The Great Greek Bank Drama, Act II: The Heist

The banks are re-opening, though just for transactions, so people can pay their bills and their taxes, pay in cheques, that kind of thing. The cash withdrawal limit has been changed to a weekly limit of 420 EUR per card per person, enabling households to manage their cash flow better. But the capital controls remain: money cannot leave the country without the agreement of the Finance Ministry. And the banks remain short of cash: although the ECB has raised the funding limit by 900m EUR, that only amounts to about 80 EUR per Greek so won't go very far. But the tourist season is in full swing, and tourists have been advised to bring cash into the country rather than using ATMs in Greece. On balance, therefore, Greece's monetary conditions should be easing.

But there is another tranche of bailout conditions to be agreed by the Greek Parliament by Wednesday 22nd July:

Yet now, eight months later, sufficient damage has apparently been done to Greece's banks to render them collectively insolvent. What on earth has gone wrong?

Greece's banks have suffered a continual deposit drain since the beginning of the year. This is how they became dependent on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) funding from the Bank of Greece. But liquidity shortfalls do not cause insolvency unless they are covered by means of asset fire sales. In this case, the liquidity drain was until 28th June covered by ELA. Collateral has to be pledged for ELA funding, and Greek banks consequently found their balance sheets becoming more and more encumbered. To make matters worse, the ECB recently increased collateral haircuts for Greek banks. Now the banks are reopening, it is not clear how much collateral they have left for ELA funding. Whether the ECB will relax collateral requirements to allow a wider range of assets to be pledged remains to be seen. It is probably conditional on good behaviour by the Greek sovereign.

But it is not the funding side of Greek banks that is the real problem. It is the asset base.

Greece went into recession in Q4 2014 (yes, BEFORE Syriza came to power). Since then, there has been a considerable fall in output caused mainly by lack of confidence. On top of this, the Greek sovereign has been running substantial primary surpluses all year in order to maintain payments to creditors in the absence of bailout funding. It has done this not by collecting more taxes but by a considerable squeeze on public spending: this has mainly taken the form of delaying payments to the private sector. Additionally, the private sector itself has cut back spending and investment. The result is that real incomes have tumbled, unemployment has risen and loan defaults have increased. Non-performing loans in the Greek banking sector were already high at the beginning of the year but are now believed to have risen substantially. This is the principal cause of the possible insolvency of Greek banks.

So the bailout plan includes recapitalisation of the banks using a loan from the European Stability Mechanism. This loan would be repaid from sales of sequestered assets in the privatisation fund that also forms part of the bailout agreement (my emphasis):

1. Greek banks are currently reopening for transactions only. The cash withdrawal limit is likely to remain in place for the whole of the summer, effectively limiting Greeks' ability to hoard physical cash, and the capital controls that prevent money being moved outside the country will also remain in place.

2. The Greek government is required to fast-track through legislation to implement the European Bank Resolution & Recovery Directive in Greece. Once implemented, bank resolutions will involve bail-in of unsecured creditors.

3. In the autumn, the ECB/SSM will conduct another asset quality review of Greek banks to determine their solvency. Most estimates of the expected capital shortfall seem to be of the order of 15bn EUR without including deferred tax assets (DTAs), a form of capital extensively used in Greek banks that the ECB has already indicated it intends to phase out. If the ECB excludes DTAs from the CET1 definition, the bill would be at least double that.

4. Once the outcome of the asset quality review is known, the Greek banks will be recapitalised by the ESM. This implies use of the ESM's direct recapitalisation facility, which will not be available until January 2016. The banks would be supported by ELA until then, but the cash withdrawal limit and capital controls would remain in place to prevent cash hoarding and capital flight. So Greeks face the prospect of continuing restrictions on access to and use of funds for at least the rest of the year.

There are two significant implications of using the ESM's direct recapitalisation facility.

Firstly, ESM recapitalisation is de facto nationalisation of the banks by Greece's Eurozone creditors, bypassing the Greek sovereign. Once the banks were recapitalised and - presumably - relieved of their non-performing loans, they would be sold back to the private sector. The proceeds of their sale would go to pay back the ESM loans. The asset privatisation fund therefore implicitly includes all the Greek banks. Not many people seem to have understood this.

