A dent in the surface of time

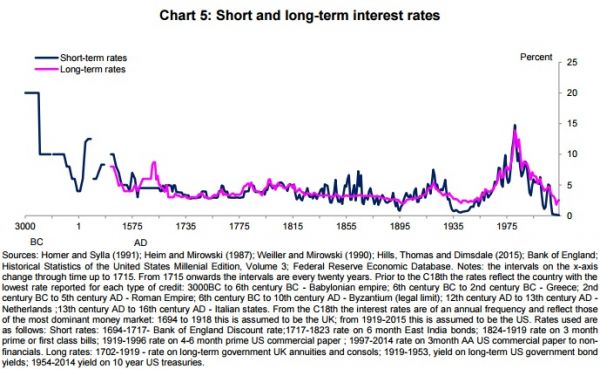

This chart has been fascinating me for ages. It was produced by the Bank of England to illustrate a speech by Andy Haldane. Shock, horror - we have the lowest interest rates for 5,000 years. Even in the Great Depression they were higher than they are now.

Note also the divergence of long-term and short-term interest rates. This is encouraging, since it suggests that investors view future prospects as brighter, though hardly scintillating. Central banks have been trying to close that gap with various monetary policy tools, the idea being to bring forward some of that future enthusiasm into the present day. But so far, all they have succeeded in doing is depressing expected interest rates far into the future.

Now, policy makers are beginning to talk about interest rates remaining permanently lower than their long-run average. Here, for example, is John Williams of the San Francisco Federal Reserve discussing expectations for r*, the rate of interest when the economy is at full capacity:

A variety of economic factors have pushed natural interest rates very low and they appear poised to stay that way (Williams 2015b, Laubach and Williams 2015, Hamilton et al. 2015, Kiley 2015, Lubik and Matthes 2015). This is the case not just for the United States but for other advanced economies as well. Figure 1 shows estimates of the inflation-adjusted natural rate for four major economies: the United States, Canada, the euro area, and the United Kingdom (Holston, Laubach, and Williams 2016). In 1990, estimates ranged from about 2½ to 3½%. By 2007, on the eve of the global financial crisis, these had all declined to between 2 and 2½%. By 2015, all four estimates had dropped sharply, to 1½% for Canada and the United Kingdom, nearly zero for the United States, and below zero for the euro area.And here is Williams's Figure 1 showing how rates have fallen:

Unlike the Bank of England's chart, these are real interest rates. But they show the same thing - except that Williams has told only half the story.

It is all about the start point. This chart (courtesy of Economics Help) shows UK nominal interest rates, as in the Bank of England's chart, but plotted against inflation:

The real interest rate is the nominal rate minus inflation. So we can see that in 1975, when the nominal interest rate was about 12% and inflation spiked to 25%, the real interest rate was deeply negative. But by 1981, nominal interest rates had risen to 17%, and the real interest rate was positive. It remained positive for the next 25 years. Remarkably so, in fact. The period from 1982 to 2007 had the highest real interest rates since WWII.

Perhaps even more importantly, for much of that period nominal rates were very high too. People take far more notice of nominal rates than they do real ones. Money illusion is definitely a thing, when you are paying a mortgage and saving for your retirement. And the Bank of England's chart shows that the period from 1975 to maybe 1995 had the highest nominal rates in recorded history. Not since Babylon had there been such high nominal rates sustained for so long.

So the young adults of the 1980s paid the highest interest rates in history on their mortgages and car loans. Now, they are approaching retirement - indeed the oldest among them have already retired. And today's ultra-low interest rates seem like a major betrayal. Where have the returns on their savings gone?

This is a bigger problem than it might seem. In the 1980s, companies started to replace defined-benefit pensions, which promised an income based on final salary, with defined-contribution pensions, where the returns on investment provide an income in retirement. By the mid-1990s, most defined-benefit schemes were closed to new entrants.

