Nobel laureates, halo effects and idiosyncratic markets

Chatting to a young Indonesian

economist over breakfast this morning, I discovered that

his impression of Nobel laureates had been radically changed by the

Lindau meeting.

“I used to think that being a Nobel

Laureate meant being a world expert in economics”, he said. “Now

I know that's not the case. Nobel Laureates are world experts in

their own particular area of research. But they aren't experts in

economics as a whole.”

The tendency to regard people who are

highly qualified and experienced in one area as therefore competent to pronounce upon everything

under the sun is a form of what is known as the “halo effect”. And it can have

absurd consequences. In a press briefing that I attended, a

journalist from a well-known news publication asked the American

economist Peter Diamond to comment on the Eurozone. The journalist in

question is an EU citizen resident in Frankfurt who has been

reporting on European matters for several years. She has far more

practical knowledge and experience of the Eurozone than Diamond. But

because of his Nobel laureate status, he was presumed to have

opinions on the Eurozone that were of more value than hers.

To his credit, Diamond refused to

answer the journalist's question, saying that his area of research

was entirely US-focused. But other American Nobel laureates were not

so humble.

Edmund Phelps, in a breakfast briefing

for young economists, extolled the virtues of American “opportunity”

and criticised European “corporatism”. This was in a panel

discussion on innovation sponsored by Mars, whose European

representative - sitting on the panel next to Phelps – had much to

say on innovation within large enterprises. And a young French

economist on the same panel talked about entrepreneurialism in

European countries. No matter. To Phelps, America was the source of

all innovation, and Europe had a “terrible problem”.

But Phelps actually undermined his entire argument by comparing the US with something called “Europe”. Had he compared the US with, say, Germany, it would have been a fair comparison, although I'm not sure his conclusions were justified. But directly comparing a country, even one with a federal model of governance, with a whole continent is absurd. Europe is astonishingly diverse, and although its residents do generally recognise a common identity called “European”, it does not have the strength of the “American” identity. “Europe” is still a work in progress.

Phelps's views on America and

Europe were directly contradicted the very next day by another

American Nobel laureate, Joseph Stiglitz. Here is Stiglitz –

soundbite king as ever:

The idea that America is a “land of opportunity” is a myth. It's not so much the American dream as the Danish dream, or perhaps the Scandinavian dream.

I wonder which of these august

gentlemen is right? I suspect neither. It is too easy to see America

as the source of all innovation and Europe as free-riding on

America's inventions. But equally, it is unfair to dismiss America,

which remains a vibrant individualistic culture. Such competitive comparisons are unhelpful and unnecessary.

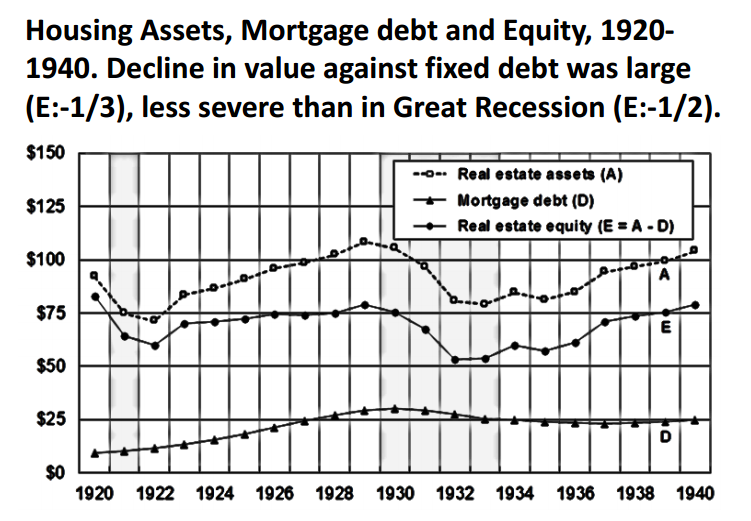

This brings me to the subject of

American dominance among economics Nobel laureates. In his presentation on the role of the housing market in the Great Recession, Vernon Smith

showed a series of extremely interesting slides. Here are a couple of

them:

The whole presentation was excellent and his conclusions important. I shall write about this separately. But there is an important omission in the header of each of these slides. And that omission is telling.

Smith was of course talking exclusively

about the American housing market. But nowhere on his slides does he

show that. The slides are simply about “the housing market”. This

was in a presentation to young economists, business and media

representatives from 80 countries.

Smith presented to this international

audience as if all housing markets everywhere were like the US and

therefore he did not need to define the boundaries of his research.

But nothing could be further from the truth. Housing markets are

astonishingly diverse, no doubt because housing is a basic survival

need and in many countries also a primary source of wealth. The US

housing market is one of the most idiosyncratic: it has unique

features such as 30-year fixed rate mortgages, warehousing and GSEs;

it has more extensive government and near-government support than

almost anywhere else; and it is as far as I know the only housing

market where the majority of mortgages are securitised. Yet Smith did

not see fit to tell his international audience that his research ONLY

applied to the US and could not be taken as a model for anywhere

else. Indeed he possibly didn't even think of that. The parochialism

of American economists is at times staggering.

