led growth founded on repression of domestic demand), rather than public works, to keep unemployment low? And does this also explain the apparent callousness towards other EU countries that have both very high unemployment and very high debt?

I know that Germany wants to put the horror of its past behind it. But mercantilism and autarky are closely related, and the autarkic policies of previous German governments have twice resulted in world wars. Why is it taboo to suggest that mercantilist policies by the current German government might not end too well, and German hegemony in Europe might not turn out to be benign?

Nor do I wish to restrict my discussion of taboo subjects to Germany. We tamely accept and even encourage mercantilist policies in other countries. Yet history tells us that these lead to conflict at home and wars abroad. Why is it taboo to suggest that this time might not be different?

I am very uneasy about taboo subjects in historical analysis. If we are afraid to look at history, we cannot learn from it: and if we cannot learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.

Related reading:

A poignant reminder

Morality in the Greek crisis

Fear the fear

Currency wars and the fall of empires - Pieria

Yes, I agree:

ReplyDelete"We tamely accept and even encourage mercantilist policies in other countries. Yet history tells us that these lead to conflict at home and wars abroad. Why is it taboo to suggest that this time might not be different?"

I am very uneasy about taboo subjects in historical analysis. If we are afraid to look at history, we cannot learn from it: and if we cannot learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.

I like your arguments, but surely modern mercantilism is exercised through the reserve currency system, finance, control of standards, control of commercial law and control of the world bank and the IMF. The victims are the less developed and emerging economies. The resulting wars have been with us for a long time and as the global money system stresses under the weight of theft and corruption the wars are intensifying.

ReplyDeleteA big part of the impact was that the average free german didn't really suffer from war until the near end.

ReplyDeleteAnother big focus probably should be the colonial period ethos, where Germany and Japan were pretty homicidally trying to catch up to advanced countries, specifically in getting colonies and markets for German and Japanese goods. In both countries, finding captive markets were a priority in a world where the other powers has all the best colonies and captive markets. In both countries, frustration of national aims comes directly from how easy it was to interdict trade to and from those countries. For example, think about how despite the success of the Japanese armed forces in the 19th century against China and Russia, they had much less access to Chinese markets and resources than they'd have had they been Western countries. In the present day, with militarism highly constrained as an option for Germany and Japan, preventing an unwanted autarkic situation is a priority, and by being successful in the terms of trade is the key means of doing so.

hmm, to make a couple of more complete thoughts.

Delete1) First statement was about WWII and compared to memories of Weimar. Suggesting that end came so fast and so irrational, people couldn't really think about what happened other than it happened.

2) Japan and China territory, skipped the part where the Western Powers had enough power to negate Japan's gains in what was called the Triple Intervention. Check that out on Wiki--one of the more significant historical actions that people never talk about.

I am a mathematician who taught for a few years and then entered the computer field when computers were just being introduced into American business. I spent 30 years designing and developing large-scale computer systems for large enterprises. I was on a small team that developed one of the first Medicare systems which quickly became the most widely used--at one time it processed every Medicare claim in the country. I then worked to develop a similar system for Medicaid.

ReplyDeleteI never paid much attention to economics until 2004. I have spent the last 11 years designing new government systems, at all levels, and a new economic system for America. This required me to study economics. In my working life, I retired in 1995, I studied many kinds of business systems, most of them were financial in nature, and I always was able to understand the requirements of each and to apply the latest technologies. But economics has nearly beaten me. I had great difficulty in understanding it I would study and study and ask myself "Why can't I get it?" Finally I decided that I was either a dunce or economics does not make sense. Naturally I chose the latter option. Since that time I have been able to design a system that, if implemented, would transform the economic life in the United States. It is completely different from the present system. I say all of this to show that I have tried, really tried, to understand economics and I have failed. I therefore must ask, how can you keep arguing and commenting about economic problems which repeat themselves through a decades long cycle with no let up? Do you honestly think that the way economics is practiced in the US makes sense? When has the system ever worked? It always to be in crisis. I know that a well-designed system should go for very long periods without interruption or drama, but our economic system, which I call tyranno-capitalism is constantly in turmoil. Does everyone in the world think that tyranno-capitalism is the right system for humankind?

