President Trump's Triffin problem

In many eyes, President-elect Trump is a loose cannon. He says things that upset people the world over. Many of these things perhaps should not be taken too seriously - after all, he is a showman. But it would be a mistake to dismiss his rhetoric on trade. There, he is in deadly earnest - and it does not bode well either for America or for the world.

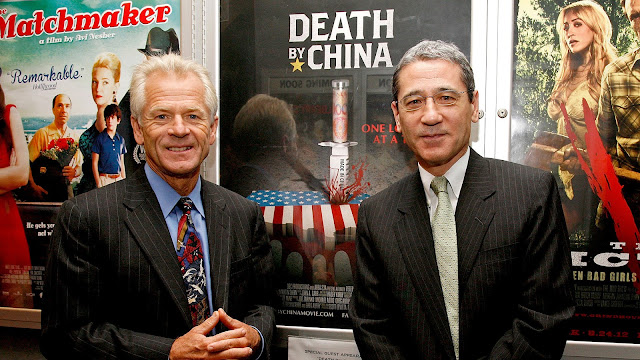

Trump's trade agenda was set out in Peter Navarro & Wilbur Ross's paper (pdf) of September 2016. Peter Navarro's most famous work is the documentary "Death By China" which essentially blames China for all America's woes. Wilbur Ross is a businessman who made a fortune from buying up and restructuring manufacturing businesses, some of them protected by George Bush's trade tariffs. Both of them are unashamedly protectionist, labelling countries running large trade surpluses as "cheaters" and "manipulators" and demanding that the rules of international trade be changed to benefit America at their expense. Both of them have been appointed to top trade jobs by Donald Trump.

Navarro & Ross identify three causes for what they describe as "America's economic malaise". Two of them - high taxation and over-regulation - are long-standing complaints by America's right-wing business community. But the third is new. Navarro & Ross explicitly blame America's trade deficit for poor GDP growth. And they claim that the trade deficit is entirely due to unfair practices by America's principal trading partners:

Trump views America’s economic malaise as a long-term structural problem inexorably linked not just to high taxation and over-regulation but also to the drag of trade deficits on real GDP growth. Trade policy factors identified by the Trump campaign that have created this structural problem include: (1) currency manipulation, (2) the equally widespread use of mercantilist trade practices by key US trading partners, and (3) poorly negotiated trade deals that have insured the US has not shared equally in the “gains from trade” promised by textbook economic theory.They name China and Germany as currency manipulators, China as the biggest "trade cheater" (i.e. mercantilist), and Canada, Mexico and South Korea as benefiting from unfair trade deals.

Many people have pointed out the gross economic errors in Navarro & Ross's analysis. At Vox, Matt Yglesias explains how imports contribute to exports: imposing high tariffs on imports simply raises business costs, reducing business profits and threatening people's jobs. The economist Greg Mankiw notes that they fail even to mention the effect on the capital account (foreign investment in America) of closing a current account deficit. Paul Krugman describes their discussion of VAT as "utterly uninformed". And Larry Summers says Trump's global economic plan is based on a "misunderstanding of how the global economy works".

I'm with Larry Summers on this. Navarro & Ross have failed to understand the nature of the US's relationship with the rest of the world. And they have therefore disastrously misinterpreted the cause of its trade deficit. There may well be currency manipulation, mercantilism and skewed trade deals. But these are not the principal cause. No, the main reason for the US's trade deficit is the US dollar.

The US dollar is the world’s premier currency for international trade and investment. More trade is done in U.S. dollars than any other currency. More trade finance is issued in U.S. dollars than in any other currency. More business investment is financed in U.S. dollars than in any other currency. Global markets price oil, metals and commodities in dollars. Even currencies are priced in dollars. The world relies on dollars to lubricate the flow of goods and services around the world.

The "quantity of money" equation MV=PY tells us that the quantity of money in circulation should be sufficient to maintain steady output. In a closed economy, when there is too much money in relation to output, there is inflationary pressure: too little, and there is risk of deflation. But because the US dollar is so widely used in the global economy, the quantity of dollars needed to support global trade far exceeds the US's productive capacity. We could say that there need to be sufficient dollars in circulation to maintain steady global output. This does not cause inflationary pressure in the US, as the equation might suggest. Rather, it creates a balance of payments problem.