Nor is it just economists who are

ignorant of national idiosyncracies in key markets such as housing. I

had an interesting discussion with an American freelance economic

journalist about the Bank of England's Funding for Lending scheme

(FLS). Under the FLS, banks can temporarily swap illiquid prime loans

(mostly mortgages) for highly liquid treasury bills, which they can

then use as collateral in repo markets, thus enabling them to obtain

market funding more cheaply. I explained this to my American friend,

and his response was “I don't think people understand

securitisation”. Umm. This scheme is not securitisation, and it

would not work in a largely securitised marketplace such as that in

the US. It only works when banks have large balance sheets made up

mostly of illiquid loans.

In most European housing markets,

lenders usually carry mortgage loans on their balance sheets rather

than securitising and distributing them, which means that as their

mortgage lending increases their balance sheets gradually become

larger and more illiquid. To an American knowledgeable about

economics and familiar with the operation of his own housing market,

this is a very strange way of doing things. Yet to a European, it is

the American way of doing mortgage lending that is odd. My American friend is

indeed correct that people don't understand securitisation. To

Europeans, it's a nasty American practice that nearly blew up the

world.

This is not unlike the “accent”

problem. I have no accent. Of course I don't. Everyone else has an

accent, not me. So when I went to the US on a business trip a few

years ago, I walked into my company's New York office, said something

and was astonished to hear from the other side of the office, “I

LOVE that accent!” It took me some time to realise that the person

they were speaking about was me. I have an English accent. Of course

I do. We do not see our own idiosyncracies.

The economics profession is dominated

by Americans, and by research that focuses on American markets and

American ways of doing things. Of 17 Nobel laureates presenting at the Lindau Economics Meeting, nearly all were elderly white middle-class male

Americans – so hardly representative even of America - and most of

them were doing exclusively American research. There is a terrible

dearth of research that looks at other markets, particularly emerging

ones: and an even greater scarcity of research that compares

idiosyncratic markets, not in the Edmund Phelps compare-to-denigrate

mode but in the interests of promoting international understanding of

different ways of doing things.

All economies have unique features,

that grow from deep historical and cultural roots: all have common

features too. The problem is disinguishing between those

characteristics that are common to all economies, and those that are

nationally or regionally idiosyncratic. When one nation is dominant

in the field of economics, a research model that narrowly focuses on

the economic features of that nation runs the risk of being

interpreted as applying to all economies, especially if that model is

developed by a Nobel laureate. Halo effects lead to “generalisation

from the particular”, and a failure to recognise and promote

understanding of economic diversity. There is no one right way of

doing things, and the American way – or any other nation's way, for

that matter – is neither universally applicable nor even necessarily the best.

Was there any discussion of the inability of economists, with all their models and Nobel Prizes, to agree on the causes of The Great Depression and The Great Recession, or fixes that work (ed) or don't /didn't? ( If physics were economics physicists would still be arguing about whether E=mc² or not.)

ReplyDeleteNo. But you've missed the point. Economics is a diverse discipline: a specialist in, say, labour market economics may have nothing useful to say about the causes of either the Great Depression or the Great Recession, though he might have a great deal to say about the persistence of unemployment AFTER those crises. Would you expect a specialist in applied mechanics under conditions of Earth gravity to comment on the trajectory of a comet?

DeletePoint taken. So the reason I should ignore what economists say on American TV is not because there is no daylight between their politics and their analyses but because they never preface an analysis with an assertion of their particular field of study? Granted, I don't think I've ever seen an interviewer ask or comment on an economist's field of expertise (with the exception of Bernanke's study of the Great Depression).

DeleteIs there, then, consensus within any particular specialty? And if there isn't, doesn't that represent a problem? (Yes, physicists still argue about lots of things, but they tend to agree on what would constitute proof. Economists can't seem to reach consensus even on past events for which a whole range of facts, numbers exist. Take Piketty, for ex.)

Maybe my basic complaint is that economists speak with the same assumption of authority as a physicist talking about the fixed speed of light in a vacuum. I never hear anything akin to "based on these assumptions, which are open to debate, and within these limits of our studies, we think/recommend ...").

Apologies for taking your post and rambling on but economic decisions by politicians around the world have huge consequences, and I've begun to wonder if less harm might be done if they simply ignored all economists or, perhaps more fairly, if their decisions would be any worse if "economics" didn't exist.

So when I read about a conference of Nobel economists who don't address the failures or limits of their discipline ...

How much of this issue boils down to lack of data? Wouldn't macroeconomists, for example, love to have a bigger sample size from models calibrated with data pooled across all G20 nations? But how many of the G20 nations were collecting reasonable economic statistics in the 1950s?

ReplyDeleteYou implicitly assume that the only nation collecting reasonable economic statistics was the US. That is also an example of US-centricity. The US is not only far from being the e only nation collecting economic statistics at that time, its records are neither the most complete nor the most accurate. France, for example, has far better data - see Piketty.

DeleteI don't think the narrow US focus of American economists has anything to do with data. I think it is their very natural and understandable preference for studying their own country - just as I have a natural tendency to write the most about mine.

It seems that the Danes got securitisation of mortgages right about two hundred years ago. Clever little country. It helps to have a high density, homogenous population with a deep shared history.

ReplyDeleteMy screen name and avatar might both suggest that I have a soft spot for things Danish. Absalon was a Danish Bishop and the avatar is a picture of a piece of Royal Copenhagen porcelain - a small boy offering to hand you a pig.

DeleteDemark's mortgage market is certainly unusual. And it seems very stable.

Delete