Secondly, the ESM's direct recapitalisation tool requires bail-in of 8% of liabilities. Silvia Merler at Bruegel explains what this would mean for Greek bank bondholders and depositors:

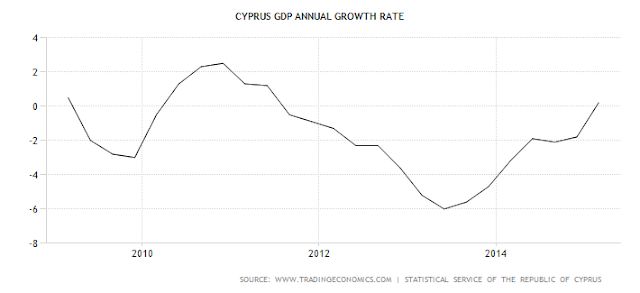

The last time uninsured deposits were haircut was the resolution of Cyprus's two failing banks in 2013. On that occasion, a reasonably large proportion of the cost was borne by foreign depositors, principally Russians, although Cypriot businesses, institutions and households also took a hit. One interesting effect of the Cyprus bail-in was that non-performing loans increased: people whose deposits were frozen were too angry to service their loans. The economic consequence of the Cypriot bank failures, including deposit bail-in, was a fall in GDP of around 6%:

But the situation in Greece is very different. Most large depositors have removed their money already. The remaining uninsured deposits - about 30% of the deposit base - are mainly the working capital of Greek businesses. Bailing these in would be far more destructive for the Greek economy than the bail-in of large depositors was for Cyprus. It is hard to put a figure on exactly what the GDP fall would be, but we should expect it to exceed the Cypriot fall by quite a bit. And this is on top of the 25% fall in GDP Greece experienced 2010-14, and a further projected 2-4% fall in GDP as a direct consequence of the output fall in the first six months of this year, and a planned fiscal tightening of 3% of GDP, and who knows how much of a collapse in the remainder of the year if cash withdrawal limits and capital controls remain in place as I expect.

Silvia argues that the working capital of Greek businesses would be exempt from bail-in because of its systemic consequences:

Bailing-in the deposits of Greek corporations and sole traders would be the clearest indication so far that restoring the Greek economy is on no-one's agenda. It amounts to a massive heist of the Greek private sector's disposable income.

I suspect Alexis Tsipras realised something like this was on the agenda, since he insisted that part of the privatisation receipts must go to new investment. But would this really be sufficient to offset the losses to Greek businesses and households of such a draconian bail-in?

The more I look at it, the less benign this bailout deal appears. Indeed it looks to me as if it was set up to do considerable damage to the Greek economy. Once this becomes apparent, Greeks are surely likely to change their minds about staying in the Euro. And I'm afraid I think this is the point. One way or another, Greece is on its way out of the Eurozone.

But there is another tranche of bailout conditions to be agreed by the Greek Parliament by Wednesday 22nd July:

The first of these is relatively uncontroversial, though a tall order to implement at the speed that the creditors demand. But the second has serious implications for Greek banks and their customers, especially in the light of this part of the bailout agreement:

- the adoption of the Code of Civil Procedure, which is a major overhaul of procedures and arrangements for the civil justice system and can significantly accelerate the judicial process and reduce costs;

- the transposition of the BRRD with support from the European Commission.

Given the acute challenges of the Greek financial sector, the total envelope of a possible new ESM programme would have to include the establishment of a buffer of EUR 10 to 25bn for the banking sector in order to address potential bank recapitalisation needs and resolution costs, of which EUR 10bn would be made available immediately in a segregated account at the ESM.

The Euro Summit is aware that a rapid decision on a new programme is a condition to allow banks to reopen, thus avoiding an increase in the total financing envelope. The ECB/SSM will conduct a comprehensive assessment after the summer. The overall buffer will cater for possible capital shortfalls following the comprehensive assessment after the legal framework is applied.Back in the autumn of 2014, the ECB & EBA conducted stress tests on European banks, including all four of Greece's large banks (which together make up about 90% of its banking sector). The Greek banks at that time passed the stress tests and were deemed solvent. They are now supervised not by Greek regulatory bodies, but directly by the ECB under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM).