As someone who also wrestles with economics, looking for rationality I was interested in your post. As I see it there has been a global imposition of "tyranno-capitalism", emerging from the mercantilism of the UK and other European imperial countries. Where as internally developed countries have developed the rule of law to exclude the worst excesses of this system, internationally the rule of law is weak. The result, under US dominance, has been the evolution of the system, such that we have a modern mercantilism, embedded in institutions and fabric of international trade and communications. Not being specifically US policy, the resulting concentrations of wealth have resulted in a massive corruption, in which nothing is quite what it seems. The values used in trade assume a vast disparity in the value of human life and the environment in different parts of the world, this disparity being nothing but an artifact of a distorted system. Financial risk management is used as a complex means of theft rather than the sharing of risk by informed equals. Financialisation is used as a means to steal assets through arbitrage, with public funds and personal savings funds frequently deployed to inflate asset values and maximise arbitrage opportunities. Through the funding of political parties and lobbying a proportion of the resulting gains are invested in ensuring such opportunities are expanded and that the rule of law will not be a constraint on activities, either at home or internationally. Any government unwilling to expose its assets to financialisation is liable to sanctions or military attack. This allows for a vast and rapid expansion of money created as debt, but ultimately creates a global economy enslaved by oligarchs that control the enforcement of the debts. The feedback loop is the decline in demand as private debt exceeds all possibility of repayment, creating further pressure for more financialisation, and exploitation of people and the environment, together with further military conflict. With no international agreement on sovereign defaults, governments capacity to assume debts on behalf of its people is severely constrained. This in effect places everyone and everywhere in the tyranny of a corrupt and lawless capitalism dominated by individuals who are as disgusted by the outcome as anyone else, apart from having the comfort of knowing that they are not as vulnerable. In parallel, there is a real economy of people with a passion and purpose to use their productive talents for the greater good, for whom the background corruption is part of the business environment in which they have to operate.

DeleteI am a mathematician who taught for a few years and then entered the computer field when computers were just being introduced into American business. I spent 30 years designing and developing large-scale computer systems for large enterprises. I was on a small team that developed one of the first Medicare systems which quickly became the most widely used--at one time it processed every Medicare claim in the country. I then worked to develop a similar system for Medicaid.

ReplyDeleteI never paid much attention to economics until 2004. I have spent the last 11 years designing new government systems, at all levels, and a new economic system for America. This required me to study economics. In my working life, I retired in 1995, I studied many kinds of business systems, most of them were financial in nature, and I always was able to understand the requirements of each and to apply the latest technologies. But economics has nearly beaten me. I had great difficulty in understanding it I would study and study and ask myself "Why can't I get it?" Finally I decided that I was either a dunce or economics does not make sense. Naturally I chose the latter option. Since that time I have been able to design a system that, if implemented, would transform the economic life in the United States. It is completely different from the present system. I say all of this to show that I have tried, really tried, to understand economics and I have failed. I therefore must ask, how can you keep arguing and commenting about economic problems which repeat themselves through a decades long cycle with no let up? Do you honestly think that the way economics is practiced in the US makes sense? When has the system ever worked? It always to be in crisis. I know that a well-designed system should go for very long periods without interruption or drama, but our economic system, which I call tyranno-capitalism is constantly in turmoil. Does everyone in the world think that tyranno-capitalism is the right system for humankind?

Prof. Wren-Lewis, in his blog post

ReplyDeletehttp://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2015/06/what-is-it-about-german-economics.html,

links to a paper which argues that "Germany’s current obsession with inflation...can be traced to a post-war clash of interests between the West German central bank and government concerning the monetary authority’s independence." My comment on Prof. Wren-Lewis's post was more along the lines of Frances Coppola's current post: "...perhaps the reason Germans and Finns (Finland had a Nazi-allied government early in World War II) do not now look upon Keynesian policies favorably is that in 1930's Germany, the economic policy of odious fascists was very similar to 'military Keynesianism' (which was not supported by John Maynard Keynes himself)."

