Lessons from the disaster engulfing Silvergate Capital

This is the story of a bank that put all its eggs into an emerging digital basket, believing that providing non-interest-bearing deposit and payment services to crypto exchanges and platforms would be a nice little earner, while completely failing to understand the extraordinary risks involved with such a venture.

On 1st March, Silvergate Capital Corporation announced that filing of its audited full-year accounts would be significantly delayed, and warned that its financial position had materially changed for the worse since the publication of its provisional results on January 17th, when it reported a full-year loss of nearly $1bn.

The stock price promptly tanked, falling 60% during the day:

Platforms, exchanges and other banks halted or re-routed transactions on Silvergate's SEN payments network, and customers that had other banking relationships removed their deposits. In response, Silvergate halted the SEN network. A banner on its website now reads:

Effective immediately Silvergate Bank has made a risk-based decision to discontinue the Silvergate Exchange Network (SEN). All other deposit-related services remain operational.

However bad Silvergate's financial position was before the announcement, it is now much, much worse. Some are questioning whether it will survive. "We believe a receivership/liquidation scenario is a distinct possibility," said analysts at Wedbush Securities (Reuters).

The proximate causes of Silvergate's distress appear to be twofold. Firstly, a demand from the Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco to repay its advances "in full", for which Silvergate has had to sell securities. Secondly, losses due to impairment of its securities portfolio. This toxic combination of circumstances threatens Silvergate's solvency:

These additional losses will negatively impact the regulatory capital ratios of the Company and the Company's wholly owned subsidiary, Silvergate Bank (the "Bank"), and could result in the Company and the Bank being less than well-capitalized. In addition, the Company is evaluating the impact that these subsequent events have on its ability to continue as a going concern for the twelve months following the issuance of its financial statements. The Company is currently in the process of reevaluating its businesses and strategies in light of the business and regulatory challenges it currently faces.

And it reveals an underlying fragility that raises serious questions about the business models of banks involved with crypto.

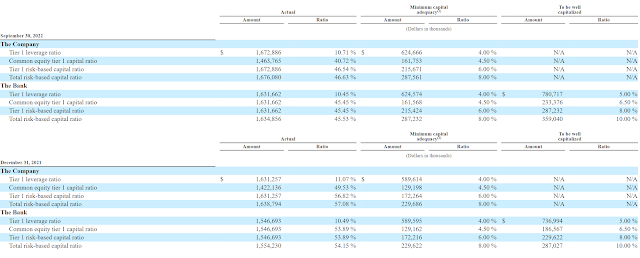

Silvergate's asset base consists largely of US treasuries, agency MBS and CMOs, and muni bonds, mostly maturing within 12 months. Many of these are zero-rated for capital purposes. Hence the extraordinarily high CET1 and Tier 1 capital ratios it reported in its interim accounts in September 2022:

But the government securities in Silvergate's asset base are exposed to market risk. In the last year, yields have risen significantly, and prices have correspondingly fallen. So the fair value of Silvergate's assets is considerably lower than it was a year ago. Silvergate's solvency was already threatened long before the bank run that drove it to its knees. Interestingly, this is reflected in its share price:

Since the fair value loss arose mainly from the Federal Reserve's interest rate rises, and the Fed had given no indication that it intended to stop raising interest rates any time soon, arguably Silvergate should have impaired these assets. But Silvergate's management thought the fall in value was only temporary:

....The Company determined that none of its securities required an other-than-temporary impairment charge at September 30, 2022.

And they believed they wouldn't have to sell any of these assets before the maturity date, so would recover the full value:

Current unrealized losses are expected to be recovered as the securities approach their respective maturity dates. Management believes it will more than likely not be required to sell any of the debt securities in an unrealized loss position before recovery of the amortized cost basis.

But they were wrong.

In November 2022, the crypto exchange FTX collapsed. Crypto depositors rushed to withdraw their funds from the crypto exchanges and platforms that banked with Silvergate. To meet those withdrawal requests, the crypto exchanges and platforms drew on their Silvergate deposits. Runs on Silvergate's customers became a run on Silvergate. Billions of dollars flowed out of its accounts. By the end of December, its total deposits had fallen by $6bn.

But Silvergate's assets were largely in the form of investment securities. So it didn't have sufficient liquidity to finance the proxy run. It had to pledge or sell securities to obtain liquidity.