Yet now, eight months later, sufficient damage has apparently been done to Greece's banks to render them collectively insolvent. What on earth has gone wrong?

Greece's banks have suffered a continual deposit drain since the beginning of the year. This is how they became dependent on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) funding from the Bank of Greece. But liquidity shortfalls do not cause insolvency unless they are covered by means of asset fire sales. In this case, the liquidity drain was until 28th June covered by ELA. Collateral has to be pledged for ELA funding, and Greek banks consequently found their balance sheets becoming more and more encumbered. To make matters worse, the ECB recently increased collateral haircuts for Greek banks. Now the banks are reopening, it is not clear how much collateral they have left for ELA funding. Whether the ECB will relax collateral requirements to allow a wider range of assets to be pledged remains to be seen. It is probably conditional on good behaviour by the Greek sovereign.

But it is not the funding side of Greek banks that is the real problem. It is the asset base.

Greece went into recession in Q4 2014 (yes, BEFORE Syriza came to power). Since then, there has been a considerable fall in output caused mainly by lack of confidence. On top of this, the Greek sovereign has been running substantial primary surpluses all year in order to maintain payments to creditors in the absence of bailout funding. It has done this not by collecting more taxes but by a considerable squeeze on public spending: this has mainly taken the form of delaying payments to the private sector. Additionally, the private sector itself has cut back spending and investment. The result is that real incomes have tumbled, unemployment has risen and loan defaults have increased. Non-performing loans in the Greek banking sector were already high at the beginning of the year but are now believed to have risen substantially. This is the principal cause of the possible insolvency of Greek banks.

So the bailout plan includes recapitalisation of the banks using a loan from the European Stability Mechanism. This loan would be repaid from sales of sequestered assets in the privatisation fund that also forms part of the bailout agreement (my emphasis):

So, let's put this jigsaw puzzle together.

- to develop a significantly scaled up privatisation programme with improved governance; valuable Greek assets will be transferred to an independent fund that will monetize the assets through privatisations and other means. The monetization of the assets will be one source to make the scheduled repayment of the new loan of ESM and generate over the life of the new loan a targeted total of EUR 50bn of which EUR 25bn will be used for the repayment of recapitalization of banks and other assets and 50 % of every remaining euro (i.e. 50% of EUR 25bn) will be used for decreasing the debt to GDP ratio and the remaining 50 % will be used for investments.

1. Greek banks are currently reopening for transactions only. The cash withdrawal limit is likely to remain in place for the whole of the summer, effectively limiting Greeks' ability to hoard physical cash, and the capital controls that prevent money being moved outside the country will also remain in place.

2. The Greek government is required to fast-track through legislation to implement the European Bank Resolution & Recovery Directive in Greece. Once implemented, bank resolutions will involve bail-in of unsecured creditors.

3. In the autumn, the ECB/SSM will conduct another asset quality review of Greek banks to determine their solvency. Most estimates of the expected capital shortfall seem to be of the order of 15bn EUR without including deferred tax assets (DTAs), a form of capital extensively used in Greek banks that the ECB has already indicated it intends to phase out. If the ECB excludes DTAs from the CET1 definition, the bill would be at least double that.

4. Once the outcome of the asset quality review is known, the Greek banks will be recapitalised by the ESM. This implies use of the ESM's direct recapitalisation facility, which will not be available until January 2016. The banks would be supported by ELA until then, but the cash withdrawal limit and capital controls would remain in place to prevent cash hoarding and capital flight. So Greeks face the prospect of continuing restrictions on access to and use of funds for at least the rest of the year.

There are two significant implications of using the ESM's direct recapitalisation facility.

Firstly, ESM recapitalisation is de facto nationalisation of the banks by Greece's Eurozone creditors, bypassing the Greek sovereign. Once the banks were recapitalised and - presumably - relieved of their non-performing loans, they would be sold back to the private sector. The proceeds of their sale would go to pay back the ESM loans. The asset privatisation fund therefore implicitly includes all the Greek banks. Not many people seem to have understood this.