---Gabriel A. Lozada

I find the constant references to Germany's alleged "obsession" with inflation questionable: the average rate of inflation in Germany over the last 20 years and the 70 years since WWII has been very near the 2% target.

Delete"So I wonder if the means by which Hitler ended unemployment in the 1930s has actually left another scar, deeper and far more painful. Could it be that the reason why Germans remember hyperinflation and debt, rather than unemployment, is that the means by which the unemployment of the 1930s was brought to an end is too horrible to contemplate?"

ReplyDeleteUnemployment was not brought to an end by having concentration camps in Germany - that is the complete and utter nonsense. Let us keep concentration camps and slavery on the one hand and public works issues , on the other hand, separate.

What is true, that Germans are very well aware of the fact that the public works programs provided work and led to lower unemployment. That is why Hitler was popular, and that is what is remembered.

The reason "mercantilism" rather than "autarky and public works" are pursued in Germany now, are because the economic debate in Germany has been dominated by think-tanks which are financed by employer organisations. Who argue that Germany has to be competitive by lower wages and increasing exports. Which helps the export orientated German industry, and their profits. And brain-washes Germans that the neo-liberal economics theories are the only ones to be followed.

As the rest of Germany is pretty much economically illiterate, from he finance minister down, these recipes for growth are followed. And because Schaeuble is completely ignorant of any economics, there is an obsession with government debt and deficits. And nothing else.

However, there is of course an obsession against issuing money in Germany, notwithstanding the fact that the economic recovery in the early thirties was financed largely through issuing money. Which did not lead to inflation!

This is conveniently forgotten

"Unemployment was not brought to an end by having concentration camps"

DeleteI did not say it was. But concentration camp inmates were excluded from unemployment statistics. In fact all "undesirables" were excluded both from paid work and from statistics. Hence my observation that redefining certain groups as "not people" can end unemployment.

You don't seem remotely concerned that the public works were dominated by rearmament, nor that autarky was a precursor to external aggression.

Unemployment is virtually non-existent in Germany, before the first concentration camps are opened around 1940.

Deletehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Nazi_concentration_camps

Redefining unemployment statistics is a favourite of any government. The UK started to pay Incapacity benefit to people who qualified, which reduced the unemployment figures in the 1990s.

I do not know why you get the impression I am not concerned about arms production. And (just in case somebody would get the wrong impression) clearly, what happened in Germany between 1933 and 1945 was absolutely abhorrent.

Let us look, however, at the argument that arms production reduced unemployment. It did, but other, more socially useful public works projects would have done the same. Now clearly, if you want to start a war, arms production makes more sense, than building amusement parks.

Germany also knew that in a war it would have difficulties importing supplies, and therefore tried to be as autark as possible.

There was an intention to go to war from the beginning, and that intention came first, and therefore autarky was part of the strategy to ensure that aggression would be successful.

Though prior to WWII the concentration camp population was quite small and declining --- I don't think more than perhaps 100,000, mainly political prisoners. (During the War, the camp system and its populations of course ballooned, but at that point there was of course no longer an unemployment problem.)

DeleteAs regards removing "undesirables" from the workforce and the statistics more generally: again -- apart from one particular exception -- the numbers probably won't bear out your hypothesis that the need to create jobs was somehow linked to or at least benefited much from eliminating "undesirables" via the KZ or general socio-economic & statistical exclusion:

Unemployment peaked in 1932/1933 at around 6 million unemployed, if memory serves. The German Jewish population numbered about 500,000. Let's assume that 60% of these were of working age and actively seeking work (probably a high estimate, but let's be generous). 300,000 is just 5% of 6 million. Even if we add on another 300,000 "politicals" or otherwise "undesirables" eliminated from the workforce, we'd still have only made it to 10% of the total number of peak unemployed. In other words, their elimination from the labour force and labour statistics would not make a great difference.

Higher professional services and jobs requiring university education generally might be an exception: to the extent that a disproportionate number of those persecuted in the 1930s were university-educated -- and Jews in particular rapidly purged from the professions -- that might indeed have created a noticeable job-market opening. That would not have been statistically of much significance with regard to unemployment figures, but it could well have been politically significant: the Nazis were disproportionately supported by young people, and esp. had a large following among young university graduates. So driving Jews and other "undesirables" from the Professions might have made good political sense: creating jobs and thus rewards for a key political support group - young social elites (qua university educated).

