Despair deaths and regional inequality

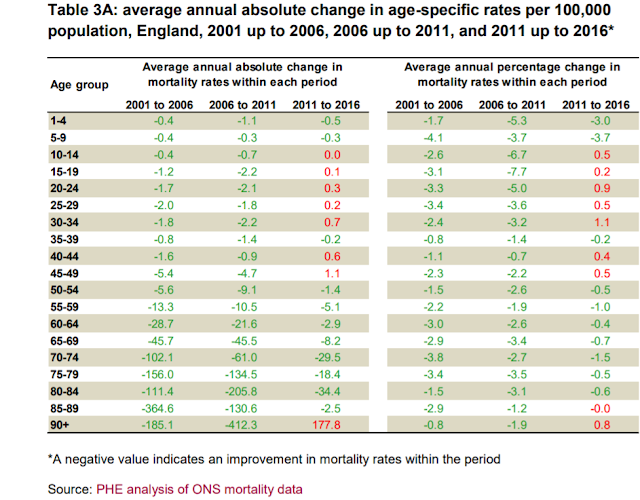

I can't stop looking at this table. Mortality rates in England rose between 2011-16 for teenagers and most working-age adults under 50:

That's bad enough. But what should give all of us pause is the reason that Public Health England (PHE) gives for rising mortality among young and middle-aged adults:

This helpful chart from ONS shows the change in drug-related deaths in England and Wales since 1993:

Drug-related deaths, which had been falling for both sexes since 1999, increased sharply from 2012 onwards, particularly among men. Most of these deaths were "accidental poisonings", though 17% of male drug-related deaths and 34% of female deaths were suicides. Unlike the US, the rise in accidental poisonings does not seem to be related to opiate abuse. ONS's breakdown of the figures shows that opiate deaths (except codeine) have remained steady or even fallen, but there are rising deaths across most classes of non-opiates, including fentanyl (which is however frequently cut with heroin), anti-depressants and anti-psychotics, and above all cocaine.

Approximately two-thirds of drug-related deaths are due to "drug misuse," which the NHS formally defines as "the continued misuse of any mind-altering substance that severely affects a person’s physical and mental health, social situation and responsibilities." The figure is higher for men than for women: 71% of male drug-related deaths are due to misuse. It is also sharply divided by region, with the North East having the highest rate of death due to drug misuse, and London the lowest:

It is hard not to see this as related to poverty and inequality. Deaths due to drug misuse are much lower in the prosperous south east of England than in poorer regions.

The previous graphics do not include deaths due to alcohol poisoning. The following charts, however, do include alcohol-related deaths.

The rise in cases of accidental poisoning, including from alcohol, among men and women aged 40-49 is clearly shown on this pair of charts from ONS. The left-hand chart also shows a rise in male suicide since 2010. Taken together, suicide and accidental poisoning are now by far the biggest cause of premature death among middle-aged men, though this is partly due to rapidly falling rates of death from heart disease.

The picture is significantly worse for 20-39 year olds, both men and women:

Accidental poisoning and suicide have risen for both sexes, but particularly for men.

These charts paint a worse picture than the PHE figures. Accidental poisonings have been rising since the mid-2000s for both sexes, but until 2010 this was masked by falling death rates from other causes, particularly traffic accidents and heart disease. In particular, the sharp fall in road deaths for young men no doubt made a significant difference to the earlier PHE figures. Why did it level off from 2010 onwards, when road death rates for young women continued to fall?

Perhaps most worrying of all is the ONS's comment (there is no chart) about rising suicide rates among adolescents:

Of course, these figures are for England and Wales only. But Scotland too seems to have a "despair deaths" problem: the ONS says that there was an 8% rise in drug-related deaths between 2016 and 2017, albeit from a low number (less than a thousand deaths). In Northern Ireland, however, the trend is in the opposite direction. Drug-related deaths fell by 13% between 2015 and 2016, the latest figures available. Northern Ireland's economy has grown fast since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998: although parts of the region remain very poor, per capita GDP is now higher than in Wales and in the North East of England. Perhaps this helps to explain the reverse trend in Northern Ireland.