Replacing defined-benefit with defined-contribution didn't seem that big a deal at the time. Some people even thought it was better. After all, with the rates prevailing at the time, you wouldn't need a huge investment portfolio to generate quite a decent income in retirement. It never occurred to anyone that interest rates would fall.

And yet they were already falling. All three charts show that interest rates have fallen steadily since their 1980 peak. In fact John Williams's chart shows that real interest rates have fallen rather less in the UK than elsewhere: but it is nominal interest rates that people understand. Now, people are not going to get anything like the returns on their pension investments that they expected. Nor on any other form of savings, either. If anything, private pensions and life insurance schemes look even worse than defined-contribution corporate schemes, and the interest rates on liquid savings such as ISAs are approaching zero.

Over at Bond Vigilantes, Jim Leaviss has an excellent explanation of the rise and fall of post-war interest rates. I have shamelessly borrowed his charts. This one wonderfully shows how the anomalously high interest rates of the 1980s and 90s were entirely due to the baby boom:

And here is Jim's verbal explanation:

The relatively low supply of labour in the 1970s gave power to those of working age. Trade union membership peaked in the late 1970s (when 12 million people in the UK were members) and wage growth outstripped productivity growth and inflation. Government debt burdens grew, and interest rates and bond yields hit double digits. There were talks of ‘buyers’ strikes’ by institutional gilt investors in the UK.

But as the baby-boomers entered the workforce after school or college, there was a significant improvement in the demographic trends. From that low of 40% in 1975, by the end of the 1980s the ratio of workers to non-workers was back above 50%, peaking at over 60% by the end of the 20th century. The developed world had become a world with lots of workers, keeping inflation low (trade union membership shrank), producing tax revenue to reduce government borrowing (at times in the US there was even discussion about retiring the national debt), and investing in paper assets like government bonds to provide future incomes in retirement. Inflation collapsed (you could argue that central banks, despite becoming fierce inflation fighters over this period, starting with Paul Volker taking over at the US Federal Reserve in late 1979, should take little credit here; the demographics did the heavy lifting) and 10-year US Treasury bond yields halved from nearly 13% at the start of the 1980s to 6.5% by the end of the 1990s.Now the baby boomers are leaving the workforce, we should expect interest rates to rise. Here is Jim's view of where interest rates should be now:

So perhaps the baby boomers were not unreasonable in expecting their investments of the 1980s and 90s to deliver a comfortable retirement. Something has gone badly wrong. But what?

Jim identifies five reasons why interest rates have failed to recover. To many people, they will be all too familiar.

- Globalisation: offshoring of jobs to cheaper locations and competition from cheaper imports, putting downwards pressure on wages and prices. In the UK, this was compounded by immigration from the EU.

- The Great Financial Crisis of 2008: deliberate cuts in interest rates, interventionist central banks preventing buyers' strikes, financial repression and poor wage growth

- Technology: progressive replacement of humans with robots causes wages and prices to fall

- Longevity and under-saving: people are living longer, and as already mentioned, older workers have not saved enough, so they are staying in the workforce for longer

- China's influence on the US Treasury bond yield (which influences all other government bond yields)

As Jim says, "the simplicity of demographic models was attractive, but what worked in a closed economy failed in a connected world".

For young people, today's low interest rates mean that they have to save much more and take more investment risk to achieve the sort of income in retirement that the post-war generation had. But those who were young adults in the 1980s and 90s don't have enough of their working lives left to build up the size of pension pot now needed to generate a comfortable retirement income. They are looking at a much less prosperous retirement than they expected.

I suspect that the bleaker future facing Britain's older working-age people might help to explain why a high proportion of them self-identify as "have nots", according to a recent survey by Britain Thinks (bottom LH quadrant):

This might go some way towards answering Rick's question - "why are baby boomers so angry"?Younger boomers - those now aged 50-64 - have reason to be angry, as indeed do their 40-something brothers and sisters. Their wages have been stagnant for a decade, their occupational pensions are stuffed and their state pensions are receding into the distance. They are frightened of cuts to the healthcare they will need in retirement and worried that they may have to sell their houses to pay for their care. Many of them blame their precarious financial situation on globalisation, immigration and bankers. And if Jim is right, they have a point.