I do feel obliged to point out that you haven't actually provided any evidence that the Hyperinflation is somehow more deeply seared into the public German mind (whatever precisely that is) than Depression-era unemployment. I for one am quite doubtful about that hypothesis (but to be fair, don't have contrary evidence either, beyond "knowing" that pretty much no Hitler-related course in German schools will be complete without references to mass unemployment).

Dachau was opened in 1933. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005263

DeleteDachau, Buchenwald etc. were originally forced-labour camps. As I said, they morphed into death camps later on. One of the peculiar things about Auschwitz is that despite its famous motto, it was never a forced-labour camp. It was a purpose-built death camp. But its motto was emblematic of the work ethic of the forced-labour camps.

Autarky was not a means, it was a cause. Hitler intended Germany to be self-contained and self-sufficient. To that end, he aimed to recover the areas ceded to Poland and France in the Versailles Treaty, the loss of which had wrecked much of Germany's industrial capacity. The loss of Silesia is still an issue for right-wing Germans today. We should try to understand how Hitler's expansionary aims were born from the dreadful decisions made by the Allies after WWI.

"The simple answer is that autarkic governments are usually brutal ones."

ReplyDeleteOne of the most brutal regimes has been the US with its constant bombing campaigns against various perceived enemies in the last 50 years.

The USA is not autark but pretty brutal when it comes to pursuing its political interests. So I think we can safely say that autarky and brutality do not necessarily go hand in hand. In fact I would say that in an effort to control the world's oil resources, the USA has been the most brutal of all governments.

The fact that non-autarkic regimes can also be brutal does not invalidate my observation that autarkic regimes tend to be brutal.

DeleteHow about Cuba?

DeleteWas pretty much autark in the 1990s, and was not aggressive towards its neighbours.

A big part of the problem with the discussion around mercantilism is that the anti-mercantile case is largely expounded using examples of dominant economies.

ReplyDeleteIf you are small in world GDP terms (many countries) or if you psychologically believe you are the underdog (Germany & China) then the case against mercantilism is much like the case against austerity. Technically correct but in conflict with "common sense" & politicians find common sense very easy to use for re-election purposes.

for me the important question is that autarky is in the origin of aggressivity. Is not that the first lesson of econmics, that we learn forn Adam Smith, some century ago? Mercantilism was a doctrine based on the absolute power of the monarchy. Is not inimaginable demcracy without free trade? free trade is the first enemy of absolute power. Example: the fall of Franco triggered by free trade. The contrair of Fidel Castro, Isn't ?

ReplyDeleteBut now some economist, Keynesians, have forget this first and simple lesson.

For example, Matt Usselmann, who put in the same level US and German Hitler's. Terrible. And what about the silly answer of Coppola? is really US as brutal as Hitler? really you tink that?

Maybe the Germans focus on hyperinflation rather than debt-deflation because the latter got Hilter elected, who knows. I doesn't really matter. What matters is that Germans pursue export-led growth. Therefore the issue is whether there should be free-trade or not. If there isn't free trade, then countries can't pursue export-led growth as easily. This however would force governments to actively intervene on building domestic capacity. That isn't much different to autarky, of which Frances seems to be dismissive.

ReplyDeleteActually export-led growth strategies are not usually compatible with free trade, since they typically involve creating barriers to incoming trade and deliberately manipulating prices and currency values to confer trade advantage. I am in favour of genuinely free trade. Unfortunately there isn't much of it in this world.

DeleteTrue, a mercantilist νation interferes against free-trade by a number of means (suppressing it's currency, suppressing domestic demand etc), but a nation that doesn't pursue export-led growth doesn't. But if there wasn't free-trade at all (i.e. if there were import tariffs), then mercantilism wouldn't amount to much. We have to be pragmatists and accept that genuinely free-trade is an impossibility, and that a system like Keynes' ICU (which would promote balanced trade) is the best solution.