Looking beyond British shores, the ONS says that the drug-induced deaths rate (for those aged 15 to 64 years) for the EU, Turkey and Norway was less than a third of the rate in England and Wales. And this brings me to my final chart. Here is Eurostat's comparative presentation of regional inequality in the 28 countries making up the EU:

Just look which country stands out. No doubt some will say this has nothing to do with the UK's much higher rate of drug-related deaths. Correlation doesn't indicate causation, and all that jazz. I don't believe it. But perhaps the IFS can sort this out. It is just embarking on a five-year study into inequality and its effects, to be chaired by the economist Angus Deaton, co-author of groundbreaking studies into "despair deaths" in the USA.

Many blame the turn to austerity in 2010 for the disturbing trend towards drug and alcohol misuse and suicide among young and middle-aged people in England and Wales. Others blame the legacy of Thatcher, the deindustrialisation of the North and the continuing poverty of communities devastated by the closure of facturies and mines. But although all of these factors could be significant, the charts don't wholly support either interpretation. Accidental poisonings started to rise for men in about 2002, and for women in the mid-2000s. Clearly, there was some kind of change then, and I think we need to know what it was. My money would be on easy availability of drugs via the internet. But if anyone has other ideas - preferably with supporting evidence - please do say. Comments are open. Let's get this discussion moving.

Related reading:

Inequalities in the twenty-first century: introducing the IFS Deaton review - IFS

Left behind: can anyone save the towns the economy forgot? - FT

Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century - Case & Deaton

That's bad enough. But what should give all of us pause is the reason that Public Health England (PHE) gives for rising mortality among young and middle-aged adults:

Among people aged 20-44, an increase in mortality rates from accidental poisoning had a negative effect on life expectancy between 2011 and 2016 of -0.06 years in males and -0.11 years in females....

Data from ONS indicate that in this age group, over the whole period from 2011 to 2016, 70% of accidental poisonings were due to drug misuse and 10% were to alcohol.PHE also notes a slight increase in male mortality rates due to cirrhosis, which is in the top 10 causes of death for men. Among women, suicide is playing a slightly larger role:

An increase in the female suicide rate in the 20-44 age group also had a small negative effect on life expectancy between 2011 and 2016 (-0.02 years)."(These figures are for England only.)

This helpful chart from ONS shows the change in drug-related deaths in England and Wales since 1993:

Drug-related deaths, which had been falling for both sexes since 1999, increased sharply from 2012 onwards, particularly among men. Most of these deaths were "accidental poisonings", though 17% of male drug-related deaths and 34% of female deaths were suicides. Unlike the US, the rise in accidental poisonings does not seem to be related to opiate abuse. ONS's breakdown of the figures shows that opiate deaths (except codeine) have remained steady or even fallen, but there are rising deaths across most classes of non-opiates, including fentanyl (which is however frequently cut with heroin), anti-depressants and anti-psychotics, and above all cocaine.

Approximately two-thirds of drug-related deaths are due to "drug misuse," which the NHS formally defines as "the continued misuse of any mind-altering substance that severely affects a person’s physical and mental health, social situation and responsibilities." The figure is higher for men than for women: 71% of male drug-related deaths are due to misuse. It is also sharply divided by region, with the North East having the highest rate of death due to drug misuse, and London the lowest:

It is hard not to see this as related to poverty and inequality. Deaths due to drug misuse are much lower in the prosperous south east of England than in poorer regions.

The previous graphics do not include deaths due to alcohol poisoning. The following charts, however, do include alcohol-related deaths.

The rise in cases of accidental poisoning, including from alcohol, among men and women aged 40-49 is clearly shown on this pair of charts from ONS. The left-hand chart also shows a rise in male suicide since 2010. Taken together, suicide and accidental poisoning are now by far the biggest cause of premature death among middle-aged men, though this is partly due to rapidly falling rates of death from heart disease.

The picture is significantly worse for 20-39 year olds, both men and women:

Accidental poisoning and suicide have risen for both sexes, but particularly for men.

These charts paint a worse picture than the PHE figures. Accidental poisonings have been rising since the mid-2000s for both sexes, but until 2010 this was masked by falling death rates from other causes, particularly traffic accidents and heart disease. In particular, the sharp fall in road deaths for young men no doubt made a significant difference to the earlier PHE figures. Why did it level off from 2010 onwards, when road death rates for young women continued to fall?

Perhaps most worrying of all is the ONS's comment (there is no chart) about rising suicide rates among adolescents:

For boys and girls aged 5 to 19 years, suicide and injury or poisoning of undetermined intent remained the leading cause of death in 2017, accounting for an increased proportion of deaths at this age, compared with the previous year. The increase in deaths due to this cause was especially notable for females, accounting for 13.3% of deaths at this age, compared with only 9.6% in 2016. In England and Wales, a conclusion of suicide cannot be returned for children under the age of 10 years.Despair can take hold at any age.