Initially, Silvergate borrowed heavily from the San Francisco FHLB. The FHLB-SF was Silvergate's main source of short-term funding, though it also had credit lines with three correspondent banks and access to the Fed's discount window. At 30th September, Silvergate had outstanding advances of $700m from FHLB-SF and had pre-positioned sufficient collateral to borrow an additional $1.6bn. But provided it could stump up sufficient collateral, it could borrow up to 35% of its total assets. And it did. In the fourth quarter of 2022, it borrowed an additional $3.6bn. At the end of December, its total borrowing from FHLB-SF stood at $4.3bn, or about 29% of its total assets.

Funding from the Federal Home Loan Banks is intended to support residential real estate lending. And to that end, it is taxpayer guaranteed. Federal Home Loan Banks are government-supported enterprises overseen by the Federal Home Finance Association (FHFA).

Silvergate's use of FHLB-SF funding to facilitate a proxy run originating from crypto exchanges and platforms raised a lot of eyebrows - including, perhaps, at the FHLB-SF itself. For reasons which are not entirely clear, the FHLB-SF now seems to have either terminated the loans or declined to roll them over. Silvergate has had to pay all the money back.

We don't know exactly why the FHLB-SF pulled the funding. But it can't simply have been done on a whim, as some have suggested. A loan is a legal agreement, so if the loans were terminated, there must have been a breach of the terms and conditions.

Bank loans to commercial enterprises are typically subject to covenants that set minimum requirements for key performance indicators such as debt/assets, debt/equity or EBITDA. As Silvergate is a bank, covenants might include regulatory captal ratios such as Tier1 capital, leverage ratio or liquidity coverage ratio.

Breaching one or more covenants means loans become instantly repayable. Lenders are often willing to delay testing covenants if the company is experiencing temporary difficulties such as, in Silvergate's case, a proxy bank run. But it seems the FHLB-SF wasn't willing. It wanted its money back. Was it spooked by the disastrous fall in Silvergate's leverage ratio, from well over 10% to just a whisker above 5%, when the assets previously classified as held-to-maturity were moved to available-for-sale? Or did Silvergate inadvertently break some other rule, such as the Federal Housing Finance Association's tangible capital rule, which has attracted criticism from the American Bankers' Association for causing liquidity problems for smaller banks when interest rates rise?

Even if the FHLB-SF simply declined to roll the loans over, it would have done so because for some reason Silvergate no longer met its lending criteria. This would most likely be due to the considerable deterioration in Silvergate's financial position in the fourth quarter of 2022, but it could also have been that the FHLB-SF's supervisory bodies took a dim view of a government-sponsored home loan bank lending taxpayer-backed funds to finance a crypto-related bank run.

Whatever the reason, the FHLB-SF's action was draconian. Not only did it pull the funding, it did so with effect from the 31st December, with a short stay of execution to enable Silvergate to raise the money. Silvergate sold securities in January and February to repay the loans. These sales will be included in the 2022 full-year accounts.

But the $3.6bn Silvergate borrowed from the FHLB-SF wasn't enough to cover the massive deposit outflows in the fourth quarter of 2022 anyway. And for some reason, Silvergate didn't want to borrow from the Fed. So even before the FHLB-SF pulled its funding, Silvergate was already selling securities.

Selling securities at market price crystallized the fair value losses that had accrued over the past year, Even before the FHLB-SF pulled its funding, this resulted in a provisional headline loss of $1.1bn. The loss will be much larger in the restated full-year accounts.

Because of the securities sales, in December 2022 the bank moved all its held-to-maturity securities back to available-for sale. As a result, Silvergate will now have to impair its entire securities portfolio and take the losses through P&L as "other comprehensive income". This won't affect the headline loss, but it will negatively affect the bank's capitalization, and the impact will be considerable. In my view this change has been forced on it by its auditors. And it is this, even more than the loss of liquidity caused by the withdrawal of the FHLB-SF advances, that threatens Silvergate's future as a going concern.

The fact that Silvergate's apparently low-risk balance sheet structure has proved so fragile has important implications not only for banks and their regulators, but for crypto exchanges, platforms and stablecoin issuers.

Silvergate's crypto-related balance sheet structure was that of a money market mutual fund (MMMF). If Silvergate were a MMMF, the fall in the fair value of assets could be reflected in a lower net asset value, and customers trying to withdraw their deposits might not get their entire investment back. But Silvergate is a bank - in fact it is a member of the Federal Reserve system and has a Fed master account which gives it direct access to dollar payment services via Fedwire. Federally-regulated banks are required to honour deposit withdrawal requests at par. So the fall in the fair value of Silvergate's assets was not matched by a corresponding fall in the value of liabilities.