Secondly, the ESM's direct recapitalisation tool requires bail-in of 8% of liabilities. Silvia Merler at Bruegel explains what this would mean for Greek bank bondholders and depositors:

Bail-in would require full haircut of subordinated/other bonds, full haircut of senior non-guaranteed bonds and still a haircut of uninsured deposits ranging between 13% and 39% for three out of four banks. This would already bring all banks above the 4.5% CET1 threshold and two of the banks above 8% CET1. The remaining capital shortfall would be covered by the ESM and Greece together, but the Greek contribution could be suspended. The ESM would effectively play only a very limited role.Silvia discusses an alternative, ESM direct recapitalisation with bail-in according to amended State Aid guidelines, which would mean bail-in of junior bondholders only:

The amended State aid guidelines require only bail-in of junior debt in the transition to the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD). After a 100% haircut on subordinated/other non-senior debt, the banks’ CET1 would still be below 4.5% in some cases. Under the ESM direct recap’s priority ranking, Greece needs to bring the banks to 4.5% CET1 before the ESM steps in and take them to 8%. With a conservative DTAs assumption, the contribution to reach 4.5% could be substantially bigger than the ESM contribution for those banks that are less capitalised and that do not have much bail-in-able junior debt. However, this contribution could be suspended by mutual agreement in light of the fiscal situation of Greece. If so, the ESM would play a more meaningful role.I'm afraid I don't think this second alternative is likely. The creditors are in no mood to cut Greece any slack, and the fact that steps are being taken to ensure that deposits don't leave the banking system in any quantity suggests that the intention is to bail them in. If I am right, then the potential economic outcome is terrible for Greece.

The last time uninsured deposits were haircut was the resolution of Cyprus's two failing banks in 2013. On that occasion, a reasonably large proportion of the cost was borne by foreign depositors, principally Russians, although Cypriot businesses, institutions and households also took a hit. One interesting effect of the Cyprus bail-in was that non-performing loans increased: people whose deposits were frozen were too angry to service their loans. The economic consequence of the Cypriot bank failures, including deposit bail-in, was a fall in GDP of around 6%:

But the situation in Greece is very different. Most large depositors have removed their money already. The remaining uninsured deposits - about 30% of the deposit base - are mainly the working capital of Greek businesses. Bailing these in would be far more destructive for the Greek economy than the bail-in of large depositors was for Cyprus. It is hard to put a figure on exactly what the GDP fall would be, but we should expect it to exceed the Cypriot fall by quite a bit. And this is on top of the 25% fall in GDP Greece experienced 2010-14, and a further projected 2-4% fall in GDP as a direct consequence of the output fall in the first six months of this year, and a planned fiscal tightening of 3% of GDP, and who knows how much of a collapse in the remainder of the year if cash withdrawal limits and capital controls remain in place as I expect.

Silvia argues that the working capital of Greek businesses would be exempt from bail-in because of its systemic consequences:

BRRD foresees some exemptions concerning bail-in, which the ESM direct recap does not have at the moment. Article 43(3) of the BRRD directive provides four exceptions, stating that in those cases the resolution authority may exclude or partially exclude certain liabilities from the application of the write-down or conversion powers. One of these exemption is when “the exclusion is strictly necessary and proportionate to avoid giving rise to widespread contagion, in particular as regards eligible deposits held by natural persons and micro, small and medium sized enterprises, which would severely disrupt the functioning of financial markets, including of financial market infrastructures, in a manner that could cause a serious disturbance to the economy of a Member State or of the Union”. This is evidently happening at the moment in Greece, where a full-fledged bank run is being kept contained only because of capital controls (which should unquestionably qualify as a “severe disruption of the functioning of financial markets”).I'm afraid I disagree with Silvia. The existence of capital controls eliminates contagion and makes it possible to bail-in deposits that would normally be considered to have systemic consequences. Provided that cash withdrawal limits and capital controls remain in place until bail-in, therefore, there should be no destabilising effects on financial markets or financial market infrastructures. And apparently the microeconomic foundation of the economy can be destroyed with impunity as long as financial stability is not threatened. So therefore I think that bailing-in large deposits and senior unsecured bonds as well as junior debt is exactly what the creditors have in mind.