How global demand for dollars creates a balance of payments problem for the US was first described by the economist Robert Triffin. Testifying before Congress in 1960, Triffin explained how the US's trade deficit was essential for the global economy, but potentially disastrous for the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system:

If the United States stopped running balance of payments deficits, the international community would lose its largest source of additions to reserves. The resulting shortage of liquidity could pull the world economy into a contractionary spiral, leading to instability

If U.S. deficits continued, a steady stream of dollars would continue to fuel world economic growth. However, excessive U.S. deficits (dollar glut) would erode confidence in the value of the U.S. dollar. Without confidence in the dollar, it would no longer be accepted as the world's reserve currency. The fixed exchange rate system could break down, leading to instability.Triffin's Dilemma, as this came to be known, played out throughout the 1960s and eventually led to the Nixon Shock in 1971, when President Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar to gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system.

From that time on, the US has been able to run persistent trade and, often, fiscal deficits without risking a damaging run on the currency. Indeed, such is the global demand for US dollars that until the era of central bank intervention and QE, the US was able to fund its growing pile of government debt at lower interest rates than any other country. The US Treasury is the world's premier savings product, and the interest rate on US T-bills is regarded as the nearest we can get to a risk-free rate in the real world.

The US's ability to obtain very large amounts of debt at very low interest rates is known as the US's "exorbitant privilege". But it could also be regarded as an "exorbitant burden". The role of moneylender to the world means the US must be a net exporter of dollars. There are two ways of exporting dollars: one is to lend them, and the other is to buy goods and services. The US does both. Its banks -including the Federal Reserve banks - lend dollars to the world, and its citizens buy imported goods and services from the world.

As this chart shows, the era of globalisation has been marked by a rapidly increasing US trade deficit.

Navarro & Ross wrongly blame this on the trade practices of other countries, failing to recognise its true origin in the US's responsibility for maintaining global dollar liquidity as global trade increased during this period. And consequently, they have come up with a policy prescription which, by closing the trade deficit, would cause a crisis of dollar liquidity, potentially leading - as Triffin warned over half a century ago - to a global contractionary spiral. We have a name for such a spiral. It is called a Depression.

I suppose Trump and his team of voodoo economists would say that they don't care if the rest of the world goes into a Depression, as long as America is ok. But there is no way that America could be insulated from the effects of such a severe global monetary contraction. To show this, we have to look at how such a monetary contraction would play out.

In the first stage, banks lend less to the world. In fact, this has been happening ever since the financial crisis of 2008. Tighter capital requirements mean banks are effectively penalised for lending to higher risks: this is causing a credit crunch for businesses (pdf), especially small and medium size enterprises and particularly in developing countries. In part due to banks' reluctance to provide trade finance, and in part due to poor demand in developed countries, global trade volume has declined significantly since 2008, though a rising dollar has helped to maintain global trade value:

(chart from David Stockman)

The US's trade deficit has already reduced significantly, which indicates that there are fewer dollars in circulation than there used to be.

For much of the period since the 2008 financial crisis, the Federal Reserve's QE programme maintained or even increased global dollar liquidity. But that is now ended, and the Federal Reserve is progressively raising interest rates. This has the effect of tightening global monetary conditions. In response to this, the dollar's exchange rate is rising.

A rising dollar exchange rate makes America's exports less competitive and encourages imports. This is entirely the opposite of what Navarro & Ross want: they want to reduce imports and increase exports. So, to the next stage of the process. To counteract the effect of the rising dollar, businesses are penalised for importing, and citizens pay higher prices for imported goods because of those penalties. What effect does this have?

Clearly, America's imports would fall, reducing the trade deficit. This is of course exactly what Navarro & Ross want. But the flip side of reducing the trade deficit is global dollar liquidity shortage (and, as Mankiw pointed out, a squeeze on foreign investment in the US). This would reveal itself as a sharply rising dollar exchange rate, especially in relation to the currencies of developing countries. If the Federal Reserve did nothing to counteract it, then the effect of the Trump team's protectionist measures would be to put upwards pressure on the dollar, impeding America's exports.