And this exposes the real problem with Silvergate's business model. Silvergate provides depository and payment services to crypto platforms. In September 2022, 90% of its deposits were non-interest bearing demand deposits from crypto platforms, almost all of which did not qualify for FDIC insurance. As the name implies, demand deposits can be withdrawn at any time without notice. In the classic bank run, it is demand deposits that are withdrawn. The more demand deposits a bank has, the more at risk it is of serious liquidity shortfalls in a bank run.

So up to 90% of Silvergate's deposits could be withdrawn at any time, at par, without notice. That's almost all of its funding base. And to make matters worse, the deposit withdrawals could take the form of payment requests made by customers of Silvergate's crypto platform customers to those platforms, not to Silvergate itself. Silvergate would have no control over the size or the timing of the withdrawals. It would simply have to make the payments.

Had Silvergate actually been fully reserved - by which I mean holding sufficient central bank reserves to enable all of its deposits to be withdrawn simultaneously - it would have had no problem paying out up to 90% of its deposits at par. But because Silvergate's asset base consisted largely of interest-bearing securities, it didn't have sufficient liquidity to honour such demands.To meet them, it would have to borrow from other banks, from the FHLB, or from the Fed. And if these sources failed, it would have to sell securities. But the market price of the securities could differ from their carry value. So there was a risk that selling them would fail to raise enough liquidity and/or would render the bank insolvent.

I often see crypto people describing as "fully reserved" a balance sheet that consists of deposit liabilities backed by high-quality investment securities of the kind held by Silvergate. But the disaster that has engulfed Silvergate shows that this isn't really full-reserve banking. Silvergate's deposits were backed by US government securities, and its capital ratios looked extremely healthy. But its solvency was threatened by fair value losses, and it had insufficient liquidity to meet deposit withdrawal requests. If the duration of your assets doesn't match that of your liabilities, and you don't have enough liquidity to finance a run on deposits, you aren't fully reserved.

Silvergate also resorted to some doubtful accounting tactics to conceal its fragility. It is at best unwise to mark securities as "held-to-maturity" and carry them at amortised cost when they are the backing for demand deposits and might therefore have to be sold at any time to obtain liquidity. Auditors didn't have the chance to question this until the year-end reporting cycle. But regulators did. Why didn't they intervene?

Silvergate could have opted to back its non-interest-bearing deposits fully with central bank reserves. There are still ample reserves in the dollar system, and the Fed is still paying interest on them. It's not clear why Silvergate opted for a business model that left it dangerously exposed to liquidity shortfalls and fair value losses. Crypto exchanges, platforms and stablecoin issuers at least have the excuse that they don't have direct access to central bank liquidity. But Silvergate does - and yet it didn't use it. And no-one except the traders who were shorting it seemed to notice the risks it was running. Regulators seem to have been asleep at the wheel, again.

Finally, neither banks nor regulators have paid sufficient attention to the serious danger of proxy bank runs originating from crypto platforms and exchanges. A bank swamped with direct deposit withdrawal requests can close its doors. But a bank that is intermediating payment requests from its customers' customers has no such recourse. In 2008 the Fed had to bail out the shadow banking system to prevent proxy runs destroying regulated banks. The same dynamic is now playing out in the banks that are foolishly providing banking services to crypto platforms and exchanges without full reserve backing. Silvergate is not the only one. Regulators need to intervene now, before this cancer spreads throughout the financial system.

Related reading:

What now for crypto banking? - Coindesk

Silvergate Capital Corporation SEC filings can be downloaded here.

In defense (sort of) of regulators, capital ratios for small banks have an AOCI opt-out. The call report for Silvergate shows they had the AOCI opt-out. So the security classification shouldn't have affected Tier 1 or CET ratios. It appears that AOCI opt out is allowed below $750bil total assets. As I recall, Brainard dissented from AOCI opt-out being expanded for $250-$750bil asset banks.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/SR2002a1.pdf

True, but the FHFA's tangible capital rule does not recognise the opt-out, so tangible capital according to the FHLB's calculation can be lower than regulatory capital - potentially, significantly so. That's why I think Silvergate could have breached the tangible capital rule. The note from the American Banker's Association that I linked in the post calls for the FHFA to adopt regulatory capital rules to prevent smaller banks from losing funding because of unrealised fair value losses taken through OCI.

Delete