Bailing-in the deposits of Greek corporations and sole traders would be the clearest indication so far that restoring the Greek economy is on no-one's agenda. It amounts to a massive heist of the Greek private sector's disposable income.

I suspect Alexis Tsipras realised something like this was on the agenda, since he insisted that part of the privatisation receipts must go to new investment. But would this really be sufficient to offset the losses to Greek businesses and households of such a draconian bail-in?

The more I look at it, the less benign this bailout deal appears. Indeed it looks to me as if it was set up to do considerable damage to the Greek economy. Once this becomes apparent, Greeks are surely likely to change their minds about staying in the Euro. And I'm afraid I think this is the point. One way or another, Greece is on its way out of the Eurozone.

Thank you. A very informative blog entry.

ReplyDeleteThe four research reports I have read (RBS, Morgan Stanle, Citi, Auto) assessing Greek bank liabilities and likely restructuring, range in the potential implications for depositors. I personally agree with the scepticism of your assessment and have to agree that judging from prior conditions and the effects on the Greek economy - serious concerns are entirely justified.

I understand Germany and Spain have both submitted draft laws/bills intending to define country specific rules on the composition of the BRRD Liability Stack. The similarity between the two models would imply little room for the peculiarities of Greek banking under the regulation. Additionally, both models place Corporate Deposits in the deluge 'waterfall of loss absorption' before Retail and SME deposits, which are in the most protected position. I suspect bigger corporations will end up the winners.

According to the reports I mention, it appears, for Retail and SME depositors, there could be exposure of up to 40% of deposits over 8,000 Euros. This would be dreadful. However, as you mention the banks' balance sheets are really very different; Alpha bank appears in relatively much better shape, whereas Eurobank is in the least desirable position. I wonder how the liabilities between the four banks will be distributed in the final restructuring. For some Greek savers this would be the second time their savings have taken a haircut; and of course the nationalised banks will be sold not to replenish the state coffers but to satisfy the appetites of European officials who continue to work under clearly delirious notions.

This does not look good for anyone, nor the image of the Euro in Greece. Since arriving in Athens it's clear the Euro is already much less popular than it used to be. The intended manufacture of a bitter split from the Euro might well drive a highly punitive approach to the restructuring. Clearly this is debt no one wants to own (and debt no one has to own incidentally, given the Eurozone's penchant for Special Purpose Entities).

Sean @papertrilby

In general, I think at this point, much of the blather about the euro currency's "popularity" is effectively mere propaganda, to be dismissed in favor or more nuanced assessment of a community's opportunities and affordances when it comes to being able to manage (let alone *like*) a currency.

Delete"ESM recapitalisation is de facto nationalisation of the banks by Greece's Eurozone creditors".

ReplyDeleteSo I guess the WSJ was right and shareholders can expect their entire equity to be wiped out...

I wonder how can the Greek stock exchange be opened at this point, it's going to be a complete massacre...

It did not open today....

DeleteThis is a complex argument which I will admit upfront I do not have the competence to understand. However, since I have been following the news of Greece closely over the last six months, it seems to me that everything was hiding in plain sight. If one listened to the rhetoric of Jeroen Djisselbloem from the moment the ECB began to pressure Greece, Djisselbloem was constantly being quoted in the media, either with attriibution or via transparent leak, that a "Cyprus-style" bail in was in the cards for Greece. This seemed plainly designed to accelerate the ongoing slow motion bank run, since it is impossible to believe Djisselbloem would not be aware of the impact of his words.

ReplyDelete"The remaining uninsured deposits - about 30% of the deposit base - are mainly the working capital of Greek businesses" -- doesn't compute, ECB website says 13B of corporate deposits as of 2015-05, probably <10B by now, and some of this is likely <100K protected, so this is much smaller than 30% of the deposit base. I would guess it's mostly rich grannies who don't read zerohedge. Where does the 30% number come from anyway?