Delete"For example, Matt Usselmann, who put in the same level US and German Hitler's. Terrible. "

ReplyDeleteClearly I did not say that at all. I said in the last 50 years the US has been pretty brutal when bombing its enemies. USA is not autark.

I made no comparison to the atrocities of Nazi Germany. You are clearly imagining things.

But it is stupid comments like this, Miguel, which make discussions really difficult here. It is the second time now I have to clarify something which someone imagined I have said.

Matt, please remember that English is not Miguel's first language.

DeleteNazi Germany autarkic? I doubt it. Ritschl certainly thought not and one would think he would be sympathetic to that view.

ReplyDeleteThe view that most of the Deficit spending went towards arms doesn't add up. Why were the Nazis so unprepared for war they thought would occur. Ritschl believes all of Mefo funds were so ascribed but that makes little sense.

Hitler inherited a large public works program from Schleicher which he increased. combine that with a fall in real wages and you get a recovery and full employment.

As for concentration camps i would advise you read Gellately. He has two chapters on them. One for what occurred before 1938 and another for what occurred after 1938. you are conflating the two.

concentration camps pre 1938 were temporary and most but not all people were released.

Ritschl disputes the idea that the Nazis pursued a general autarky policy as preparation for war. I, too, would dispute this. My view, supported by Ritschl's evidence, is that the Nazis were disengaging from trade with large Western powers and refocusing on smaller, more local countries with the intention of incorporating them within the renascent German empire. Autarky therefore was intimately bound up with empire building, but not necessarily with war.

Deletehttp://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/capitalisback/CountryData/Germany/Other/Pre1950Series/RefsHistoricalGermanAccounts/Ritschl01.pdf

You are rather selective in your appeal to authority. Ritschl repeatedly refers to the Nazis' hostile intentions towards their neighbours. Invasion and annexation is not easily done without superior military force. Nazi Germany may not have expected Britain to defend Poland, but it surely planned to invade Poland.

Hitler inherited a rather small public works programme, actually. Nowhere near enough to bring unemployment down so fast. However, he did expand it massively, and at least to start with the expenditure was on infrastructure not armaments. As I said, autarkic regimes don't necessarily start off brutal. They can start off populist and economically effective.

I do not conflate the two forms of concentration camp. See my reply to Matt Usselman. I clearly distinguish them. However, my point is about work ethic and the definition of "people", not about concentration camps per se.

The point of this post is that the taboos that prevent us looking with clear sight at events we remember with repugnance also prevent us learning from them. We develop a distorted view of history that leads us to make terrible policy mistakes. Hitler's real devaluation and fiscal expansion ended the Depression in Germany far more quickly than FDR's policies in the U.S. But because of what came next, we dare not say that anything Hitler did was good.

The leading German Economics Journal praised The General theory and claimed Keynes for The Reich by asserting that Hitlers policy was perfect Keynesianism. Causing keynes considerable embarrassment at the time. All sorts of policy has no natural home in a given political ideology. rather political parties and leaders take ideas as they need them. Which has the unfortunate result of associating good policy with bad regimes in many minds.

ReplyDeleteGreat set of questions Francis and much to ponder. I would be interested in how colonial arrangements played into German ambitions, government policy and economic dynamics during the period in question. The struggle for markets and resources surely played a role in German history of the period.

ReplyDelete"SCHACHT LETS THE CAT OUT OF THE BAG

ReplyDeleteLight is thrown on this mystery by the later writings of Hjalmar Schacht, the currency commissioner for the Weimar Republic. The facts are explored at length in The Lost Science of Money by Stephen Zarlenga, who writes that in Schacht's 1967 book The Magic of Money, he "let the cat out of the bag, writing in German, with some truly remarkable admissions that shatter the 'accepted wisdom' the financial community has promulgated on the German hyperinflation." What actually drove the wartime inflation into hyperinflation, said Schacht, was speculation by foreign investors, who would bet on the mark's decreasing value by selling it short.

Short selling is a technique used by investors to try to profit from an asset's falling price. It involves borrowing the asset and selling it, with the understanding that the asset must later be bought back and returned to the original owner. The speculator is gambling that the price will have dropped in the meantime and he can pocket the difference. Short selling of the German mark was made possible because private banks made massive amounts of currency available for borrowing, marks that were created on demand and lent to investors, returning a profitable interest to the banks.