So they want to shut the doors, cut the trade ties, kill the parasite financial services industry and jail the bankers. Then they can have their high interest rates back. After all, they paid those rates on their mortgages. Now they expect to receive them on their savings. It's only fair.

And they paid in for their pensions and their healthcare, too. So close the tax loopholes, make the rich pay their fair share and honour the pensions and universal healthcare promises of the past. It's only fair.

And they paid in for their pensions and their healthcare, too. So close the tax loopholes, make the rich pay their fair share and honour the pensions and universal healthcare promises of the past. It's only fair.

There are an awful lot of the baby boomers, and they vote. What they regard as "fair" will dominate political debate for quite a while to come. Resurgent populism now woos the old, not the young.

This leaves me with two unanswered questions. Firstly, why did people fail to see that the high interest rates of the 1980s and 1990s were anomalous? And secondly, why do Williams and others think low interest rates are here to stay? After all, if people in the 1980s could erroneously believe that high interest rates would last forever, people in 2016 can equally wrongly think that low interest rates are here to stay.

We are short-lived creatures: what seems "normal" to us may simply be a pimple or a dent on the surface of time. Looked at through the lens of 5000 years, the high interest rates of the 1980s and 90s were indeed a pimple, but those who lived through that time did not see it. Looked at through the same lens, today's ultra-low rates look suspiciously like a dent.

As we near the end of the golden age of globalisation, the emerging future looks to be nationalist and protectionist. The world is shrinking, becoming poorer and less connected. We may yet see the return of higher interest rates. If, that is, we don't blow the place up first.

This post has been focused on the UK, but many of the drivers I describe apply equally to other developed nations. Falling interest rates and a sense of betrayal among older people are features of much of the developed world. They are not unique to the UK, despite its unusual occupational pension system.

Related reading.

Thank you for this excellent article.

ReplyDeleteGreat graph.

ReplyDeleteSense sovereigns are running this their show, I have a few questions.

ReplyDelete1. Why would they want low interest rates?

2. Why would they want people and companies in debt? What's it to them?

3. Is all this private borrowing a reaction to money printing. If it is a loss over time to save and a gain to borrow, are people, companies, and finance acting on it?

But, given that prices of assets, and things are actually going up. If more than than stated, are sovereigns talking about low interest and low inflation a misdirection from actual price increases?

Taxes are very high, maybe high enough for sovereigns to actually be running surpluses. Could many be running surpluses but saying other wise and buying stocks and bonds?

Or, if many of the sovereigns are taxing high, borrowing at negative real interest rates, spending high, buying assets do we have a huge crowding out effect?

I really do not know what is actually going on. It is confusing.

I have seen a large run up in grocery prices. Looks like more than or equal to 5-7% per year. I read Greenspan mentioned stagflation recently. I remember that in the 1970s U.S. Is that what is going on?

If the price increases are due to a big credit bubble, oh boy. What then?

(In the 1970s stagflation the silver coins left circulation, and dollars could not be redeemed for gold by other sovereigns.)

What happened after stagflation, the US raised interest rates near 1980 in an attempt to end the 1970s stagflation.

"1. Why would they want low interest rates?"

DeleteBecause recession. After monetary action became the only game in town, base rates have come down sequentially with each recession. Low bond rates have been the next step, supposedly to "encourage" money into other parts of the economy to boost activity.

"2. Why would they want people and companies in debt?"

Because recession. In the absence of fiscal action, the only way to boost the economy is to push people into debt.

"Taxes are very high ..."

Really?

"Globalisation: offshoring of jobs to cheaper locations and competition from cheaper imports, putting downwards pressure on wages and prices. In the UK, this was compounded by immigration from the EU."