The worsening global dollar liquidity shortage would force China and other holders of US Treasuries to sell down their holdings. Such sales would be likely to raise yields on USTs, to which the Fed would most likely respond by raising the Fed Funds rate. So the tightening effect of the rising dollar could be compounded by faster monetary tightening from the Fed.

Closing the trade deficit when the dollar is rising would require progressively harsher trade controls - larger penalties for importers, price rises for citizens, perhaps outright import bans for some products. Because restricting imports raises costs for businesses, we would start to see business failures, resulting in falling GDP and rising unemployment. This is exactly the opposite of the effect that Navarro & Ross claim that closing the trade deficit would have.

Not that they would succeed in closing it, though. Other countries would inevitably respond to America's protectionist measures by imposing tariffs on American goods and services. This, in addition to the rising dollar, would make America's exports prohibitively expensive. So the effect of Navarro & Ross's protectionism would be a severe contractionary spiral in global trade, with America at the epicentre. It is not hard to imagine what the effect on the American economy would be.

It is, of course, possible to close a trade deficit by initiating a severe recession. Indeed, it is probably the ONLY way of unilaterally closing a large and persistent trade deficit. Navarro & Ross's protectionism would not improve prosperity in America. On the contrary, it would be a severe economic decline, perhaps even another Depression. And as always, the worst hit would be the working poor - the very people who voted for Mr. Trump in the hopes of a better life.

Related reading:

Safe assets and Triffin's dilemma

When populism fails, tragedy prevails - Manchester Policy Blogs

Image from the LA Times.

I am no more than a casual observer of how the world economic system works. But I am a deeply interested, close observer of America's political system. It is not surprising to me that Trump and his cronies are wrong in their analysis and their proposed policies. But I am often surprised that there are so many people who think like Trump. Where do they come from? Are they taught to think like Trump in our schools and universities, in our churches, or are they products of evolution by natural selection? If they are the latter, I wonder how rapidly they are diverging from the norm, or are the people who think like Trump already in the majority? I have often heard it said by American politicians that if America should be destroyed, it will come from within. Maybe now is the time.

ReplyDeleteI make these comments as a non-economist!

ReplyDeleteA current account deficit means that a national economy is spending more abroad than it is earning abroad out of normal operations. In short: it is living beyond its means.

A current account deficit also means that an amount equal to the deficit must flow back into the national economy either as loans or as investment from abroad. That's mathematics and not economics.

Finally, an annual current account deficit represents nothing other than the transfer of domestic wealth into foreign ownership; domestic assets become owned by foreign investors. The return on those assets goes abroad and further depresses the current account.

My understanding is that, since the Vietnam War, the US has uninterruptedly recorded enormous annual current account deficits, sometimes above 6% of GDP. The US economy has lived beyond its means. If one party lives beyond its means, another party earns beyond a normal level.

I conclude that, for decades now, growth in the rest of the world has, to a significant degree, been a function of Americans' living beyond their means. Yes, this has worked well for all sides because the squanderers could issue squanderbucks to the thrifters because the squanderbucks happened to be the world's reserve currency (Warren Buffett).

Be that as it may, I fail to see how - in the long term - a world economy which rests on the fact that one party overspends and finances that with the savings of the other parties, how such a system can be considered healthy. In fact, I don't really see how such a disequilibrium can survive in the long term. Perhaps not while we are alive but certainly after we are dead.

«since the Vietnam War, the US has uninterruptedly recorded enormous annual current account deficits, sometimes above 6% of GDP.»

DeleteThat "butter and guns" war was certainly a factor, but if you notice the first serious dip start 1980s, and the second much larger fall starts 1995. If one looks at the same 1950-2015 period for *private* debt and amount of stock traded on margin there are the two same inflection points.

In 1980 R Reagan became president and was re-elected on a massive debt and deficit fueled boom, and in 1994 N Gringrich's "Contract on America" and the Republicans retook control of Congress for the first time since the New Deal.