ReplyDelete"The creditors are in no mood to cut Greece any slack" -- the creditors aren't a uniform self-consistent bunch. The Finnish finance minister is not the one who will do the bank resolutions. From a reasonable insolvency practitioner point of view, it makes no sense to nuke the tiny working capital of the businesses who owe you long term loans (doom loop: a bail-in will cause further impairment to the loan book. wasn't so circular in Cyprus). Besides once the banks are ESM-owned, any trick to feed them some money may not be monetary financing of (national) governments anymore, so the toolset may be more flexible.

Also a point to note is that internal capital flight is still allowed (e.g. prepay taxes or loans, use poorer family members' unused insured deposit allowance, split between multiple Greek banks, etc) which is not very consistent with a planned(!) bail-in.

You obviously aren't aware that a new decree bans people from using existing deposits to repay loans at the same bank. I'd say that is setting the scene for a bail-in.

DeleteThe 30% figure is a ballpark estimate from a number of sources. It does need to be checked. However, ECB's figure for corporate deposits seems low to me. I'd guess they have not treated microbusiness deposits as "corporate". In Greece this would seriously understate business deposits.

Frances,

ReplyDeleteJust to point out that the main factor on the Q4 recession was caused by the possibility of Syriza coming to power in Q1. Markets and a sizable part of the Greek people were already fearing what a Syriza government would be and there were already a reduction in deposits.

Greece voted in the worst possible government for them, they were not competent enough to develop and push a plan to get the country of the Euro, and they couldn't push the structural reforms this country sorely needs. Basically the moment the Greeks elected Syriza they voted for their society implosion, so I think the net result of getting a Troika-mandated government is still a win compared to what Syriza would if pushed out of the Euro without a plan.

Euro-friendly goverments, FAILED

DeleteIMF-ECB-EU's proposals FAILED

SYRIZA's problem was the ultimatum: Either you vote whatever we tell you, or you will be the first govenment that will face deposit's ...haircut (not to mention other severe measures against Greece)

EU was the worst solution for countries like Greece AND is trapped in

Actually the rot set in in September 2014 when Samaras said Greece could leave the bailout program early: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/09/23/uk-eurozone-greece-germany-idUKKCN0HI1AD20140923

DeleteInvestors got cold feet at the prospect of Greek govt not being supervised. Bond yields rose from October onwards. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/charts/greece-government-bond-yield.png?s=gggb10yr&d1=20140101&d2=20151231

I agree things got much worse when it became evident Syriza would win the election, but that was not the cause of the Q4 2014 downturn.

"Just to" point out that the main factor on the Q4 recession was caused by the possibility of Syriza coming to power in Q1"

ReplyDeleteRubbish supply side explanation.

The recession was mainly because the summer was over and austerity remained. Most of the few jobs created were eliminated by the seasonal tourism end of temporary contracts. Also exports were lower because of the deflation in Europe, especially in agriculture and some industrial items. Demand side was the issue in Q4(not just in Greece but Europe)

Very good post trying to explain what would actually happen.

ReplyDeleteIt seems that the threat of bail-in of depositors to the banking system is enough to cause a bank run. It is clear that even discussions of that will get everybody to think about the money in their banks and move it.

I was clearly under the impression that bail-in was a one-off in Cyprus, trying to get at money-laundering Russians. Now, all of a sudden, it is official policy.

I know what I would do if I had money in an account in Spain, or Italy now. Move it as quickly as I can to Germany or Switzerland.

It just shows that people trying to deal with the crisis are completely struggling. What they propose will make it worse.

I was clearly under the impression that bail-in was a one-off in Cyprus, trying to get at money-laundering Russians. Now, all of a sudden, it is official policy.

DeleteDon't you believe it. Read this link which shows that it was not Russian or even British ex-pat money that caused the crisis in Cyprus. It was our old friends, the large, well-connected Eurozone banks.