ReplyDeleteHeresy!

Aside from that, Japan has the same problems we have yet their interest rates are totally flat and have been for what, two decades?

Those boomers who could afford to buy property at the then prevailing high interest rates also benefited from high inflation effectively diminishing their debt.

ReplyDeleteLow interest rates are politically popular, especially in debt fired consumerist economies propped up by fake money from QE. We could all soon get a nasty pain in the equilibrium.

ReplyDeleteIndeed...

DeleteGeorge Osborne: «A credible fiscal plan allows you to have a looser monetary policy than would otherwise be the case. My approach is to be fiscally conservative but monetarily active.»

D Cameron: «It is hard to overstate the fundamental importance of low interest rates for an economy as indebted as ours… …and the unthinkable damage that a sharp rise in interest rates would do. When you’ve got a mountain of private sector debt, built up during the boom… …low interest rates mean indebted businesses and families don’t have to spend every spare pound just paying their interest bills. In this way, low interest rates mean more money to spare to invest for the future. A sharp rise in interest rates – as has happened in other countries which lost the world’s confidence – would put all this at risk… …with more businesses going bust and more families losing their homes.»

None of this seams very surprising to me. Indeed my head is hurting from banging against the wall while shouting "of course". Can we please include in the discussion the extraordinary growth in productivity in manufacturing and agriculture?

ReplyDeleteMy grandad told me that cost-price to retail margins in his department store in the 50s were around 5%. You added 5% to the cost price. Now, from what you can glean in a lot of sectors, cost price is 5% of retail price. Corporate shills will tell you that the incredible rise in margins for distribution represent "onshore value added", in design, advertising etc. I see just sticky prices, money pissed against the wall through an assortment of parasitic industries, avaricious bosses and offshore tax scams, and a huge potential for deflation. We're in an era of protecting your market share while you can, cashing in your chips when you can't. Who would invest? In the torrent of ideology that pours out of employer groups, I've yet to spot the recognition that their collective interest (in a strong national market, ie secure well paid employees) is different from their individual interests (in cheap labour). That the crunch arrives through retirement incomes shouldn't be surprising. We can always put off worrying about tomorrow.

In France, retirement income is still seen as a present-time obligation of the currently working to the currently retired. Perhaps this very old and basic formula will not look so silly in the future. Sorry for ranting. One day I'll tell you what I really think. I'm off to have a beer with Philip Green.

Private-sector pension plans are assets that central banks ought seriously consider buying as a form of QE.

ReplyDeleteRight now companies must pay relatively large amounts per job to their pension plans, as interest rates are so low, and companies expect them to remain low: lower than the central banks' targets in most western economies. Furthermore, due to low rates, and people living longer, company pension plans are often technically underfunded, leading to more investment by companies into pensions, rather than investments in other, perhaps more productive, users. This is especially the case with defined benefit plans.

The present expected value companies place on their plans in the "real world" would be lower than a central bank would place on those same plans, assume the central banks own interest rate targets are met. Central banks should offer to buy shares in company pension plans at a price premium to the companies' valuations: a midpoint perhaps, between companies' real valuations and expected valuation the CB would calculate assuming their own inflation targets were met.

Low interest rates are tied to the too much debt problem. In the UK's situation the 'too much debt' is not UK debt, but debt in exporting countries, especially China. The real value of the money we pay for our imports is declining,even without devaluation, but this cost is carried by Chinese workers and firms, who now need to increase productivity to stand still rather than to grow. Once China has its over due debt crisis, everyone else can complete their debt crisis too and when the dust settles interest rates will pick up and go positive again. Do we have any genius economists who can tell us what we need to do to make the global money system fit for purpose so this doesn't happen again?

ReplyDeleteI really enjoy this blog and have a lot of respect for the author.

ReplyDeleteOne tiny bit that I don’t understand:

“Note also the divergence of long-term and short-term interest rates. This is encouraging, since it suggests that investors view future prospects as brighter, though hardly scintillating.”