The Republicans have been the party of deregulation of finance, that is of bigger debt and leverage, of "wildcat" banking, of huge asset booms. Post 1980 and especially post 1994 the clintonite New Democrats decided to align their policy deregulation of finance, on bigger debt and leverage, on "wildcat" banking, on huge asset booms too; the FOMC cannot be the "loyal opposition", especially when headed by republicans, and if both parties agree on a massive debt boom, the FOMC will deregulate private banks and finance it.

Already in 1954 JK Galbraith wrote in "The Great Crash 1929" wrote:

«Just as Republican orators for a generation after Appomattox made use of the bloody shirt, so for a generation Democrats have been warning that to elect Republicans is to invite another disaster like that of 1929. The defeat of the Democratic candidate in 1952 was widely attributed to the unfortunate appearance at the polls of too many youths who knew only by hearsay of the horrors of those days. It would be good to know whether, indeed, we shall some day have another 1929.“

«how such a disequilibrium can survive in the long term»

It is indeed unsustainable, because Republican/New Democrat policy is in effect a policy of asset stripping. But as long as the asset stripping lasts the sponsors of both parties can become fantastically wealthy.

An interesting post Frances, but I am inclined to agree with kleingut. I am always astounded that most economists and politicians think inward investment (which is an inevitable consequence of a current account deficit) is a good thing. It is not. It is debt-financed consumption and a sell-off of national assets. Countries like the USA and UK don't need other people's money to fund investment. We can always print our own. The only inward investment we need is in the form of skills and technology, people and ideas.

ReplyDeleteI am also not convinced by the Triffin argument either. Yes it is true that the dollar is the world's reserve currency and that trade in dollars lubricates world trade. But it doesn't follow that there needs to be a steady increase in dollars exported from the US to facilitate this. Just as in a normal economy, if the economy expands any expansion can be accommodated by an increase in the velocity of circulation of money without a need to increase the money supply. Even if the money supply does increase it should only increase in line with global GDP growth and that money will end up mainly as currency reserves in other central banks. But the corollary is the Fed should also need a growing foreign currency reserve of its own, so the two should at least partially cancel.

I think there is another point that economists have failed to appreciate: the link between a government's budget deficit and its current account deficit. I think it is the former that drives the latter to a large degree because a large part of the deficit is funded from the overseas bond market. It would therefore be interesting to see what would happen if the US and UK governments funded their deficits entirely from money printing at the central bank with variable limits on their maximium annual overdraft set by an inflation target. In other words move towards some form of QE or MMT and cut out the bond market. I suspect that would massively reduce the current account deficit and allow both currencies to find their correct value on the currency markets.

I don't agree with any of this.

DeleteThere is no difference in monetary terms between funding by issuing debt and funding by printing money. All debt issuance does is act as a brake on the inflationary effect of money printing. I have explained this many times.

The USA does not use other people's money to fund investment. It uses its own money, which leaves the country through the current account and is returned to it through the capital account. No other country can create dollars.

It is ridiculous to argue that FDI does not add value to the economy. The evidence that it does is overwhelming. What do you think the Toyota, Nissan and BMW factories in the US are - you know, the ones that employ thousands of people? They are FDI. I think you are confusing FDI with hot money inflows. Those, I agree, can be unproductive and damaging. But to say all inward investment is pointless is simply wrong.

Your "fixed money supply, increased velocity of money" argument is voodoo economics. The reality is that if you fix the money supply while production is increasing, the price of money rises. That is reflected in a rising exchange rate (the external price of the currency rises) and deflation (the domestic price of the currency rises). You have no reason whatsoever to assume that the velocity of money would increase unless there were exchange controls preventing the exchange rate from rising. That, of course, is currency manipulation.

I wholly disagree that the US's current account deficit is driven by its budget deficit. Because of the supremacy of the dollar in global trade, the causation is the other way round.

Money printing does not eliminate a government deficit. It simply funds the deficit. And in the absence of any means of controlling the cost of funding that deficit, it is inflationary unless production increases to mop up the additional money. Not even the US can pretend that inflation does not matter in an MMT system.

"There is no difference in monetary terms between funding by issuing debt and funding by printing money. All debt issuance does is act as a brake on the inflationary effect of money printing."