"The more I look at it, the less benign this bailout deal appears. Indeed it looks to me as if it was set up to do considerable damage to the Greek economy"

ReplyDeleteExactly, who want to be bullied by Regling (ESM) after being bullied by Draghi (ECB). They are not credible as liquidity providers, running their institutions as debt collection agencies.

So other alternatives are available:

https://radicaleconomicthought.wordpress.com/2015/07/20/bank-rescue-advice-to-greece-follow-the-germans/

(1) run your own bad bank

(2) get ECB to deal with bad debts

(3) get ECB funding for insolvent banks

All three solutions do not need another 25bn, and should therefore be preferred by the Greeks.

Yes, but they unfortunately require the ECB to cooperate. Not at all clear that it would do so.

DeleteAs I read your post, I found myself needing to learn more about the BRRD ( Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive). I soon came to the conclusion that the BRRD contemplates individual bank structures that might fail, not entire central bank failure of one member nation. Would you agree that the BRRD is not correctly structured for the Greek situation where the entire nation is suffering national bankruptcy?

ReplyDeleteI find myself forced to consider that the Greek nation is much better described as a company-structure rather than a national-structure. Of course the big difference between the two descriptive structures is that nations can print their own currency but companies can not.

If we think of the Greek nation as a company, we find that the Greek business model results in more money leaving the model than is brought in. Loans have filled the gap for years. Now the lender has decided that the Greek national company is bankrupt. Greece has a problem. The lenders have a problem. The people of Greece have a problem.

It seems to me that Greece, whether considered as a nation or a company, needs a new business plan. The new business plan must balance money flows between Greece and all foreign trading partners. The new business plan would be very similar to the new business plan that comes out of a bankruptcy settlement.

If we follow the line of thinking outlined here, we would need to see the BRRD enhanced with a national bankruptcy provision. There needs to be a procedure to aid and repair countries that have been declared bankrupt by their trading partners.

Frances,

ReplyDeleteyou said "Greece's banks have suffered a continual deposit drain since the beginning of the year. This is how they became dependent on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) funding from the Bank of Greece."

If my memory is fresh enough, starting ELA was the consequence of a conversation between Draghi and Varoufakis. After that, the ECB decided to stop funding Greek banks, and the only option was ELA...

Regards

Well, there are two issues here. Firstly, because of deposit flight from December 2014 onwards Greek banks needed far more liquidity. It's this that I was referring to. However, I have conflated ECB funding with ELA. Up to the end of February, Greek banks were able to obtain the additional liquidity they needed from the ECB. At the end of February, however, because of uncertainty over the future of Greece's bailout programme, the ECB revoked access to funding for Greek banks, forcing them to use ELA funding from the Bank of Greece, which is more expensive. But even ELA is subject to ECB control, and ECB capped it on 28th June. Hence the bank closures and capital controls.

DeleteHowever much Schäuble and Merkel want to dress it up, they have used the HFSF, EFSF and ESM to move all exposure by banks to Greece (whether by German, French or Greek banks) onto the shoulders of European taxpayers, particularly German taxpayers. Why the German taxpayers admire Dr Schäuble, defies logic. Deutsche bank is reputed to have a €60 trillion exposure to forex derivatives. Deutsche only have €2 trillion in CDS default insurance. The two CEOs of Deutsche Bank were fired a few weeks ago, hinting at the huge problems besetting the German bank. Schäuble and Merkel find themselves in a terrible bind - a bind which Tsipras and Varoufakis tried to exploit.

ReplyDeleteThe Greeks actually need to exit the Euro to prevent contagion by the German banks.

I believe that the bail in will probably occur within 2015,have no idea if ESM will step in much later.

ReplyDeleteAlso, its possible to see deposits under 100.000€ to get hit by a small percentage

But for the moment,Tsipras is struggling to keep his government together,snap elections can be called anytime and that could jeopardize any schedule

All this and not a mention of the systemic failure of the Eurozone and the complicity of banks and bribes that got Greece to join Euro in the first place. Nothing about the democratic will of the people. Capitalism is failing and economics whether Classical or Neo-Classical don't have the answers. Sooner or later the bubbles will explode, there is no blueprint for transition, the future in the present situation is pretty bleak...

ReplyDelete