Of course, these figures are for England and Wales only. But Scotland too seems to have a "despair deaths" problem: the ONS says that there was an 8% rise in drug-related deaths between 2016 and 2017, albeit from a low number (less than a thousand deaths). In Northern Ireland, however, the trend is in the opposite direction. Drug-related deaths fell by 13% between 2015 and 2016, the latest figures available. Northern Ireland's economy has grown fast since the Good Friday Agreement of 1998: although parts of the region remain very poor, per capita GDP is now higher than in Wales and in the North East of England. Perhaps this helps to explain the reverse trend in Northern Ireland.

Looking beyond British shores, the ONS says that the drug-induced deaths rate (for those aged 15 to 64 years) for the EU, Turkey and Norway was less than a third of the rate in England and Wales. And this brings me to my final chart. Here is Eurostat's comparative presentation of regional inequality in the 28 countries making up the EU:

Just look which country stands out. No doubt some will say this has nothing to do with the UK's much higher rate of drug-related deaths. Correlation doesn't indicate causation, and all that jazz. I don't believe it. But perhaps the IFS can sort this out. It is just embarking on a five-year study into inequality and its effects, to be chaired by the economist Angus Deaton, co-author of groundbreaking studies into "despair deaths" in the USA.

Many blame the turn to austerity in 2010 for the disturbing trend towards drug and alcohol misuse and suicide among young and middle-aged people in England and Wales. Others blame the legacy of Thatcher, the deindustrialisation of the North and the continuing poverty of communities devastated by the closure of facturies and mines. But although all of these factors could be significant, the charts don't wholly support either interpretation. Accidental poisonings started to rise for men in about 2002, and for women in the mid-2000s. Clearly, there was some kind of change then, and I think we need to know what it was. My money would be on easy availability of drugs via the internet. But if anyone has other ideas - preferably with supporting evidence - please do say. Comments are open. Let's get this discussion moving.

Related reading:

Inequalities in the twenty-first century: introducing the IFS Deaton review - IFS

Left behind: can anyone save the towns the economy forgot? - FT

Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century - Case & Deaton

I dont know about buying over the internet, but in the small seaside town on the south coast where I live , I see drugs being sold on the streets most days. It is rare to see any police. Drug addiction & street homelessness are closely linked here. Recent prosecutions show people from London selling here & along the coast, renting or staying in flats locally. I don't think the police have enough resources to stop this, & in fact I personally believe we would do better to follow Portugal's example & decriminalise drug use. You can see from Portugal's position in the table above, that their death rates have decreased.

ReplyDeleteI think this is probably correct. Not the internet, but just the more ready availability to a wider pop of drugs. A 'symptom' of this is the visibility of widespread use. Just use your nose in any public space and daily you encounter (strong) cannabis use.

DeleteWouldn't Uruguay's policy of nationalising the drugs trade be an even better one, as it breaks the link between drugs and criminals in a way that mere decriminalisation does not?

DeleteSell drugs in intentionally unglamorous government-run clinics, at a price just low enough to dissuade users from going back to illegal suppliers, and use the profits to fund treatment programmes for addicts (who consume over 50% of the drugs despite being less than 10% of the drug users) and perhaps also for other local government spending (since the clinics will almost certainly be in poor areas due to nimbyism).

Oh, those are grim figures.

ReplyDeleteNo evidence, but I would look into the ban on legal highs. Frances suggests easy availability of "drugs" on the internet may be a factor, but perhaps it's more the lack of alternatives. Ireland might be a useful comparison, since it went with the ban way back and comes second to the UK in that awful table.

Also outsourcing of mental health services to anti-professional corporations. What is it with English speakers that they torture themselves so?

For inequality to be the answer we need more information. As you say, a rise in recent years. Has regional inequality risen in recent years?

ReplyDeleteThe Gini for the country has fallen, as we know.

So?

well, as I said, Tim, we need more information. The regional distribution of deaths from drug misuse correlates strongly with relative regional poverty, but that doesn't explain why deaths from this cause rose from the early 2000s onwards: after all, the North East has been poverty-stricken since the 1980s. Nor do rising deaths from drug misuse necessarily indicate that regional inequality is rising. I hope the Deaton review looks at all of this.

Delete