DeleteI agree, but only in a closed economy. And in a closed economy government deficits are just another form of taxation. And as I pointed out here (http://cantab83.blogspot.co.uk/2016/08/mmt-vs-bond-market.html) governments that owe money only to their own citizens can never go bust (compare Japan and Greece) because they can always tax those they owe money to in order to pay back the money that they owe. The problem is overseas debt and as I pointed out in the link above this can lead to sovereign default, and it is also deflationary and boosts the exchange rate, neither of which a country wants in a recession.

"The USA does not use other people's money to fund investment. It uses its own money, which leaves the country through the current account and is returned to it through the capital account. No other country can create dollars."

DeleteAnd a foreign currency flows in the opposite direction. The net result is that both currencies end up at their point of origin but in the meantime the US has in effect mortgaged a wealth-generating asset for goods designed for consumption. So it is now in debt and it has to pay interest on that debt and that interest will leave the US economy every year from now on.

If a country uses borrowing from overseas to finance consumption like this then it comes at a cost. In the long term it will lead to increased foreign ownership of assets, a steadily increasing capital outflow of money and profits that is denied to that country's economy, and this will reduce living standards and growth in the future compared to where they might be otherwise. In that sense it is no different to an individual using their credit card to fund a lifestyle that would otherwise be beyond their income. In the future they end up paying interest that reduces their net income.

"What do you think the Toyota, Nissan and BMW factories in the US are - you know, the ones that employ thousands of people? They are FDI. I think you are confusing FDI with hot money inflows. "

DeleteI tried to distinguish between hot money and intellectual property based investment. Toyota, Nissan and BMW are a benefit to the US because of the IP they bring and the technological advantage, not the money, otherwise they would be just displacing domestic producers. The FDI that I was arguing against were infrastructure projects paid for by sovereign wealth funds, as well as foreign investment in real estate.

"Money printing does not eliminate a government deficit. It simply funds the deficit."

DeleteI didn't say it will eliminate the government deficit. I said it would eliminate the current account deficit. The government would still be in debt but the debt would be owned by the central bank not external creditors.

I also didn't claim that it wouldn't be inflationary. It would, but in a recession you need inflation to drive up consumption and erode the real value of debt. But the effect of MMT is not to create inflation. That only happens when the economy is operating at maximum output. Money printing first creates demand. That drives a growth in output. So it provides an economy with the escape velocity to escape from recession more quickly. It is only when the economy is at full employment that it becomes inflationary. But if you have an inflation target it can then be used to rein in the government deficit during an economic boom. This of course cannot happen with debt financing via the bond market because that is inherently deflationary. So it encourages government borrowing in the boom years and hinders it in a recession as I point out here:

http://cantab83.blogspot.co.uk/2016/08/mmt-vs-bond-market.html

That is undesirable on both counts.

The US is at no risk of sovereign default. Most of its debt is owned by its own citizens. The interest on debt owned by its own citizens goes to those citizens. It never leaves the economy. And I remind you that the US benefits in other ways from dollar supremacy. Even with the interest payments on the proportion of debt that is overseas owned, the economic benefits to the US of dollar supremacy outweigh the costs.

DeleteThere is no way money printing can eliminate a current account deficit. Roughly speaking, the current account deficit consists of the excess value of imports over exports, plus the excess of investment returns to foreigners over foreign investment returns to domestic residents, plus remuneration of overseas employees. The current account deficit is not government debt, though it may include some government liabilities. The current account deficit is "funded" by the capital account, which consists of the net inward investment flows into the country, both public and private sector. When there is a current account deficit, there is always a corresponding capital account surplus. This is an accounting identity. Central bank money printing cannot change this identity, since it reflects the flows of trade and investment in and out of the economy - both private and public sector.

Please don't lecture me about money demand. The example you give is suitable for a small closed economy,not the world's largest economy and the issuer of the world's premier settlement currency. Where the US is concerned, you really have to consider the global effects. As I explained in the piece, because of the US dollar's supremacy in international trade, "maximum output" for the US is GLOBAL maximum output. Money created by the US (for this purpose I include QE, though technically this is not money printing) does not only affect the US economy. It affects the entire global economy. That is the point of this piece. Insufficient dollars in circulation globally causes international trade to shrink.