Is some other explanation possible, like investors chasing bigger returns, or just taking a bigger risk (we never know what future holds), or if they are repaying debt just trying to stay afloat?

As a matter of fact, if future is bright, then the investors should buy short term, thus losing a bit of the rate, but then profit on the expected higher return in the future?

Anyone?

Thanks, and kind regards to the author.

Jim Leaviss offers 5 reasons for the breakdown of his long-dated gilt model in the noughties.

ReplyDeleteWhat would the model predict were it adjusted for the absence of the “credit impulse” following the GFC?

The most likely reason that the model broke down is that the relationship was not causal.

DeleteThere is a lot of interesting story and data here but there are some aspects that are really disagreeable, and mostly to do with interest rates and pensions.

ReplyDeleteThe first thing is that low nominal interest rates have disappointed only those boomers who have gone long cash; those who have invested in property in the south east and in shares and long term bonds have seen fantastic profits from the fall in interest rates. Property in the south east has been returning 100% profits on cash invested for decades, thanks to government-sponsored leverage. Plus low interest rates and government sponsored leverage have pushed stocks higher too.

Plus as to south-east property, every time it doubles in price, the current owner gets in effect the property free, as a the CEO of a mortgage lender pointed out a while ago. For example those who bought a £100,000 property in 2001 with a £10,000 deposit, and saw its price zoom to £200,000 in 2011 got the £90,000 mortgage paid back by the £100,000 capital gain, plus a £10,000 extra profit. Property in the south-east has doubled in price at least twice since 1980.

So if people suffered from low interest rates because they stayed long cash it was entirely their problem, because in a thatcherite model people who make investment mistakes lose.

The other big problem is that the switch from "final salary" (DB) company pension funds to "money purchase" (DC) individual pension funds did not just pass investment performance volatility from the company to the individual, which was a relatively small deal.

The big deal was that contributions to "money purchase" individual funds are usually one third (10% of headline wage instead of 30%) of those that were made to "final salary" company funds, and thus (but for volatility) they will result in pension that are on average 1/3 of those from defined benefit funds. That before any consideration of impact of low interest rates on those who went long cash or long property/shares.

The other point is that there are attempts to reproduce the demographic boom of the 1970s by high levels of immigration of large numbers of young, cheap workers from eastern Europe (and after Brexit from third world countries as "temporary indentured servants").

Frances,

ReplyDeleteI seriously doubt that the relationship between demographics and gilt yields was causal.

«doubt that the relationship between demographics and gilt yields was causal»

DeleteWell, scottish oil exports also helped quite a bit. But asset prices are influenced by demographics, just like GDP is; for example there is a good argument that stock prices are driven by the ratio of middle aged to younger workers:

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2010/04/demographics-and-stock-market-fluctuations.html

Low nominal interest rates have disappointed only those boomers who have gone long cash; those who have invested in property in the south east and in shares and long term bonds have seen fantastic profits from the fall in interest rates. Property in the south east has been returning 100% profits on cash invested for decades, thanks to government-sponsored leverage. Plus low interest rates and government sponsored leverage have pushed stocks higher too. So if people suffered from low interest rates because they stayed long cash it was entirely their problem in a thatcherite approach, which they no doubt endorsed.

ReplyDeletePlus the switch from "final salary" (DB) company pension funds to "money purchase" (DC) individual pension funds did not just pass investment performance volatility from the company to the individual, which was a relatively small deal: contributions to "money purchase" individual funds are usually one third (8-10% of headline wage instead of 25-30%) of those that were made to "final salary" company funds, and thus (but for volatility) they will result in pension that are on average 1/3 of those from defined benefit funds. That before any consideration of impact of low interest rates on those who went long cash or long property/shares.

Another point is that there are attempts to reproduce the demographic boom of the 1970s by high levels of immigration of large numbers of young, cheap workers from eastern Europe (and after Brexit from third world countries as "temporary indentured servants").