At first, the speculation was fed by the Reichsbank (the German central bank), which had recently been privatized. But when the Reichsbank could no longer keep up with the voracious demand for marks, other private banks were allowed to create them out of nothing and lend them at interest as well.4

A STORY WITH AN IRONIC TWIST

If Schacht is to be believed, not only did the government not cause the hyperinflation but it was the government that got the situation under control. The Reichsbank was put under strict regulation, and prompt corrective measures were taken to eliminate foreign speculation by eliminating easy access to loans of bank-created money.

More interesting is a little-known sequel to this tale. What allowed Germany to get back on its feet in the 1930s was the very thing today's commentators are blaming for bringing it down in the 1920s – money issued by seigniorage by the government. Economist Henry C. K. Liu calls this form of financing "sovereign credit."

http://www.thefreepressonline.co.uk/news/1/1587.htm

The German did not engage in Keynesian per se' as they successfully kept consumption down when the recovery continued. This is at odds with Keynesian . Here I agree with Ritschl.

ReplyDeleteHitler overstated his arms for what reason we still are not sure of. He was in no shape to fight a European war in 1938.

Yes it wasn't a massive infrastructure program BUT combine that with a fal in real wages and wella a robust recovery no other nation had.

Frances,

ReplyDeletePlease get it through your head that there is no mercantilism in modern Germany. Pupils in school learn that mercantilism is unproductive. German export surplusses are not due to mercantilistic ideology or government pressure. The government would be quite happy if there were none.

You have absolutely no evidence for your theory except uninformed historical speculation.

" The government would be quite happy if there were none. "

DeleteNot according to this?

" They have much lower corporate tax rates than our businesses, as in most of the world, to expedite exports and enhance competition with other countries. Their government realizes the importance of their manufacturing base and legislates laws to promote exports. In some cases, such as automobiles, exports are subsidized by the government in the form of tax credits. This is all payed for by their tax payers. The reason Germany is willing to guarantee loans to some of the PIIGS countries is because as long as the Euro stays strong, German exports will be desirable. If the PIIGS ever go bankrupt, get away from the Euro and devalue their own currencies, German exports will be reduced because of price increases. "

http://pjmedia.com/spengler/2011/10/06/wall-street-protesters-have-met-the-enemy-and-it-is-they/2/

Postkey:

DeleteNone of your quote occurs in the link you give.

Any way, the quote is ill-informed: "..as long as the Euro stays strong, German exports will be desirable."

The fact is that German exports are even more desirable if the euro is weak. That's why some people object to the ECB's quantitative easing as a currency manipulation.

And the quote is clearly ill-informed about German tax law. Don't take it seriously - it was written by some self-important fool. If you think it true you must provide more convincing evidence.

Sorry about that.

DeleteI googled

"They have much lower corporate tax rates than our businesses, " and I was sent to the same site!

Corporate tax rates have nothing to do with mercantilism - or do you think Ireland is mercantilist because their tax rate is half of the German one?

DeletePostkey20 October 2015 at 09:21

DeleteYou say:

"I googled

"They have much lower corporate tax rates than our businesses, " and was sent to the same site!

I did the same and wasn't. Where did you get your quote?

Frances,

ReplyDeleteTo help you understand why the German government would be happier if there were no export surpluses (apart from reducing tensions with other countries).

The answer is:

VAT.

Under the rules of the European Union (which also apply to Britain), export sales are exempt from VAT. Imports, on the other hand, are subject to VAT. So the higher the export surplus not counterbalanced by imports, the higher the VAT payments the government has to forgo.

To give you an idea of the dimensions:

In 2014, Germany's export surplus was 7.6 % of GDP. Imports of the same dimensions would have brought the government approximately 19 %(the usual rate of VAT for imports) of that amount.

Since German GDP is around 3 (American) trillions of € (one American trillion is one million millions; in Europe they call that a billion), the VAT would be around 1.4 % of GDP, i.e. over 40 milliards (in American: billions) of €. That is about 14 % of the federal budget.

What government wouldn't like that?