Attempting to close the US's trade deficit quickly would create a global economic winter, and the worst affected would be the US. The last time America attempted protectionism on the scale that would be needed to close this trade deficit, the result was the deepest Depression in recorded history.

Frances, I'm not disagreeing with your original post and your critique of Navarro & Ross's flawed solution to the trade deficit problem, although I do agree with them that current account deficits do reduce growth. I am disagreeing with a position that seems to suggest that trade deficits, and the US deficit in particular, are never a problem. Even Paul A Samuelson (1970 Nobel laureate) disagrees with that:

Delete"Be not misled. So strong and irreversible are America's balance of payments deficits, we must accept that at some future date there will be a run against the dollar. Probably the kind of disorderly run that precipitates a global financial crisis."

http://en.people.cn/200512/26/eng20051226_230852.html (2006)

I am merely proposing that there may be other better ways of tackling trade deficits than imposing trade barriers. And one way may be to restrict who buys government debt.

You say the current account deficit is not government debt, but I say a sizeable proportion, 30%-50% is. So about a third to a half of the current account deficit is accounted for by overseas sales of government debt. That is true for both the US and the UK. So my question is, what would be the effect of a government funding its budget deficit from money printing or borrowing directly from the central bank rather than from overseas investors? Capital flows into the country would fall, demand for its currency would fall, so the exchange rate would fall, imports would fall and exports would increase. Nothing would stay the same and so neither would the current account deficit.

Yes there could be other complications. Inflation may rise so interest rates may rise. That may suck in overseas deposits into the banking system and cause the exchange rate to rise again. Nevertheless, I think that this is a legitimate question to ask. On the other hand simply saying that, because the current account deficit is balanced by the capital account, that means that everything is hunky dory, that is not something I can agree with.

I did not say that trade deficits were not a problem. Please do not read into my post things that are not there. My criticism is of the stated intention to close the trade deficit by means of protectionist measures. I consider this to be highly damaging.

DeleteI do not think restricting government debt would have the effect you think. The current account deficit reflects the world demand for dollars. That isn't going to change if USTs are scarce. All it will do is raise their price and encourage people to hold cash dollars instead.

For what it is worth, I do not think the US's current account deficit deserves the attention it is getting. It has shrunk considerably since 2008 and is currently about 2.7% of GDP, which is frankly peanuts.

I also disagree that current account deficits are a drag on growth. The evidence says otherwise. Current account deficits are bad for emerging economies because of the risk of a sudden stop. But the inward investment they bring promotes growth. The US is at zero risk of a sudden stop. The shock horror stuff about its current account deficit is frankly scaremongering.

Kleingut, the term "living beyond its means" is meaningless for a country. It is moralising, frankly - and economics is not a morality play. Imports and exports are not distinct from each other: exports are fashioned from imports, and in turn imports include intermediate exports. Supply chains are no longer simple. So any policy that impedes imports ALSO impedes exports. It is not possible to close a trade deficit solely by protectionist measures designed to flatter exports and impede imports. What happens is that international trade falls, both imports and exports, and the country ends up materially poorer.

ReplyDeleteThe fact is that the world needs an international settlement currency. In the very distant past that function was fulfilled by gold. Under the Bretton Woods system, the US dollar was a proxy for gold. When the link between the US dollar and gold was broken, the US dollar replaced gold as the international settlement currency. ALL the countries in the world benefit from the US dollar being the international settlement currency, and the USA benefits more than any other country. That is what Trump proposes to throw away. The world would eventually find a replacement - perhaps the SDR, or the Euro. But the USA will never recover the advantage that being the producer of the world's international settlement currency confers. It is the USA, not the world, that will suffer from these policies.

I think anyone who has lived in an emerging economy and observed how foreign spending exceeded foreign revenues on a sustained basis, to be financed with foreign debt, and who has seen what happens once sudden stop occurs, any such person would be convinced that "living beyond one's means" is definitely not meaningless for a country. See Greece, for only one.

DeleteI would argue that while a state works opposite to a family, a national economy works exactly like a family in its cross-border transactions. If a family spends more than it earns, it needs to borrow or make an inheritance. If a national economy overspends cross-border, it also needs to borrow or make the equivalent of an inheritance (FDI). Just as simple as that. It could well be that the Americans won't mind if all of Manhattan, half of Florida and most of the US corporations are owned by foreigners. But maybe they will mind when things become excessive.

Do me a favor and read Warren Buffett's little tale. He really nails it.

https://klauskastner.blogspot.co.at/2011/11/warren-buffetts-simple-wisdoms.html

The USA is not an emerging economy. Comparisons with emerging economies are entirely inappropriate.

DeleteNational economies do not act like families. Not even in cross-border transactions. That is far too simplistic a view of the complex web of international supply chains. It really is not "just as simple as that".

I totally agree that it is not "just as simple as that". Neither do I think that the answer to significant current account deficits is to impose tariffs. More practical answers would be to get surplus countries to buy more from the US, to have the citizens of surplus countries spend all their vacations in the US (or sort of), etc.

DeleteI recommend watching the 2.35 min video from the 1992 presidential campaign where Ross Perot coined that phrase of a "giant sucking sound of jobs going South". 25 years later we know that he was right.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rkgx1C_S6ls

Regardless how complex trade and the supply chains are, at the end of the day there is a Balance of Payments where one line reads "current account deficit" and the other reads "capital account surplus". The former correlates with job exports and the latter with capital imports.

I think the concerns one should have about the structural German surpluses are the same that one should have about structural deficits because, be it a surplus or deficit, if they are out of the ordinary and sustained, the distort balances, they create disequilibria. I recently read "The end of alchemy" by Mervyn King. He talked a lot about these disequilibria which he viewed as the greatest threat to the world economy.

I completely agree about the German surplus. But short of ending the euro, I don't think it is possible to rebalance this. Navarro & Ross are right that Germany's surplus to a large degree arises from the weakness of the periphery Eurozone countries, and the euro straightjacket prevents them from recovering.

DeleteIsn't Germany strong government intervention in the housing market to keep housing costs down (rent controls, subsidies for new construction, and the threat of compulsory purchase to keep landowners from holding out for too high a price) one reason for the Eurozone imbalances, as it means that the savings of German householders inflate property bubbles in the Eurozone periphery as they cannot do so in Germany itself?

DeleteTo use Paul Krugman's terminology (which he developed for the United States) the Eurozone periphery is "Zoned Zone" while Germany is "Flatland" – albeit for a very different reason from red-state America, where housing is cheap due to extremely low urban densities (< 1000/sq km).

If there were global dollar tightness, would not the Euro quickly fill the gap? Low interest rates. Lots of savers.

ReplyDeleteThen the Eurozone would need to run a current account deficit. That might not be acceptable.

DeleteFrances,

ReplyDeleteYou mention several times that the US benefits from being the world reserve currency issuer, but not how.

How does the US benefit from being the reserve currency issuer?

I did say how.

Delete"From that time on, the US has been able to run persistent trade and, often, fiscal deficits without risking a damaging run on the currency. Indeed, such is the global demand for US dollars that until the era of central bank intervention and QE, the US was able to fund its growing pile of government debt at lower interest rates than any other country. The US Treasury is the world's premier savings product, and the interest rate on US T-bills is regarded as the nearest we can get to a risk-free rate in the real world."

"The US's ability to obtain very large amounts of debt at very low interest rates is known as the US's "exorbitant privilege"."

I see. And that does benefit the US, in aggregate, nominally. By which, I mean that some people in the US get things cheaper, and other people have less work, and thus less income. The difficulty is, that the number of USA citizens who perceive themselves as being negatively impact is less than the number who see themselves as positively impacted. So while it may be a net benefit nominally, a democratic society without redistributive taxes is going to view it negatively.

DeleteOr, to put it less gently, this was a cause for Trump's election. Personally, I would forgo the benefits to not have Trump. But really, does it matter? I mean, are continuing deficits that would need to grow faster than the US economy really sustainable?

I'm sorry, Frances, could you elaborate how continuous US trade deficits aren't a transfer of wealth abroad and harmful for the domestic economy?

ReplyDeleteBut yes, I agree that the rest of the world is going to miss these US deficits.